For too long, writing education has faced a significant challenge: many children and young people not only underachieve in writing but also develop a strong dislike for it. Surveys from the National Literacy Trust have continually highlighted a decline in children’s enjoyment, volition, and motivation to write both in and out of school, with approximately three quarters expressing indifference or an active dislike for writing¹. This disengagement is closely linked to underachievement, with children who do not enjoy writing eight times more likely to perform below the expected level². This pervasive issue necessitates a re-evaluation of current teaching practices and a shift towards pedagogies that develop both proficiency and pleasure in writing.

Why Johnny can’t write: A lack of competency

Underachievement in writing is not solely a matter of motivation; it also stems from a lack of effective instructional practices that equip children with the necessary skills and processes to be capable in the broadest sense. It’s our belief that the current National Curriculum exacerbates this problem. It is simply not designed to nurture children so that they feel:

- Personally capable

- Socially connected and recognised

- Academically successful

It does not provide a clear framework for developing the full range of competencies young writers need. Below are just some of the reasons we believe Johnny can’t write.

1. A lack of explicit writing instruction

In the name of efficiency, many schemes amalgamate writing into reading lessons, under the mistaken belief that asking children to produce written responses to texts will naturally improve their writing. Writing about your reading is different to explicitly teaching it. This approach ignores a key truth: while reading instruction supports writing, and writing instruction supports reading, one cannot replace the other³. Research is clear — children need dedicated, explicit lessons that break down the skills, strategies, and processes involved in crafting texts⁴.

2. Rushing for quantity over quality

Many commercial schemes treat writing as a short, rigid, and linear sequence – prewriting, drafting, editing — all completed in quick succession. In this race to produce a high volume of work, guidance often skips or skims through essential stages such as idea generation, revision, and careful proofreading. The sorts of things that take children’s writing from adequate to great. Instead, children and teachers are pushed to churn out writing rapidly, rather than given the time to explore, refine, and develop their ideas.

This hurried approach forces inexperienced writers to juggle both composition (shaping thoughts, structuring ideas) and transcription (neat handwriting, perfect spelling, accurate punctuation) simultaneously. Such multitasking overloads their working memory, reducing the quality of both their thinking and their expression. Genius takes time. Yet the current emphasis on speed robs children of the chance to produce their very best writing.

3. SRSD instruction remains largely unknown to teachers

Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) is by far the most thoroughly researched and consistently effective approach to teaching writing⁵. It explicitly teaches students evidence-based strategies for generating ideas, planning, drafting, revising, and proof-reading, while also developing their ability to monitor and manage their own writing process. SRSD blends cognitive strategy instruction with self-regulation techniques, helping children not just to know what good writing involves, but how to do it for themselves.

Studies show that SRSD benefits struggling and proficient writers alike, improving both the quality and quantity of their writing. Despite its strong evidence base and adaptability across ages, genres, and abilities, SRSD remains virtually absent from most UK classrooms. Few teachers encounter it in their initial training, and fewer still receive professional development in how to implement it. As a result, one of the most effective tools for improving writing outcomes – and for giving children the confidence to see themselves as independent writers – remains unused in the very places where it is needed most.

4. Writing on topics they barely know or care about

The quickest, cheapest and easiest way to improve children’s writing proficiency is to support them in choosing their own writing topics. A major barrier to children’s writing success is being forced to write about topics they know little about (and often care even less for). When writing tasks draw on content outside their long-term memory, children are forced to work with ideas without a secure knowledge base to support them. This dramatically increases cognitive load: they must translate unfamiliar content while also managing the demanding processes of composition and transcription. The result is writing that feels both harder and less meaningful than it needs to be. Supporting children to choose their own writing topics provides a ready-made foundation of content knowledge and motivation, making the process of writing not only more successful but also far more rewarding.

5. Decontextualised grammar teaching

Formal grammar lessons taught in isolation, without direct connection to real writing, result in negative writing performance because there is no need for children to transfer what they learn to their actual compositions⁶.

6. Not studying mentor texts

Children are rarely given the chance to read and discuss the kind of texts they will later be asked to create. Too often, pupils are expected to produce a particular form of writing, such as a one-page short story, a persuasive letter, or an information text, without first seeing authentic examples of how real writers approach those very genres. This leaves them trying to imitate a form they have never meaningfully examined.

To become confident and independent writers, children need to read as writers⁷. This means engaging closely with mentor texts. These are texts which realistically match the type of writing they are being asked to craft for themselves. By analysing, discussing, and studying these exemplars, children begin to see how writers make choices about voice, organisation, and style. It shows children what’s possible and probable in concrete terms. Without this step, writing tasks become guesswork rather than craft work.

7. The DfE’s low expectations during teacher training

Many teachers enter the profession without the deep, practical knowledge of writing needed to teach it well⁸. This is partly because, during their own schooling, they missed out on the kind of writerly apprenticeship they deserved. Nationally, the problem is compounded by the absence of rhetoric or composition degrees, and by the fact that few teachers hold creative writing or journalism qualifications. Most are far more likely to have studied English literature. Yet being skilled in literary analysis is not the same as being a writer, nor does it prepare someone to teach the complex, iterative processes of writing.

The issue is further entrenched by the low expectations in the DfE’s Core Content Framework for Initial Teacher Education, which contains just one bullet point on the teaching of writing, and by Ofsted’s Initial Teacher Education Inspection Framework, which fails to mention writing at all (apart from checking secondary teachers’ handwriting). As a result, minimal time is devoted to effective writing pedagogy, leaving new teachers without the subject knowledge and pedagogical knowledge they need. This lack of preparation perpetuates ineffective classroom practices and deprives students of the opportunity to learn to write with skill and independence.

Why Johnny won’t write: A crisis in motivation

A primary reason for Johnny’s reluctance to write stems from teaching approaches that neglect the affective aspects of writing – the feelings, emotions and attitudes involved in learning to write. Children and young people have reported feeling physically sick and in a state of mental agony when they are in the writing classroom⁹. When so many children associate writing with feelings of incompetence, dread, fear and anxiety, even seemingly capable writers fail to find the motivation to engage, persist and take the risks necessary to produce their very best writing.

A lack of confidence

A lack of confidence in writing is deeply tied to low self-efficacy, which is defined as self-belief, self-esteem, self-worth, and self-affirmation. When children have low self-confidence as writers, they generally dislike writing¹⁰. They may believe they cannot improve and therefore do not seek writing advice, instead writing only the minimum required. This can lead to low aspirations, a sense of learned helplessness, and little commitment to class writing projects. Children with low self-efficacy may express negative views of themselves and can even become depressed.

Unfortunately, too many children, too often, are failing to meet the basic met standard for writing. This lack of competency and success invariably hits their confidence hard. Therefore, one of the best ways to help Johnny want to write is to ensure he regularly feels a sense of success. How is this done? By ensuring he is in regular receipt of the best evidence-informed writing practices⁴.

A lack of independence

A lack of independence in writing is closely linked to low self-regulation, which involves knowing what to do and how to do it for oneself¹¹. Too often, children are assigned a lot of writing without ever being shown what to do and how to do it by a passionate writer-teacher. Children with low levels of self-regulation often lack the strategies and techniques needed to sustain a piece of writing successfully. They may resort to avoidance tactics, such as procrastination or hiding their work, and spend minimal time engaged in the writing process. Their focus tends to be primarily on handwriting, spelling, and punctuation, while they struggle with generating ideas, planning, attending to class writing goals, revising their compositions, and proof-reading final drafts.

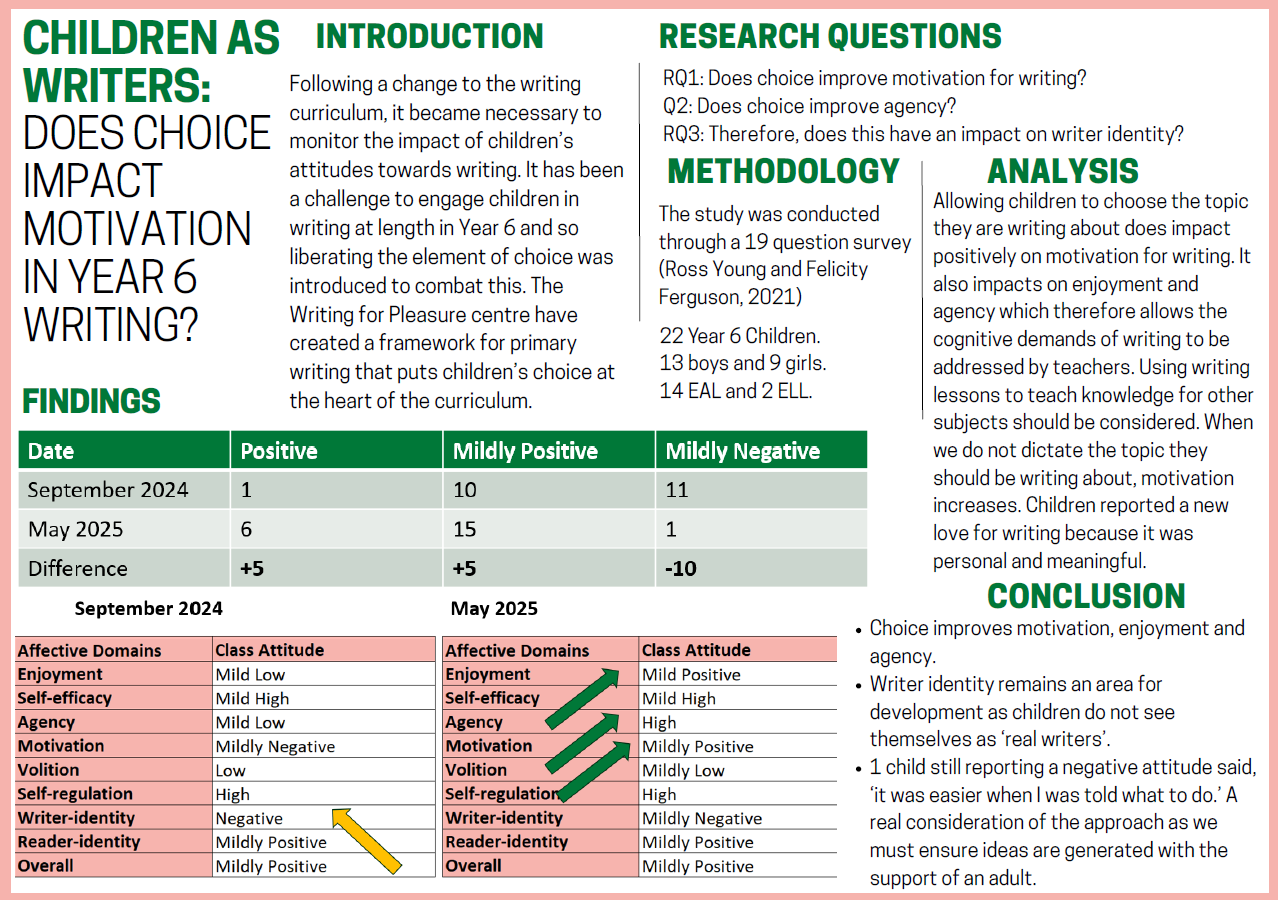

A lack of autonomy

Agency in writing means having choice, support, autonomy, and ownership over your ideas, your processes, and even aspects of what you are taught. Sadly, children are rarely shown explicitly how to generate their own writing ideas nor are they invited to make contributions to the class’ criteria for success¹². Instead, this role is often taken over by scheme writers, without good reason and with largely negative consequences.

When children have no say over their writing topics, they are assigned tasks on subjects they neither know nor care about. Disengagement and disenfranchisement soon follow. Donald Graves famously warned that assigning topics creates a ‘welfare system,’ where children are only ever ‘renting a writing idea’ rather than ‘owning it for themselves,’ resulting in a lack of care or commitment to its quality. In these scenarios, children quickly see through the illusion: they are not crafting their own text at all, but merely there to transcribe the scheme writer’s ideas. The scheme writer enjoys the creative work; the child is left with the clerical labour. It’s hardly surprising, then, when they ask: ‘Why should I care if this writing does well?’

A lack of purpose

Authentic writing is an outcome where a child judges there to be a strong connection between a class writing project and their own life, involving real-world relevance and value outside of school. Unfortunately, writing in school is often arbitrarily tied to tasks or texts chosen by a purchased scheme. Many involve inauthentic writing tasks that serve no purpose beyond teacher evaluation. Such tasks require minimal thought, minimal feeling, are often boring, and lack personal meaning, causing children to feel disengaged¹³. They rightly ask: What’s the point? Why am I doing this?

A lack of audiences

One of the most significant reasons children struggle to care about writing is the absence of a genuine audience. Too often, their manuscripts gather dust in their exercise books and exist only so they can be marked by their teacher. In such cases, children quickly learn that their compositions are little more than ‘fake artefacts,’ produced solely for the purposes of academic evaluation¹⁴.

What’s missing is the opportunity for children to gain real-world recognition and form meaningful social connections with a variety of readers through their writing. At its heart, writing is a social act, a way of making and sharing meaning with others. When young writers know their words will be published, shared, performed, or will be useful to others, they see their writing as consequential. This motivates them to care about clarity, craft, and quality not only because the teacher demands it, but because they believe their audience deserves it too. Without these authentic outlets, children are denied one of writing’s greatest rewards: the chance to entertain, connect, teach, influence, and matter.

A lack of healthy motivation

A core reason for writing underperformance is not simply a lack of skill, but a lack of healthy motivation¹⁵. Too often, children are writing not out of personal curiosity or pride, but out of fear of punishment or simply to keep their teacher happy. This dynamic undermines both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Instead of writing because they have something meaningful to say (intrinsic) or because their work will gain authentic recognition (healthy extrinsic), children write to avoid sanctions, tick boxes, or, at best, receive some fleeting praise.

When your teachers’ academic evaluation becomes your dominant concern, anxiety rises and so the risk-taking that’s required for the very best writing plummets¹⁵. Every writing event becomes a high-stakes act of compliance, where the focus is on producing ‘safe’ but accurate work rather than having the time to experiment with ideas, voice, and structure. While extrinsic motivators absolutely have their place, relying too heavily on pressure, rewards, or teacher approval leads children to associate writing with stress and obligation rather than self-expression and a personal sense of achievement. Over time, this performance-driven stance erodes children’s ability to see themselves as writers at all. Instead, they are at school to perform something that looks like writing.

A lack of personal passion projects

Volition is defined as the internal need, desire, urge, or compulsion to write. Writer-teacher Donald Graves famously told us that: ‘children want to write. They want to write the first day they attend school’. However, our teaching practices can significantly weaken this innate drive. Overuse of scheme-assigned topics, setting up inauthentic writing activities, and an almost exclusive focus on transcriptional errors in a high-stakes, performance-oriented classroom culture can diminish children’s volition to write¹⁶. While children are capable of generating their own ideas from an early age, this opportunity is often removed, with scheme-writers assuming responsibility for topic choice.

Personal writing projects, where children have the time, support and freedom to choose their own topic, genre, purpose, and audience, are crucial for developing their intrinsic motivation¹⁷. Unfortunately, personal writing is often relegated to short, low-status periods like ‘golden time’ or ‘Free Writing Friday,’ which sends a dangerous message about its value. The absence of genuine, self-chosen writing time limits children’s opportunities to explore, experiment, and even fail in a safe environment, preventing them from seeing writing as a genuine recreational activity they can do outside of school. We must remember that, for some children, school may be the only safe space to write for themselves, making the provision of such opportunities incredibly important.

A lack of satisfaction

When children’s writing is judged primarily on transcriptional accuracy or adherence to grammatical conventions, rather than on the quality of its content, style, originality, or its impact on readers, the result is often impeccable nonsense. An emphasis on technical correctness while neglecting meaningful communication leads children to produce texts that are transcriptionally sound but compositionally weak, offering them little satisfaction. When their efforts culminate in work that serves no real purpose and reaches no genuine audience beyond the moths in their exercise book, they come to feel that their writing is neither seen nor valued. The result is a loss of pride and satisfaction in their writing. Children deserve to feel:

- A personal sense of progress and pride

- Recognised by their readership and have the opportunity to make social connections with their audiences

- A sense of academic achievement

A feeling of alienation

For many children, the writing classroom is not a place of belonging but of exclusion. Their own funds of knowledge, funds of identity, and funds of language are often dismissed as unimportant, lacking in so-called ‘cultural capital,’ or even actively rejected as undesirable¹⁸. When the knowledge, experiences, interests, culture and linguistic repertoires children bring with them are sidelined, they quickly receive the message that their writing voice does not count.

This sense of alienation undermines both motivation and confidence. Writing becomes an act of conforming to someone else’s expectations rather than an authentic form of self-expression. Children learn to suppress their lived experiences, their home languages, and their own knowledge(s), producing writing that feels disconnected from who they are. In the long term, this not only diminishes their engagement with writing but also robs the classroom of the richness and diversity that genuine inclusion would bring.

How do we help Johnny?

The Writing for Pleasure pedagogy offers a comprehensive approach to address the issues of both underachievement and disengagement in writing. It is grounded in global research and the practices of exceptional teachers, aiming to develop children and teachers as extraordinary and life-long writers⁴. The approach is neither teacher-centred nor child-centred, but rather one centred around creating successful writers, combining rigorous instruction with principles that develop enjoyment and satisfaction.

References

- Children and young people’s writing in 2025 [LINK]

- Writing for Enjoyment and its Link to Wider Writing – Findings from our Annual Literacy Survey 2016 Report [LINK]

- Write to Read, Read to Write: Reimagining the Writing Classroom [LINK]

- The enduring principles of effective writing teaching [LINK]

- Teach mini-lessons [LINK]

- The Writing For Pleasure Centre’s Grammar Mini-Lessons [LINK]

- Reading In The Writing Classroom: A Guide To Finding, Writing And Using Mentor Texts With Your Class [LINK]

- Be a writer-teacher [LINK] and An action plan for world-class writing teaching [LINK]

- The affective domains of Writing for Pleasure [LINK]

- Self-efficacy [LINK]

- Self-regulation [LINK]

- ‘It’s healthy. It’s good for you’: Children’s perspectives on utilising their autonomy in the writing classroom [LINK]

- Pursue purposeful and authentic class writing projects [LINK]

- ‘Playing the Game called Writing’: Children’s Views and Voices [LINK]

- Motivating writing teaching [LINK]

- Volition [LINK]

- A guide to personal writing projects & writing clubs for 3-11 year olds [LINK]

- Writing Realities [LINK]