What is encoding?

Few aspects of primary education are as widely debated or misunderstood as the teaching of phonics and its relationship with early writing. Before we proceed further, it is essential to define what is meant by encoding and its associated terminology.

At the heart of the English writing system are relationships between the sounds of spoken language and the letters used to represent them. Encoding is the process of using these relationships to translate spoken words into written form. Specifically, encoding involves breaking spoken words into their smallest units of sound, called phonemes, and representing them with individual letters or small groups of letters, called graphemes. These relationships are known as grapheme-phoneme correspondences.

Encoding is a fundamental skill in early writing. It involves segmenting phonemes within words (e.g., ‘dog’ → /d/ /o/ /g/) and then selecting and arranging graphemes to form the conventional spelling. The ability to manipulate phonemes in this way, known as phonemic awareness, is a crucial part of learning to write (Cabell et al. 2023).

The word ‘encoding’ is sometimes used interchangeably with spelling. However, encoding is best understood as the skill of constructing written words from phonemes using a knowledge of grapheme-phoneme correspondences, as opposed to memorising how whole words are spelt.

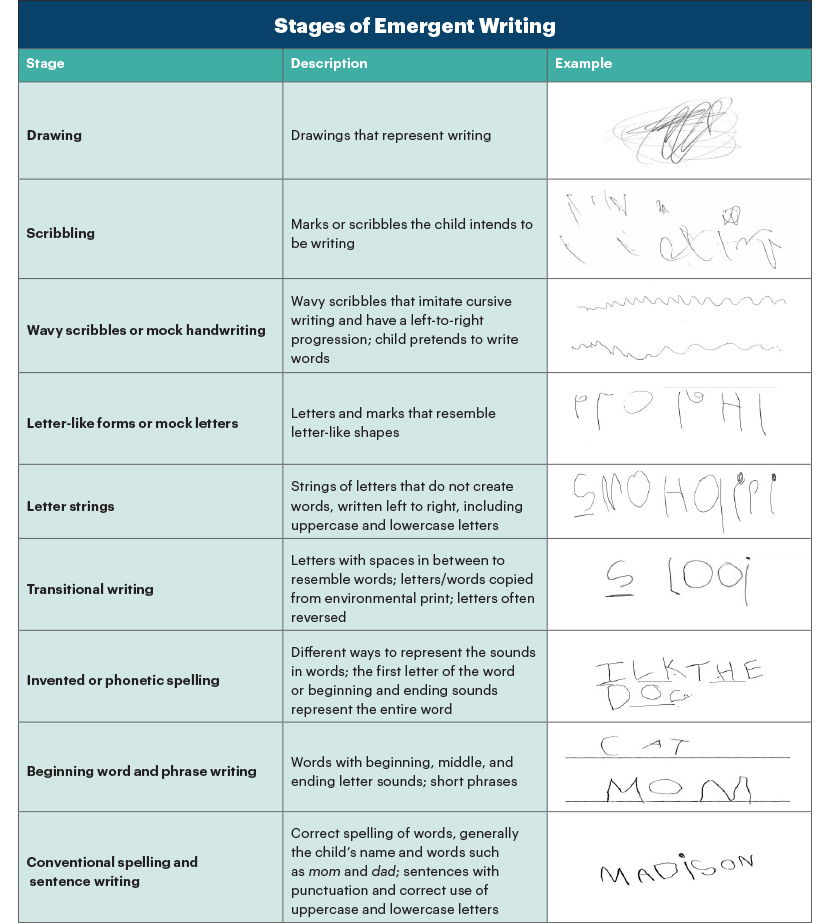

Instruction in encoding involves teachers modelling how they are listening to the sounds in the word they wish to write while transcribing those sounds on paper. We call this writing an ‘informed spelling’. It is ‘informed’ because the youngest of writers may still be developing their knowledge of ‘the code’ and can only use what they currently know. Therefore, they may skip or substitute unknown graphemes with a squiggle, line, or letter-like shape (see LINK for more).

When modelling encoding strategies, teachers should use the same resources they use for their phonics instruction: for example, showing children how they are referring to their sound mat to identify the letters they wish to transcribe on paper.

Why should we teach encoding?

The argument for teaching encoding is straightforward: in order to write in English, pupils must develop an understanding of grapheme-phoneme correspondences and how to apply them when spelling words. Without this foundational knowledge, pupils would be left to rely on inefficient strategies such as rote memorisation of whole words.

Learning to write fluently requires more than just expertise in encoding, but mastering this skill is a massive and necessary step toward proficient writing. The question is not whether to teach this code but how best to do so. While some pupils may quickly master the code independently, those who struggle with writing benefit most from regular and explicit encoding instruction (Young & Ferguson 2023). With explicit instruction in encoding and lots of meaningful writing experiences, children begin to write ‘informed spellings’ automatically without conscious effort (Cabell et al. 2023; Feldgus & Cardonick 2017).

What are the limits of encoding instruction?

Encoding is an essential component of early writing, but it is not the sole factor in developing proficient writers. Encoding instruction focuses on helping pupils develop an ability to move beyond using emergent writing (see LINK for more) to beginning to spell words conventionally in such a way that other people can read and understand what it is they want to share. However, English spelling is not entirely phonetic. For example, some words contain silent letters (e.g. knight and autumn), irregular spellings (e.g. one and said), or historical letter patterns that do not conform to standard grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules (e.g. ough). Therefore, any encoding instruction should also address aspects of morphology and etymology. Pupils will need exposure to high-frequency irregular words (a common word wall/word mat) and affixes (prefixes and suffixes we typically attach to root words). For example un-help-ful.

How do pupils become more expert at spelling?

In the early stages of writing, some words are easy to encode. For instance, if a pupil wants to spell pig, stop, in, on or fun their first attempt at encoding using their phonics knowledge will be likely to result in the conventional spelling.

However, some words present greater challenges. Consider the word because. If a pupil has not yet learned that unstressed vowels can be difficult to hear and that -ause does not follow regular phonetic patterns, they may initially spell it as becos or becuz. Similarly, friend may be spelled as frend because the silent i does not correspond to its pronunciation. The word said is often written as sed, as pupils expect ai to produce a long a sound rather than the short e it represents in this word. Likewise, they may be spelled as thay due to the irregular ey spelling for the long a sound. Finally, enough is frequently written as enuf, as young spellers simplify the unpredictable ough pattern to match the /f/ sound. However, there is still much to celebrate with these spellings! We can see the informed ways in which children are trying to ensure their readers can decode and read their writing. This is a beautiful thing!

To develop their spelling expertise, pupils must engage in frequent meaningful writing experiences, focusing on segmenting spoken words into phonemes and linking them to their corresponding graphemes. In the EYFS-KS1, we believe this is best achieved through picturebook making projects (see LINK and LINK for more details). This practice should be supplementented by explicit spelling instruction (see LINK for more) and actively teaching children how to proof-read for their spellings at the editing stage of a class writing project (see LINK for more on this). Combine this with copious amounts of reading and pupils will gradually refine their understanding of English spelling conventions.

How should encoding be taught?

Effective encoding instruction during writing lessons will naturally supplement a school’s chosen phonics programme. However, there are general principles that teachers should follow:

- Regular modelling of encoding strategies by teachers during writing lessons. See our publication: Getting Children Up & Running As Writers [LINK] as well as Kid Writing: A Systematic Approach to Phonics, Journals, and Writing Workshop by Eileen Feldgus & Isabell Cardonick for more details.

- Use structured routines. Consistent writing lessons and unit formats help pupils focus on their writing. Again, see our publications: Getting Children Up & Running As Writers, How To Teach Non-Fiction Writing In The EYFS and How To Teach Narrative Writing In The EYFS for more details [LINK].

- Ensure children are given a copious amount of meaningful writing experiences. Pupils need repeated opportunities to encode the words they want to write most to solidify their learning.

- Model segmenting words into phonemes. Teachers should avoid adding extra vowel sounds, such as pronouncing ‘p’ as puh instead of a crisp p.

- Maintain consistent terminology. Terminology used in writing lessons should align with your school’s phonics programme.

- Adapt to pupils’ accents. Encoding instruction should account for phonetic variations in pronunciation.

- Use responsive teaching. Assess pupils’ progress regularly and provide additional modelling during writing time for those who need additional support.

For school leaders, additional considerations include:

- Providing training for all staff involved in teaching children how to encode.

- Engaging parents in understanding how emergent writing transitions into informed spelling by way of encoding. Give parents advice on how they can support their children’s writing at home (see this link for a parent handout).

- Organising interventions for pupils needing extra support (see our publication Supporting Children With SEND To Be Great Writers for more information LINK).

Should morphology be embedded into encoding instruction?

Yes. When modelling their own encoding strategies, teachers should point out common spelling patterns related to morphemes, such as pluralisation (e.g. adding s) and common affixes (e.g., un- and -ing). This helps pupils understand spelling within the broader framework of English word structure.

Should children only ever write words they can fully encode?

There is no research which suggests that such an approach is desirable or necessary. Instead, children can be taught what to do when they can’t encode part of a word. For example, by drawing a line (Feldgus & Cardonick 2017).

Here we can see the child using lines when they are unable to encode certain words they want to write. We can then see the teacher’s responsive feedback through their underwriting.

Teachers can provide responsive feedback through underwriting. Underwriting involves transcribing a child’s writing using conventional spelling. This can be done either directly under or above the child’s writing, or sometimes at the bottom of the page. When done right, it can be a simple yet powerful tool to support young writers on their journey towards becoming a successful writer.

When underwriting, teachers may write:

- The whole sentence, phrase or choose a specific word.

- Words that are very close to the conventional ‘adult spelling’, giving you an opportunity to celebrate how closely the child approximated the word.

- High-frequency words that the child is likely or expected to know.

- Words that are so far away from the conventional spelling that they are difficult to interpret.

Underwriting should always be about emphasising and celebrating what the child did know about adult writing. When done correctly, underwriting offers numerous benefits:

- Providing a conventional model: Gives children who like it a reference for the conventional spelling which they may refer to later.

- Responding to a specific request: Supporting children who specifically ask for help in understanding and remembering what their writing says.

- Verbal feedback: It offers opportunities for individualised responsive instruction during verbal feedback.

- Celebrating growth: It celebrates children’s approximations, what they did know about the ‘adult spelling’ of the word and therefore gives children confidence and a sense of achievement.

Does underwriting make children scared to write and reduce ownership? A justified concern with underwriting is that, when it is done badly, it makes children scared to write for themselves. It can also be seen as an act of graffiti on a child’s writing – a daily reminder that they can’t actually write and that someone has to come and do it for them. It’s no fun giving something like writing a try if you are only ever going to be criticised for your efforts. However, when done thoughtfully, underwriting is a teaching tool, not a correction mechanism. Best practice for underwriting includes:

- Having the child’s consent and with them present.

- Celebrating and building on what the child did know about the ‘adult spelling’.

- The teacher using a pencil and small writing, usually at the bottom of the page.

- Never underwriting before the child has made their own attempts at the word, phrase or sentence first.

- Not doing it with every child, all the time, and on every piece of writing they produce.

Underwriting is a tool for progress and celebration. Some children enjoy seeing how their writing compares to ‘adult writing’. However, others can get really upset and feel undermined. For some, it can be the equivalent of making a lovely drawing for their teacher – only for them to get a red marker pen out and draw all over it to ‘make it correct’. If this happens day after day, some children can soon lose their motivation and confidence to write independently. With that said, if the purpose of underwriting is clearly explained, children often appreciate the thoughtful and interesting feedback it provides.

Concluding thoughts

Alongside explicit teaching, children should regularly engage in meaningful writing experiences. In the EYFS-KS1, this is best achieved through book-making (see our EYFS publications here for more details) Children should feel free to write any words they want to use in the books they are making, even if their spellings are informed but not yet conventional. Children should be supported with sound mats, word banks, high-frequency word displays, guided practice and proof-reading sessions. Over time, as pupils develop confidence and proficiency, they should be encouraged to take greater risks in spelling unfamiliar words by writing ‘temporary spellings’.

A temporary spelling is a child’s best approximation. They then put a circle around that word – knowing that they will be given proof-reading time later in the writing unit to correct it.. During proof-reading sessions, children look up the conventional spelling, cross out the temporary spelling and write the correct spelling above it. For more on delivering these kinds of proof-reading sessions, see our publication: No More: ‘My Class Can’t Edit!’ [LINK].

By the end of their second year of formal writing instruction (Year 1 in English schools), most pupils should be able to apply their phonological and morphological knowledge independently to produce informed spellings and spell many ‘phonetically predictable’ words correctly. However, encoding instruction should continue throughout primary school to support children’s ongoing spelling development and mastery of the complexities of English orthography.

You can check your school’s spelling provision by using our provision checklist. You can download this checklist for free here.

To find out more about teaching spelling beyond Year 1, we can highly recommend the following publications:

- Adoniou, M., (2022) Spelling it out: How words work and how to teach them Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Bear, D. R., Invernizzi, M., Johnston, F., & Templeton, S. (2020) Words their way: Word study for phonics, vocabulary, and spelling USA: Pearson

- Gentry, J. R., & Ouellette, G. (2019) Brain words: How the science of reading informs teaching USA: Stenhouse Publishers

- Stone, L. (2021) Spelling for Life: Uncovering the simplicity and science of spelling London: Routledge

- Westwood, P. (2014) Teaching spelling: Exploring commonsense strategies and best practices London: Routledge

References:

- Byington, T. A., & Kim, Y. (2017). Promoting preschoolers’ emergent writing. YC Young Children, 72(5), 74-82

- Cabell, S. Q., Neuman, S. B., & Terry, N. P. (2023). Handbook on the science of early literacy USA: Guilford Press

- Feldgus, E. G., & Cardonick, I. (2017) Kid writing: A systematic approach to phonics, journals, and writing workshop. Wight Group/McGraw Hill

- Young, R., Ferguson (2019) Supporting children’s writing at home Brighton: The Writing For Pleasure Centre [LINK]

- Young, R., Ferguson (2023a) Getting children up & running as writers Brighton: The Writing For Pleasure Centre [LINK]

- Young, R., Ferguson (2023b) No more: ‘My class can’t edit’: A whole-school approach to developing proof-readers Brighton: The Writing For Pleasure Centre [LINK]

- Young, R., Ferguson (2024a) How to teach non-fiction writing in the EYFS Brighton: The Writing For Pleasure Centre [LINK]

- Young, R., Ferguson (2024b) How to teach narrative writing in the EYFS Brighton: The Writing For Pleasure Centre [LINK]