On the 7th of October 2025, the National Literacy Trust published findings from its newest survey entitled: Children & Young People’s Writing In School in 2025. It gathered views from around 15,000 children and young people aged 8-18 from 90 schools across the UK. The report examines their views on writing and on the writing instruction they receive. By listening to the voices of young writers, the study looks to better understand the disconnect between curriculum requirements, governmental policy and writing as a personal and socially meaningful practice.

***

As teachers, we work hard to equip children and young people with the essential skills they need to thrive in the broadest sense. Writing is one of the most fundamental of these skills, crucial not just for academic success but for self-expression, social connection and future career prospects. Yet, the National Literacy Trust’s latest data paints a worrying picture of a deepening crisis in writing attainment and motivation across England.

In 2025, around 30% of 11-year-olds in England left primary school unable to write at the minimum expected standard. This attainment gap is concerning as is the motivational landscape. Only around 30-40% of students actually enjoy writing at school.

In addition:

- Gender: More girls (44%) than boys (34%) enjoy writing at school.

- Age: Enjoyment drops significantly with age. 50% of children aged 8-11 enjoy writing but this goes down to around 30% among 14-16-year-olds, suggesting a significant dip during mid-adolescence. Interestingly, enjoyment then increases slightly amongst 16-18 year olds to just under 40%. Of course, none of this is anything to celebrate.

- Socioeconomic status: Children and young people receiving Free School Meals (FSMs) report enjoying writing more (41%) than their non-FSM peers (37%).

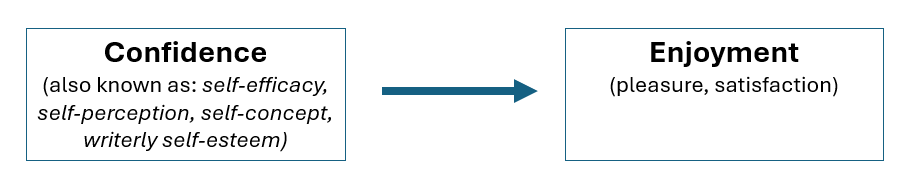

1. The relationship between confidence and enjoyment

The link between confidence and enjoyment is critical for classroom practice. Nearly 90% of students who enjoy writing at school consider themselves to be accomplished writers.

It’s very difficult to write with enjoyment if you feel you’re not very good at it. Confidence is one of the biggest predictors of children’s writing achievement¹. So, what practices have a track record for improving children’s writerly confidence²?

- Study mentor texts [LINK] With students, study and discuss texts that actually realistically match the type of writing they are being asked to write for themselves. This provides them with examples to emulate and learn from. This builds up their writerly confidence.

- Establish success criteria together [LINK] While reading mentor texts, collaborate with students to identify the techniques necessary for crafting their own high-quality texts. Make a commitment to teach these techniques, developing a sense of ownership and confidence among your students.

- Model craft moves [LINK] Demonstrate how to use a craft move before inviting students to do the very same in the context of their own writing. Modelling provides clarity and confidence, helping students grasp concepts more effectively.

- Set process goals [LINK] Encourage students to focus on a specific goal during writing time. By breaking down the writing process into small manageable chunks, students can see themselves making progress every day and this breeds confidence.

- Support children to choose their own writing topics [LINK] There are cognitive and motivational benefits to supporting children to choose their own writing ideas within the parameters of a class writing project. Being able to draw on a topic stored in their long-term memory (and one they are highly motivated to write about) fills them with writerly confidence.

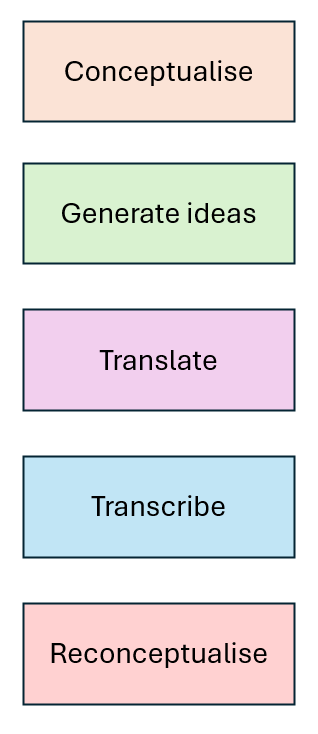

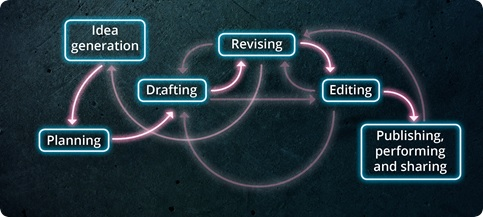

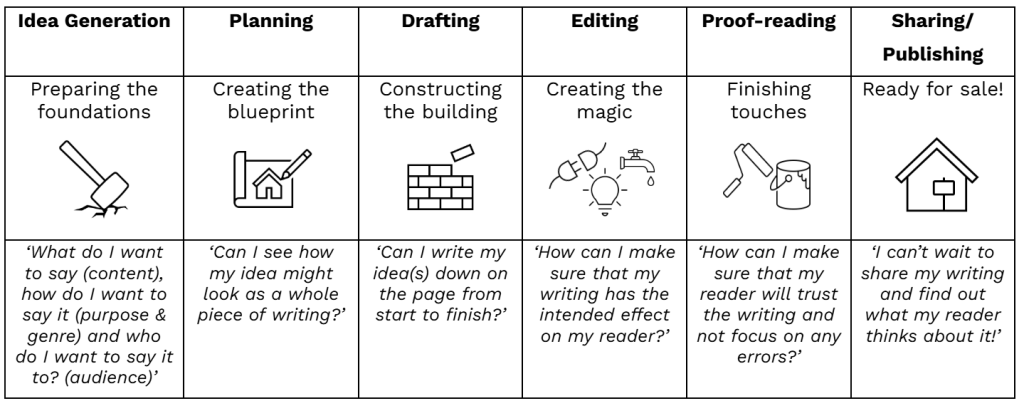

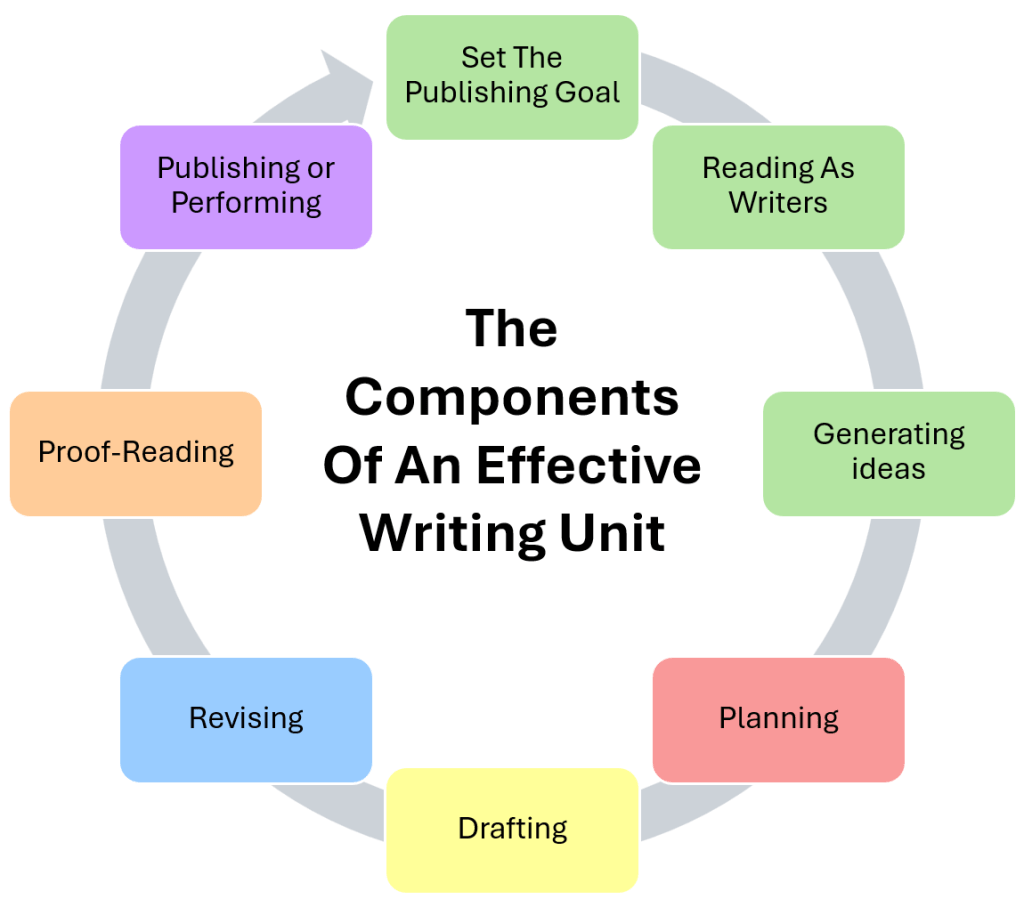

- Teach the writing processes [LINK] Design class writing projects that encompass all stages of the writing process, from generating ideas to publishing. Allocate time for instruction on each stage. This establishes a sense of daily progress, reassurance and success.

- Provide verbal feedback [LINK] Provide students with personalised feedback on their writing, both from their teacher and their peers. Effective verbal feedback reinforces successes and nudges students to apply constructive feedback quickly and confidently.

2. Redefining purpose: Intrinsic and external expectations

When the NLT asked students why they are moved to write, their answers revealed what they perceive the purpose of writing at school to be. Their reasons for writing were often shaped by external expectations and pressures. Indeed, 40% of children and young people admitted they wrote solely out of compliance or to avoid punishment. Some students did share other motivations. For example:

- To achieve good marks (37%).

- To secure better job opportunities (27%).

- To express their creativity (35%)

- To explore ideas (34%)

- To reflect on and deal with their emotions (24%)

- To better understand new learning (24%)

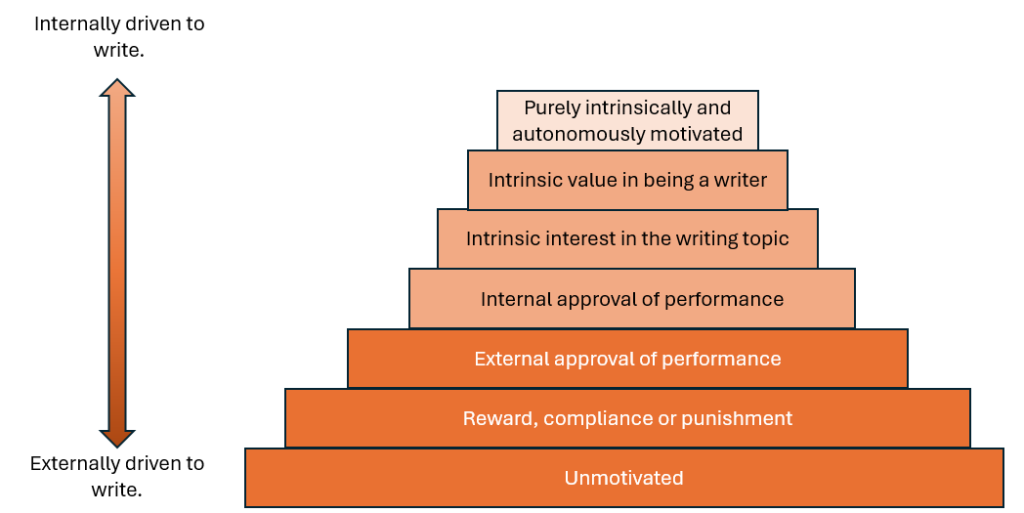

It can be useful to consider why children are motivated to write at school. Research consistently shows that students who write for external, teacher-controlled reasons tend to demonstrate poorer writing performance. In contrast, intrinsic motivation is linked with better outcomes³. However, it is important to recognise that extrinsically motivated young writers can also thrive, particularly when external rewards or recognition align with their personal goals and interests anyway⁴.

It’s very difficult to write at your best if you’re not motivated. Pupils who are motivated to write are more likely to: put in more effort, persist for longer, pay more attention, show more enthusiasm and work harder to solve their own writing problems⁵. It’s therefore important that we nurture the ‘will’ to develop the ‘skill’. A drop in motivation is a serious threat to student engagement.

- Embrace intrinsic value: Writing in school should be framed as a personally and socially profound activity, one that helps students make and share meaning, develop their ideas and understanding, cultivate their artistry and imagination, and articulate their thoughts, funds-of-knowledge, opinions, and feelings. By doing so, they can achieve exceptional academic outcomes.

- Not either/or: Students who view themselves as good writers are motivated by academic goals, intrinsic factors like self-expression and making social connections with others through writing.

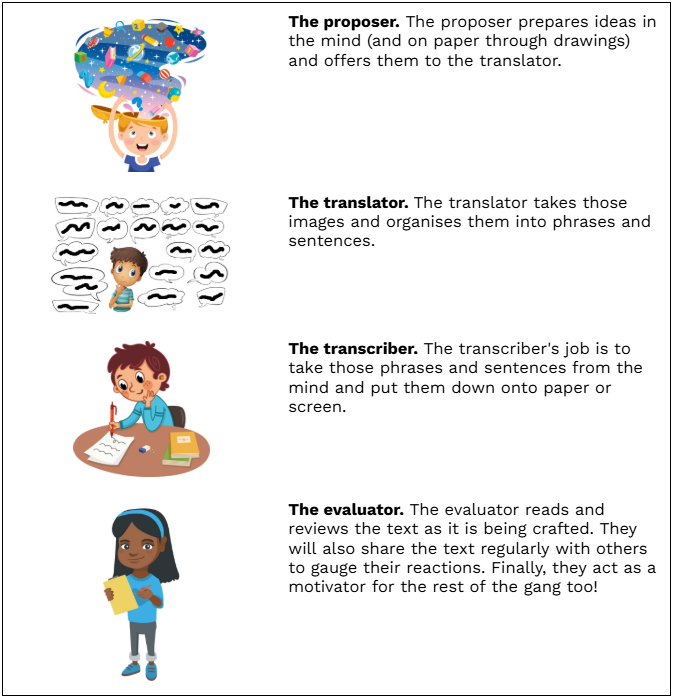

3. Teaching the writing processes: Confidence gaps and strategy use

A common misconception is to assume that students are either confident and competent writers or they’re not. In reality, their confidence can be subject to change depending on what aspect of the writing process they currently find themselves in. For example:

- Pupils are most confident in generating writing ideas (73%)

- Students are not confident to proof-read (50%)

- Students also lack confidence in sharing, performing and publishing their writing (43%)

- Pupils lack confidence in revising (53%)

It’s very difficult to produce your most meaningful and academically successful writing if you don’t have the strategies to do so. Children who know the writing processes, and have internalised strategies and techniques for negotiating them successfully, produce better writing⁷.

- Teach planning techniques [LINK] Students appreciate being taught how to use a variety of intuitive planning strategies.

- Plan revision sessions into your class writing projects [LINK] Students showed an overwhelming preference for experimenting and revising their writing but only after they’ve drafted.

- Explicitly model how proof-readers edit [LINK] Model an aspect of proof-reading in your own writing before inviting pupils to do the same during that day’s writing time.

- Establishing a publishing goal for class writing projects with your class [LINK] Children appreciate being invited to consider whom they want to share or perform their writing to, and how they wish to publish it, as part of a class writing project.

Utilising self-regulation strategies in the face of difficulty

When students get stuck, their most common response is to stop and think (43%), or to ask for help (24%). However, only a minority (16%) of students reported independently trying different things out when stuck, demonstrating a lack of self-regulation. The link between enjoyment, confidence, and self-regulation is profound⁷.

- More of those who enjoyed writing persevered and tried new strategies (20%) and fewer gave up (3%) compared with those who didn’t enjoy writing (13% gave up).

- Those who rated themselves as good writers were more inclined to pause and reflect or try out a new strategy.

It’s very difficult to enjoy or succeed at writing if you feel like you always need assistance. Developing children’s self-regulation skills is probably the most effective thing a teacher of writing can do in their classroom⁷. So, what does this mean?

Get your writing instruction right [LINK]. Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) is by far the most thoroughly researched and consistently effective approach to teaching writing. It explicitly teaches students evidence-based strategies for generating ideas, planning, drafting, revising, and proof-reading, while also developing their ability to monitor and manage their own writing process. SRSD blends cognitive strategy instruction with self-regulation techniques, helping children not just to know what good writing involves, but how to do it for themselves. Studies show that SRSD benefits struggling and proficient writers alike, improving both the quality and quantity of their writing. However, despite its strong evidence base and adaptability across ages, genres, and abilities, SRSD remains virtually absent from most UK classrooms. Few teachers encounter it in their initial training, and fewer still receive professional development in how to implement it. As a result, one of the most effective tools for improving writing outcomes (and for giving children the confidence to see themselves as independent writers) remains unused in the very places where it is needed most.

4. The social and emotional landscape: Anxiety and dependence

The social and emotional environment of the writing classroom profoundly shapes student engagement⁵. At present, writing evokes considerable apprehension and anxiety in pupils.

- Worrying about correctness at the wrong time: One in three students worries about their grammar, punctuation and spelling while they are drafting.

- Avoidance: Three in ten avoid experimentation for fear it might go wrong. A quarter of pupils felt discouraged from writing altogether due to their teacher potentially identifying mistakes.

- Widespread fear: While anxiety was highest among poor writers, fear was widespread even amongst those who rated themselves as good writers.

Anxiety is the enemy of good writing. Students are often afraid of making errors while drafting, worrying that these mistakes will be seen as unacceptable or as evidence of poor writing. This has serious consequences: children who experience writing anxiety typically produce less, do only the minimum required, and avoid taking creative risks⁵.

It’s difficult to enjoy or produce your best writing in a climate of fear. Research suggests that the culture of writing in some schools places excessive emphasis on accuracy at the wrong stage of the writing process⁸. It may be that colleagues would benefit from CPD in how to plan a writing unit [LINK] and how to deliver sympathetic and useful feedback to pupils [LINK].

5. A klaxon call for collaboratively-controlled writing projects

- A call for structure, guidance and instruction: Nearly half of the students surveyed expressed a preference for clear, structured guidance from their teachers on how to craft a great piece of writing.

- Desire for some authorial control: Simultaneously, autonomy was a massive motivator. Half of students said they would write more, and with greater frequency, if given trust and guidance to choose their own writing topics within the parameters of class writing projects.

This is not a rejection of structure. Students appreciate structure and reassuringly consistent routines¹⁸. Rather, it is a call for scaffolding that empowers them to exercise their own authorial agency.

- Implement collaboratively-controlled writing projects: Teachers should design class writing projects which are collaboratively-controlled by teachers and pupils together³.

- Support students to find value: Most students recognised the value of writing. However, over half of those who rated themselves as poor writers believed that ‘schooled writing’ lacked meaning or an authentic purpose. We must consistently provide purposeful and authentic class writing projects⁹.

6. Igniting the desire to write: The catalysts for engagement

Understanding what moves students to write most is both affective and effective practice⁵. Having authorial control was the strongest motivator:

- Choice over writing topic: Students cited being supported to choose what they wanted to write about as their greatest cognitive and motivational driver¹⁰.

- Choice over style and form: 30% wanted to decide on the form or style of their writing.

- Personal expression: 28% want permission to express their own thoughts, funds-of-knowledge and opinions through their writing.

- Utilising intertextuality: 27% want permission to riff off their favourite authors to produce their own writing¹¹.

Perhaps understandably, only 16% saw value in being given a writing prompt. This is probably because it represents what’s called ‘an empty choice’¹².

The desire for some authorial control is linked to engagement: those who enjoy writing are much more likely to be motivated by creative freedom and personal expression. When given the support to choose their own topics and forms, students express overwhelming preferences for class projects that are exciting, personally meaningful, and allows for exploration:

- Topics: Preferences are varied, including writing about horror, history¹³, mysteries, sport¹⁴, adventure and murder cases. Students also want to share, through writing, their own funds-of-knowledge and cultural passions¹⁵. They also desire opportunities to write about real-world issues that matter to them personally¹⁶.

- Genres: Fiction and poetry dominate, with genres such as fantasy, detective fiction, lyrics, and script writing repeatedly mentioned. There is also notable enthusiasm for writing intended for performance and for forms inspired by visual media, such as comics and manga [LINK]. Students would also value learning how to write personal narratives, such as memoirs [LINK].

Conclusion

The findings from this report compel us to rethink not just how we teach writing, but why¹⁷. We see a clear tension: students value writing yet many feel increasingly anxious and disengaged when writing at school. Writing is most meaningful when students can relate it to their own lives and interact with others as authors. After all, writing is about making and sharing meaning⁵.

With this in mind, the most powerful catalysts for pupil engagement lie in helping students find intrinsic value in their writing: personal relevance, emotional resonance, authorial control, and social interaction with readers. By embracing teaching practices that combine explicit instruction, modelling, and guidance with opportunities for choice and supportive writing processes, we can move beyond writing as formalism and unlock its full potential as both a critical learning tool and a powerful form of self-expression.

References

- Self-efficacy [LINK]

- The enduring principles of effective writing teaching [LINK]

- ‘It’s healthy. It’s good for you’: Children’s perspectives on utilising their autonomy in the writing classroom [LINK]

- Reflexive writing dialogues: Elementary students’ perceptions and performances as writers during classroom experiences [LINK]

- Motivating writing teaching [LINK]

- See ‘teach the writing processes’ [LINK] and ‘self-regulation’ [LINK] for more.

- Self-regulation [LINK]

- Debunking edu-myths: Writing errors form bad habits [LINK]

- Pursue authentic and purposeful writing projects [LINK] and ‘Establishing publishing goals for class writing projects [LINK]

- The cognitive and motivational case for inviting children to generate their own writing ideas [LINK]

- Intertextuality. The glue that binds reading for pleasure and writing for pleasure together? [LINK]

- When choice motivates and when it does not [LINK]

- Historical accounts/essays [LINK], biographies [LINK] and people’s history [LINK]

- Match reports [LINK]

- Writing realities framework [LINK]

- Discussion essays [LINK], persuasive letters [LINK], advocacy journalism [LINK], community activism [LINK] and social/political poetry [LINK].

- ‘Teachers’ orientations towards teaching writing and young writers’ [LINK] and ‘Six discourses, four philosophies, one framework: A critical reading of the DfE’s writing guidance’ [LINK]

- Be reassuringly consistent [LINK]