Because of formatting, we can recommend downloading the PDF version of this article:

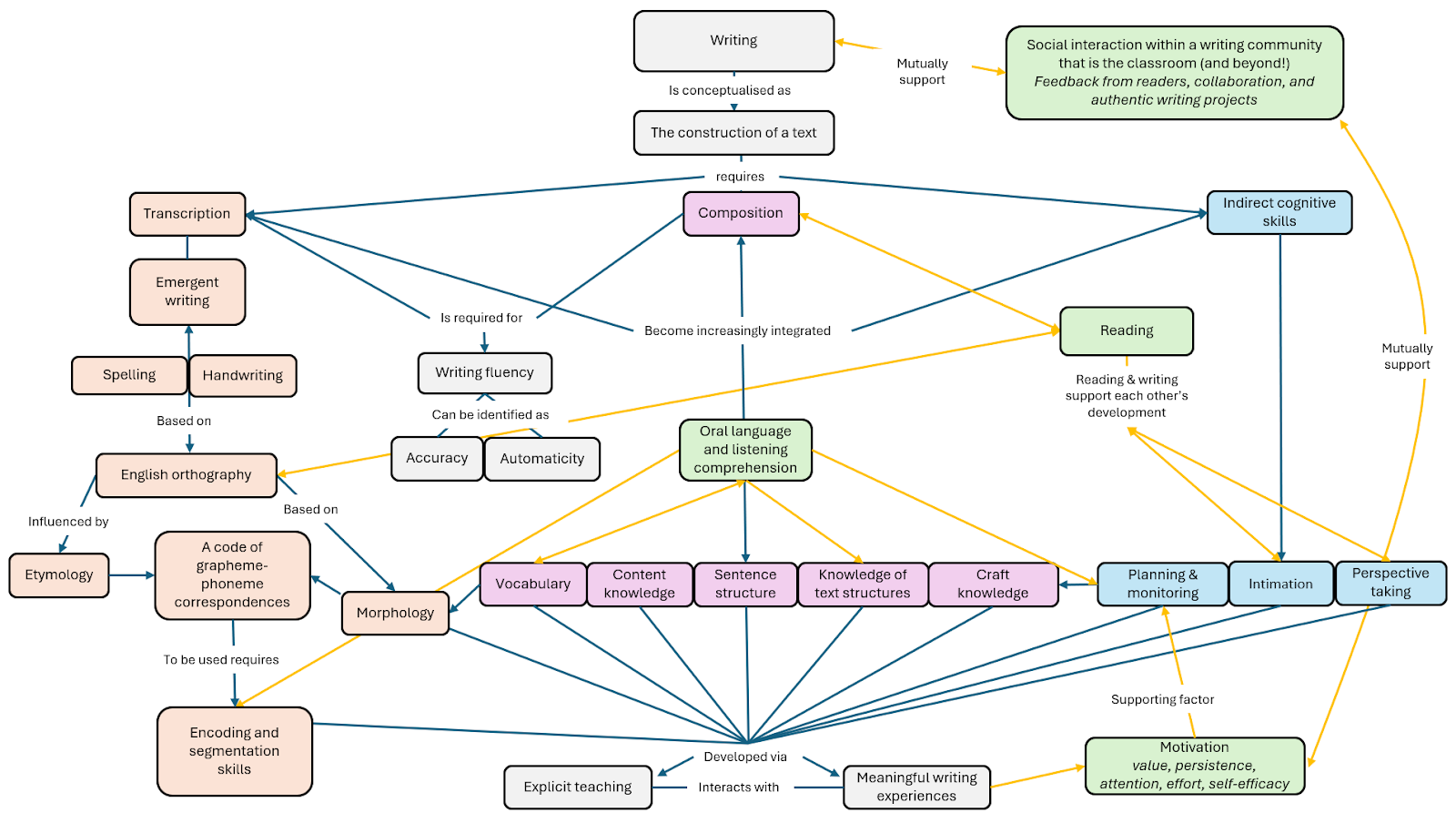

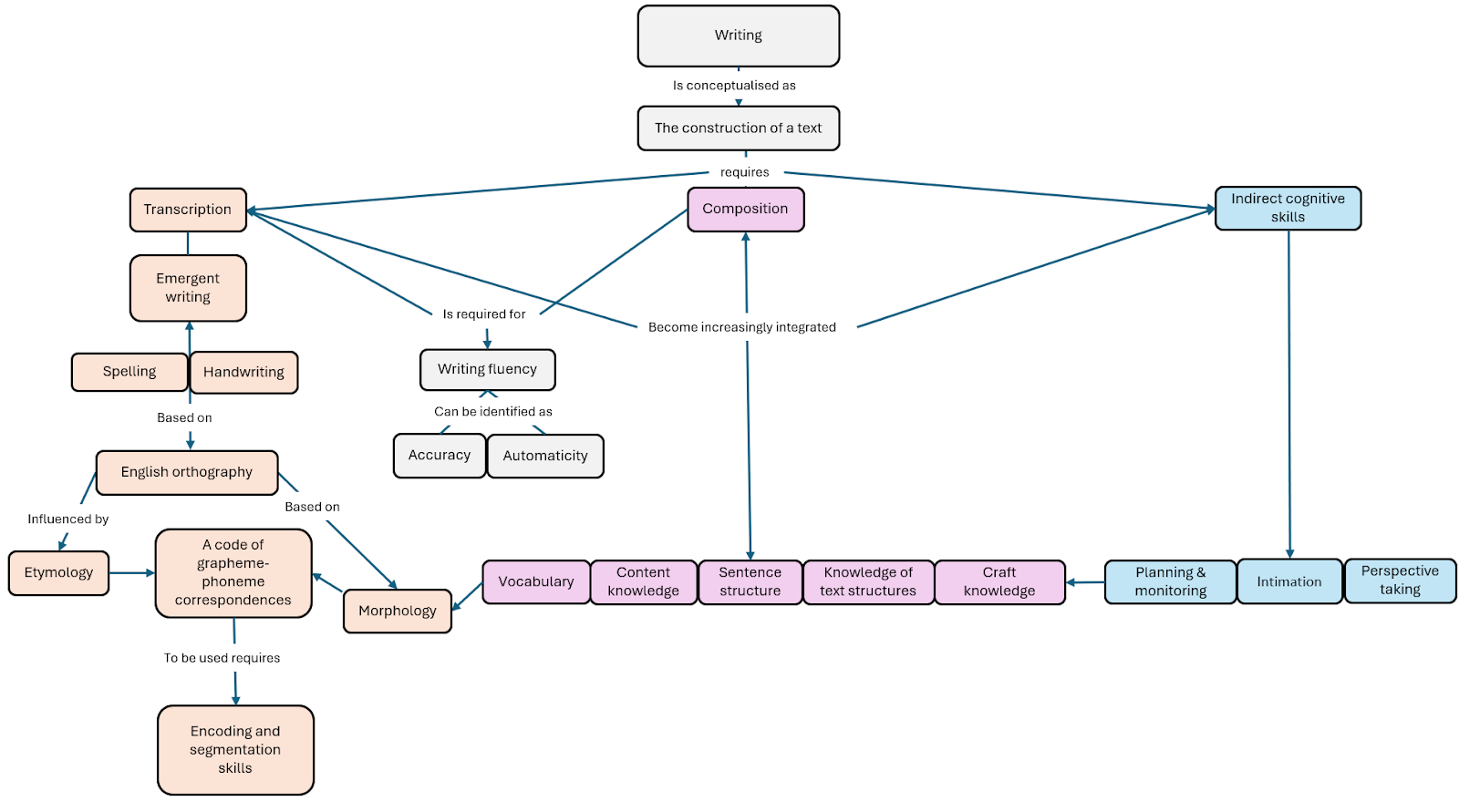

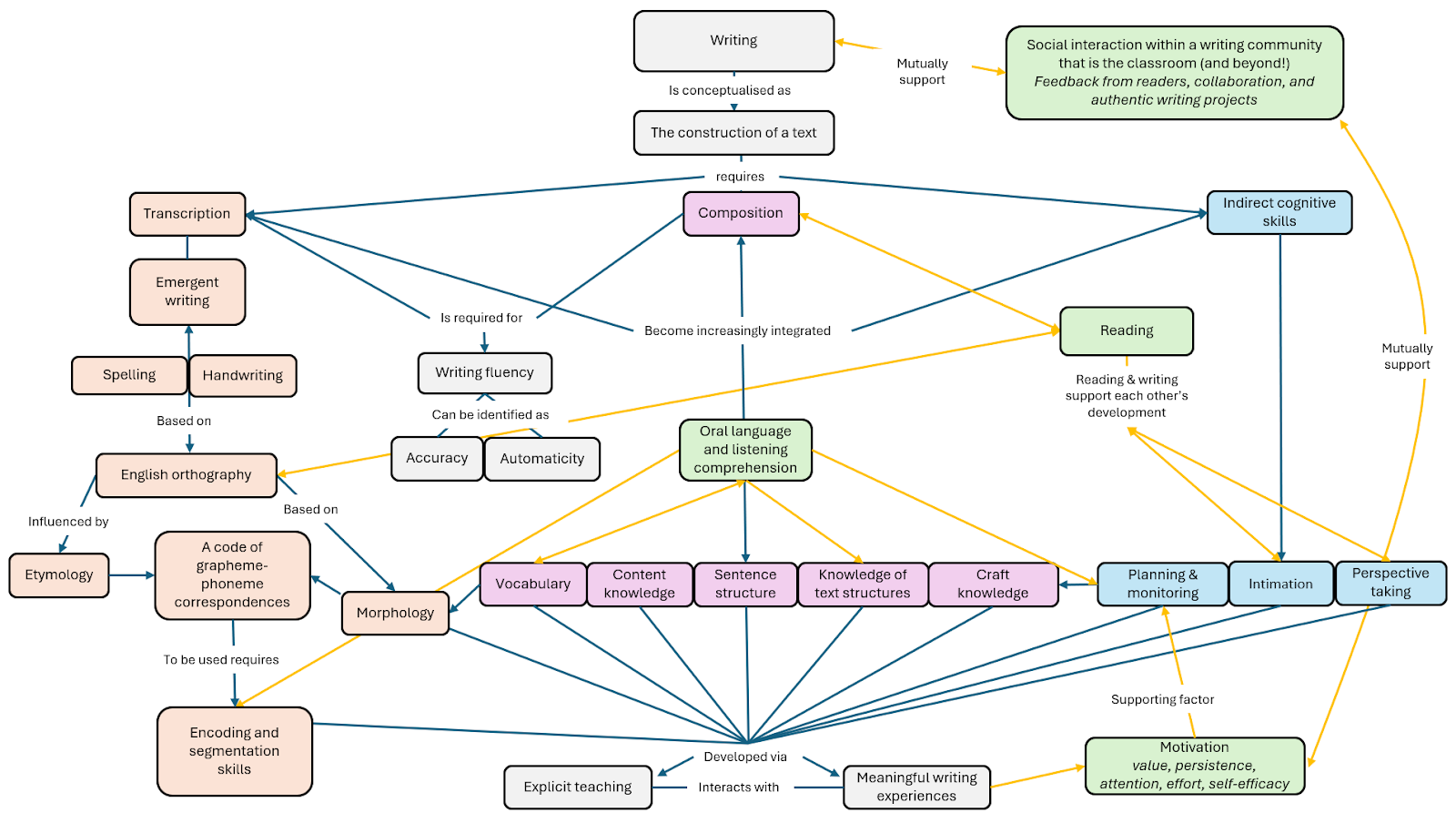

In our professional development work, we have found that a clear and structured understanding of writing development is essential for effective teaching. To support this, we created our writing map – an equivalent to Christopher Such’s reading map (which we highly recommend viewing here). Our writing map doesn’t just serve as a theoretical model for writing – it also serves as a practical guide for teachers and school leaders looking to strengthen their writing instruction.

Through our work with schools, we have observed that those with a strong grasp of these underlying principles are more confident and strategic in shaping their writing curriculum. However, many schools seek greater clarity in how to apply this knowledge effectively. This is where the writing map plays a crucial role – it bridges theoretical understanding with effective classroom practices, helping teachers and leaders make evidence-informed decisions about their school’s writing approach.

In this article, we will explore how the writing map aligns with the most effective writing practices, guiding you through its key components step by step. You can find an explanation of the writing map itself here.

Conceptualising Writing

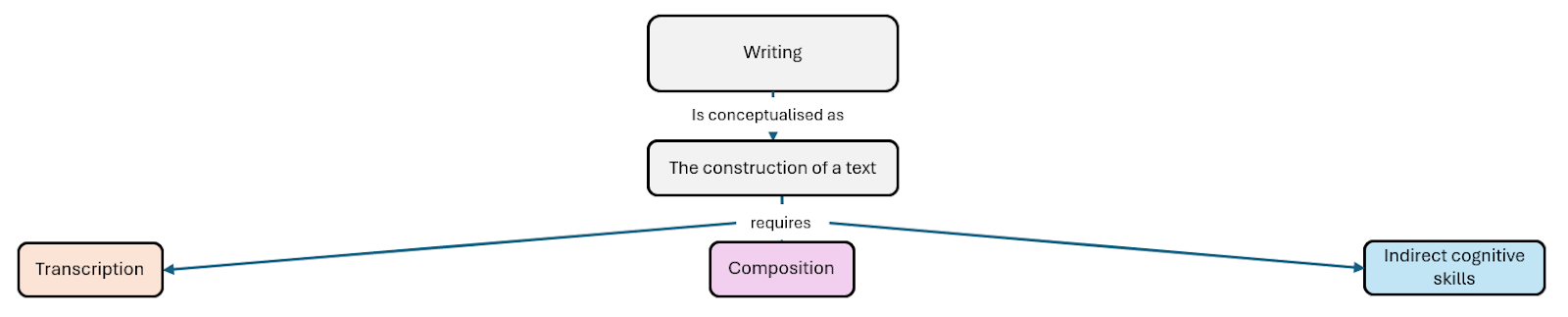

Writing can be defined simply as: the construction of a text to share meaning.

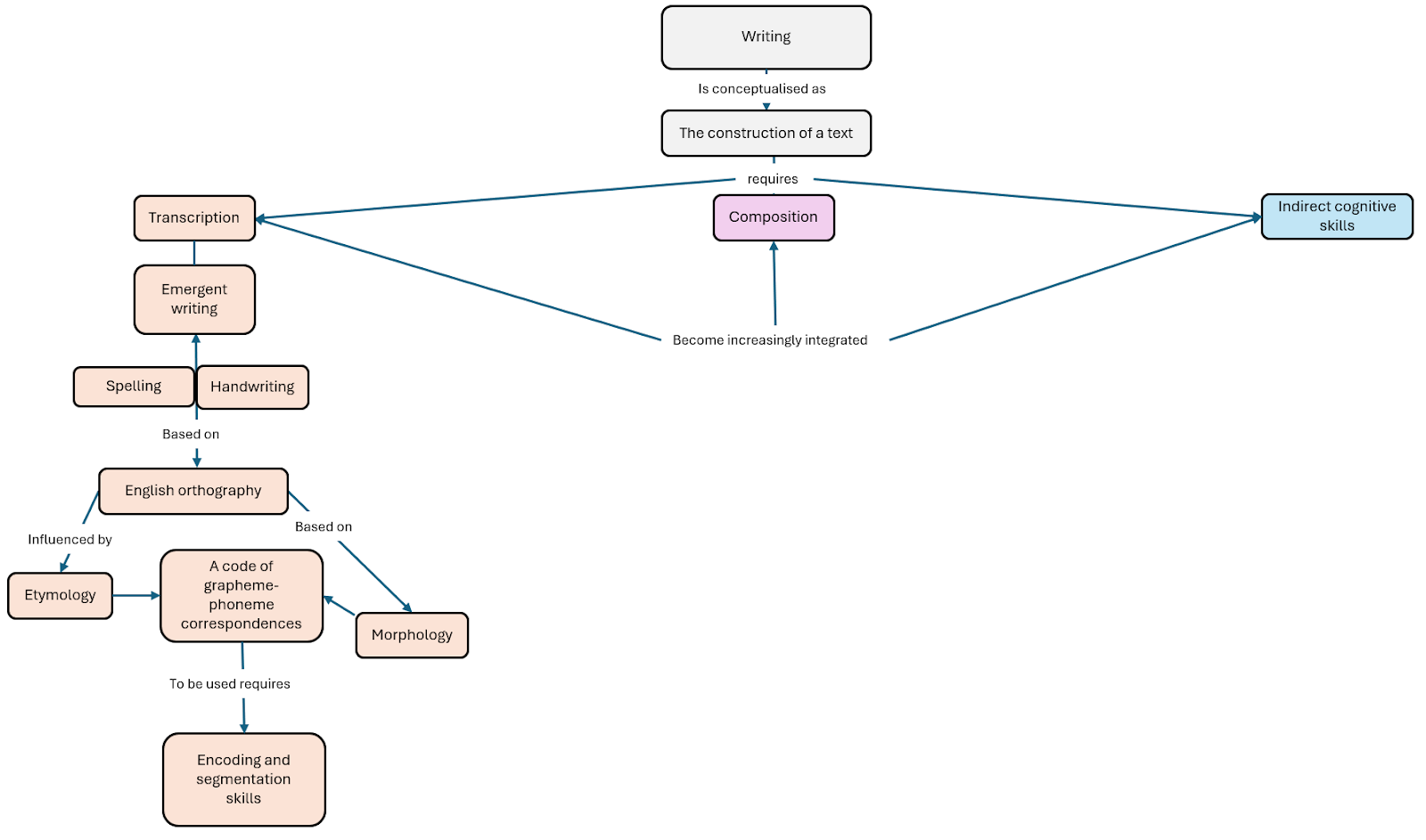

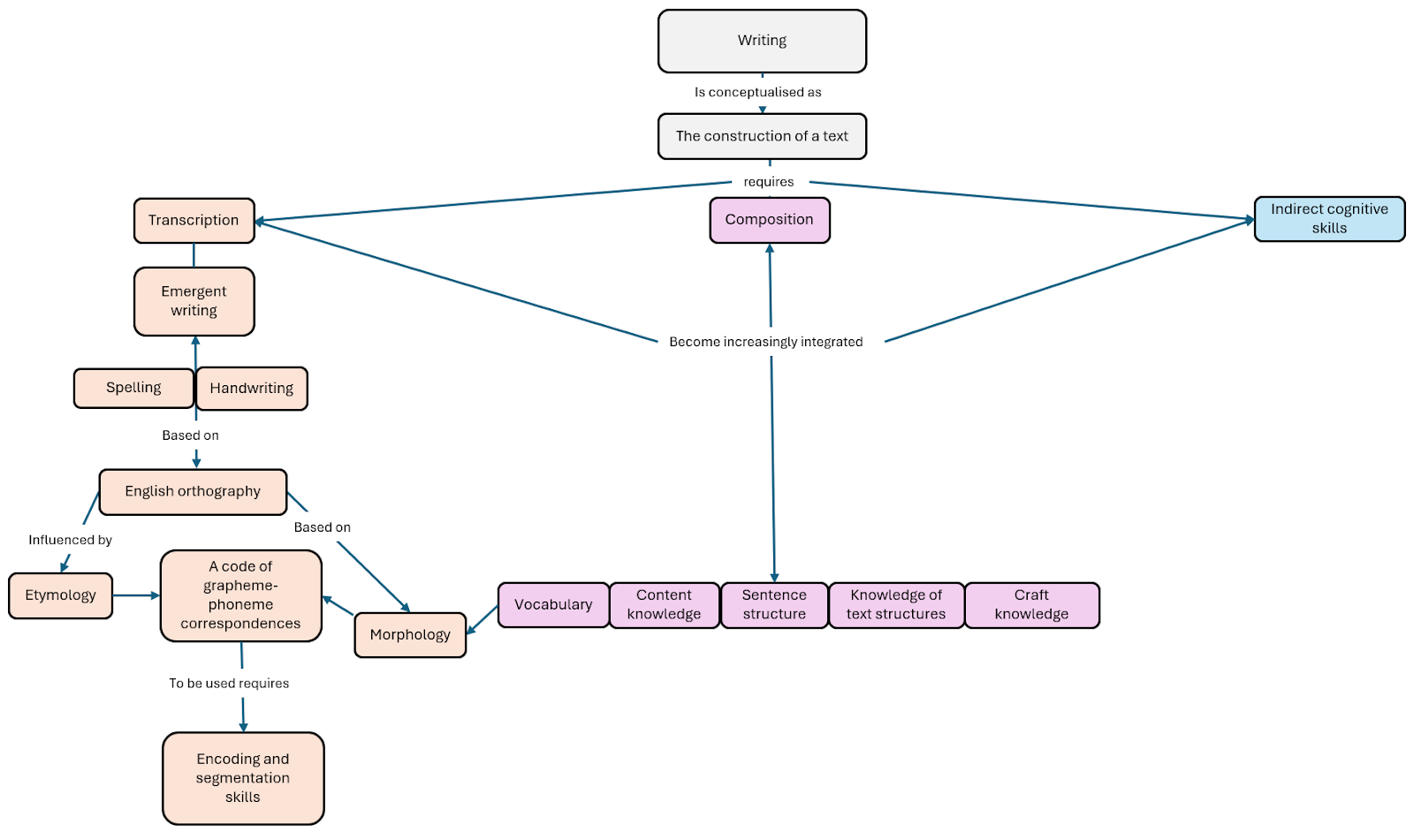

The construction of a text requires a young writer to draw on their knowledge of transcription, composition and other indirect cognitive skills.

Transcription, composition, and indirect cognitive skills become increasingly integrated as a young writer develops. Their proficiency follows a gradual developmental trajectory, where these components become more and more interconnected and automated over time.

Transcription

To help develop children’s transcription, teachers can:

From Nursery onwards, encourage children to engage in emergent writing practices. This includes going through a developmental process of making scribbles, marks, producing letter-like shapes before eventually using ‘informed spellings’. Emergent writing is a temporary scaffold that children use while they are in the process of developing their letter formation, encoding and spelling knowledge. To find out more, download our article:

- How can you teach children to write before they know their letters? [LINK]

Once phonics teaching has been introduced, you can begin to teach children encoding strategies which will wean them off their emergent writing practices towards writing ‘informed spellings’. To find out more, download our article:

- Encoding and ‘informed spelling’ [LINK]

We can also recommend our publication Getting Children Up & Running As Writers [LINK] as well as Kid Writing: A Systematic Approach to Phonics, Journals, and Writing Workshop by Eileen Feldgus & Isabell Cardonick.

Next, schools can check their handwriting and spelling provision against our checklist. You can download this checklist separately here.

Composition

To help develop children’s composition:

Content knowledge. Teachers can explicitly teach children idea generation techniques so that they draw on ideas and knowledge held in their long-term memory. You can read more about the motivational and cognitive benefits of supporting children to generate their own writing ideas here.

Knowledge of text structures. Teachers can devote instructional time to the reading and discussion of mentor texts. These are texts which realistically match the type of writing children are being invited to produce for themselves. Through reading and discussion, the teacher and children can collaboratively generate a list of ‘product goals’ (also known as success criteria) that they believe are essential for making their writing meaningful and successful. To find out more, see the following:

- How to get success criteria right in the writing classroom [LINK]

- Reading In The Writing Classroom: A Guide To Finding, Writing And Using Mentor Texts With Your Class [LINK]

In addition, you can provide children with planning grids or graphic organisers which match the typical structure for the genre of writing they are being invited to plan for themselves. For more on this, see our publication: No More: I Don’t Know What To Write Next… Lessons That Help Children Plan Great Writing [LINK]

Knowledge of sentence structure. Teachers should teach grammar, punctuation, and at the sentence-level through the principles of SRSD instruction. To find out more, see our CPD articles:

- Getting writing instruction right [LINK]

- Guidance on teaching at the sentence-level [LINK]

- The components of effective grammar instruction [LINK]

Craft knowledge. To build up children’s craft knowledge, teachers can use the principles of SRSD instruction to teach children about figurative language, rhetorical devices and other authorial craft moves. To find out more, see our publication: The Big Book Of Writing Mini-Lessons: Lessons That Teach Powerful Craft Knowledge For 3-11 Year Olds [LINK]

To support English language learners, you can invite them to create dual-language texts and engage in translanguaging practices (translanguaging is the practice of using multiple languages fluidly within your writing). To find out more, see our publication: A Teacher’s Guide To Writing With Multilingual Children [LINK].

Finally, to help children develop their own unique writer identity, style, and voice, schools should read our Writing Realities Framework and think about how they can implement its recommendations. You can download it for free here.

Vocabulary. Teachers can put aside instructional time at the editing stage of a class writing project for children to review their use of vocabulary and look for potential opportunities to use synonyms. In addition, teachers can teach functional grammar lessons at the word level (for example, discussing their choice of nouns, verbs and adjectives). To find out more, see our publications:

- No More: ‘My Pupils Can’t Edit!’ A Whole-School Approach To Developing Proof-Readers [LINK]

- Grammar Mini-Lessons For 3-11 Year Olds [LINK]

In addition, schools should ensure that they are developing children’s vocabulary in the wider curriculum subjects and through their reading.

Writing Fluency

To develop children’s writing fluency, school leaders and writing coordinators should ensure that there is a clear progression from EYFS through to LKS2. This is achieved by first accepting children’s emergent writing practices as a temporary scaffold when they first arrive at school. Children are weaned off such practices through daily phonics instruction, handwriting instruction, and by teaching children key encoding strategies. Throughout their time in the EYFS and KS1, children should be invited to use and apply these strategies every day during dedicated writing time. It’s through this daily writing time that children also learn to apply foundational sentence-level skills. This kind of systematic, rigorous and daily routine ensures each child between Nursery and Year Two composes thousands of sentences and crafts hundreds of short (and developmentally-appropriate) compositions. In the process, they internalise all the key skills that allow them to write fluently, happily and accurately. To find out more, download our CPD articles:

- How do we develop writing fluency? [LINK]

- Building up to extended writing projects [LINK]

- No more: ‘They don’t know what a sentence is!’ intervention projects [LINK]

Indirect Cognitive Skills

Intimation is the writerly technique of suggesting or hinting at ideas, details, or meanings without explicitly stating them. When teachers comment that certain pupils show a ‘flair’ for writing, it is often because of their ability to use intimation techniques. To help children develop these skills, we can teach them authorial craft moves through the principles of SRSD instruction. To find out more, see our publication: The Big Book Of Writing Mini-Lessons: Lessons That Teach Powerful Craft Knowledge For 3-11 Year Olds [LINK]

Perspective-taking. Perspective-taking involves being able to take on another person’s point of view – for example, trying to understand what your readers’ reactions might be to your text. Teachers can help children receive others’ perspectives on their writing by ensuring there is a daily routine of class sharing and undertaking regular Author’s Chair sessions with their class [LINK].

Alternatively, perspective-taking in narrative writing might mean sharing how a character is feeling at certain moments in a story. Teachers can actively teach writerly techniques authors use to consider their characters’ perspectives. A number of these techniques can be found in our publication: The Big Book Of Writing Mini-Lessons: Lessons That Teach Powerful Craft Knowledge For 3-11 Year Olds [LINK]

Finally, at the beginning of a new class writing project, teacher and children should take some time to discuss the publishing goal for the project. This should include discussion around what they think their readers’ needs are. To help support such discussion, classes can ‘fill in the GAP’. To find out more, see the following CPD article:

- Establishing publishing goals for class writing projects [LINK]

Planning and monitoring. To help support children’s ability to achieve writing goals, monitor their progress, and reduce cognitive load, teachers can plan their writing units so that they (1) teach the writing processes, (2) set daily process goals. These are probably the two most effective things a teacher of writing can do to improve children’s competency. To find out more, see the following CPD articles:

- The components of an effective writing unit [LINK]

- The components of an effective writing lesson [LINK]

- Trust the process: setting process goals [LINK]

- How we can support children as they are writing [LINK]

Teachers should also ensure children are given plenty of time to develop (and receive verbal feedback on) their writing plans. For more, see the following CPD articles:

- Teaching children how to plan their writing in the EYFS and KS1 [LINK]

- Teaching children how to plan their writing in KS2 [LINK]

- Using focus groups to teach writing [LINK]

Finally, teachers should employ further scaffolds for children who need them. We can recommend looking up suitable scaffolds in our reference book: Supporting Children With SEND To Be Great Writers: A Guide For Teachers And SENCOS [LINK]. Despite its title, this book is useful for supporting any child with writing difficulties. You simply look up the aspect of writing that your class (or an individual child) is struggling with most, and there will be a host of research-based scaffolds and strategies waiting for you.

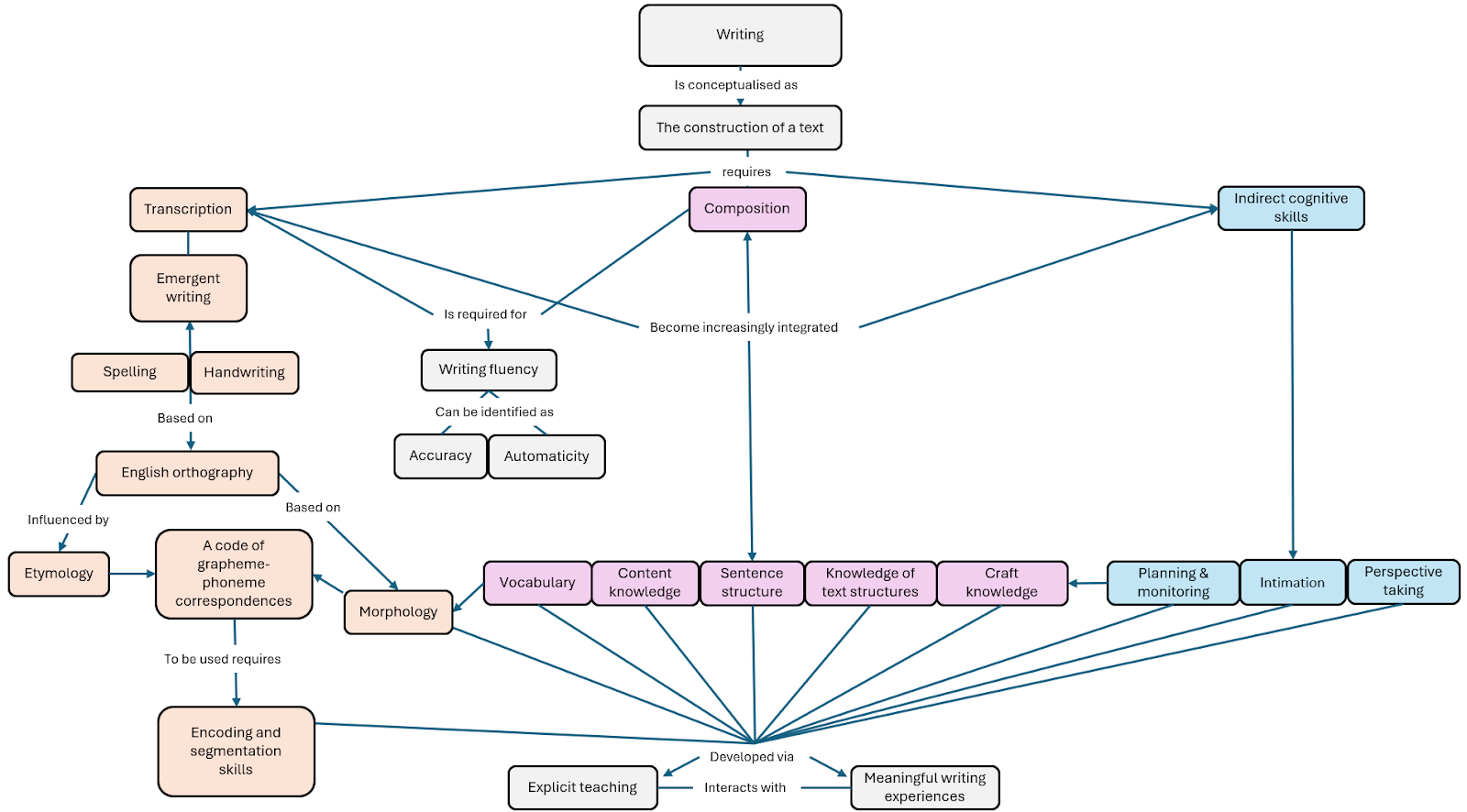

Explicit Teaching & Meaningful Writing Experiences

Transcription, composition and cognitive skills are developed via:

- Explicit teaching.

- Meaningful writing experiences.

These interact with one another. Children use and apply what they learn from explicit teaching when undertaking meaningful writing opportunities. Because children are undertaking meaningful writing experiences, they become increasingly interested in your explicit teaching.

Let’s start with explicit teaching. One of the most validated things a teacher can do to improve their writing teaching is to deliver their instruction through the principles of SRSD instruction (which stands for: self-regulated strategy development). SRSD instruction has been shown to significantly improve the writing of all writers, including those with learning disabilities [LINK]. The beauty of SRSD instruction is that you can use it to teach ‘craft knowledge’ [LINK], sentence-level strategies [LINK], grammatical features [LINK], planning techniques [LINK], revision strategies [LINK] and proofreading [LINK].

Here’s how SRSD instruction typically works:

| Step One: | Orientate Remind the children of the class writing project they are currently working on. This includes checking they know what they are writing and who they are writing it for. |

| Step Two: | Discuss Introduce the craft move you want the children to try out in writing time today. Give the craft move a name. For example ‘show don’t tell’. Then be a salesperson. Tell your class why this craft move is so fantastic and how its use could transform their writing. Link the craft move to the class’ success criteria for the writing project. For example: ‘show don’t tell’ is going to help us achieve ‘share your characters’ feelings’, which is one of our success criteria. |

| Step Three: | Share Models or Model Live Share models. Show children examples of where other writers have used this craft move in their writing. There should certainly be an example of where you’ve used the craft move in your own writing. You should also show examples from other recreational or commercial authors and/or from previous students’ writing. Invite children to ask you questions. Or Model using the craft move live in front of your class. Share some of the writing you are currently working on and show how you’re going to use the craft move to enhance your writing. Invite children to ask you questions. |

| Step Four: | Provide Information We always recommend turning your instruction into a poster or resource which the children can refer to throughout writing time. This helps them memorise the craft move and any conventions it might involve. For example, you might make a poster to accompany a lesson on punctuating speech. The poster can almost always be pre-prepared to save time and can remain up in the classroom over many days, weeks or even months! Children will be showing independent, self-regulating behaviour every time they consult the poster. |

| Step Five: | Invite Invite children to use the technique during that day’s writing time. Monitor children’s use of the craft move during your daily pupil-conferencing. Sometimes you might feel you want your children to practise the strategy prior to using it in their own writing. However, in all honesty, we find this is rarely necessary. |

| Step Six: | Evaluate You can invite children to share how they used the craft move in their writing during class sharing and Author’s Chair. If you have noticed a student who has used the craft move in a particularly powerful, innovative or sophisticated way during your pupil-conferencing, you should invite that child to share their writing with the class. The class can then discuss their friend’s writing and its impact. |

It’s important to remember that the stages shared above constitute a good guide. However, teachers should also feel free to experiment with them if they want to. The professional judgement made by a particular teacher might be that a certain stage could be omitted altogether and that another stage might need more time devoted to it. For example, some teachers like children to practise the taught craft move prior to using it in their own writing, while others find this an unnecessary distraction. Some like to model the craft move live, and create their poster in front of their class, while others like to have made their poster prior to the lesson, or to share writing they have already crafted.

It can be useful to compare SRSD instruction with The Gradual Release Of Responsibility model for instruction (Pearson & Gallagher 1983). We hope that teachers notice how writing instruction can be delivered and then applied, in context, by children every day.

- I did or I do – The teacher either shares how they’ve used the craft move or models how to use it live.

- We do – The class is invited to use and apply the craft move to their own writing that day.

- You do – Children understand the value of the craft move and so continue to use it in their future writing.

I, We & You sits in stark contrast to the ineffective but common habit of ‘front loading’ writing instruction at the beginning of a writing unit and proceeding to ‘cross your fingers’ in the hope that the children will remember everything you’ve tried to teach them. This kind of practice doesn’t help children to write well.

Another thing to like about SRSD instruction is how it naturally links explicit teaching to meaningful writing experiences. Children are expected to use and apply what they learnt that day to real composition. This is important because explicit instruction and meaningful writing experiences need to interact with one another. Children use and apply what they learn from explicit teaching when undertaking meaningful (and developmentally appropriate) writing opportunities.

Let’s talk about meaningful writing experiences. We know that to build a successful writing classroom, teachers must establish:

- A community of writers.

- Purposeful and authentic class writing projects.

- Writing goals that their class needs to achieve.

Children need to know why they are in the writing class. What is their reason for being there? Writers are moved to write in many ways and these purposes for writing provide a great way for teachers to organise meaningful class writing projects across the year(s).

To support school leaders, we suggest they carefully sequence class writing projects across a pupil’s time in school and ensure that they get to attend to these different purposes for writing in ways that are developmentally appropriate. Ultimately, a writing classroom’s goal is to foster a collective engagement in writing while producing manuscripts which align with the curriculum and resonate meaningfully with their intended audiences.

Beyond whole-class writing projects, children need to be given time and opportunity to pursue their own personal writing projects – both at school and at home.

For more on developing meaningful writing experiences, see the following CPD articles:

- Building up to extended writing projects [LINK]

- Articles & resources to help you develop a cohesive approach and progression for writing in your school [LINK]

- Example programme of study and progression documents [LINK]

- A Guide To Personal Writing Projects & Writing Clubs For 3-11 Year Olds [LINK]

- Supporting children writing at home [LINK]

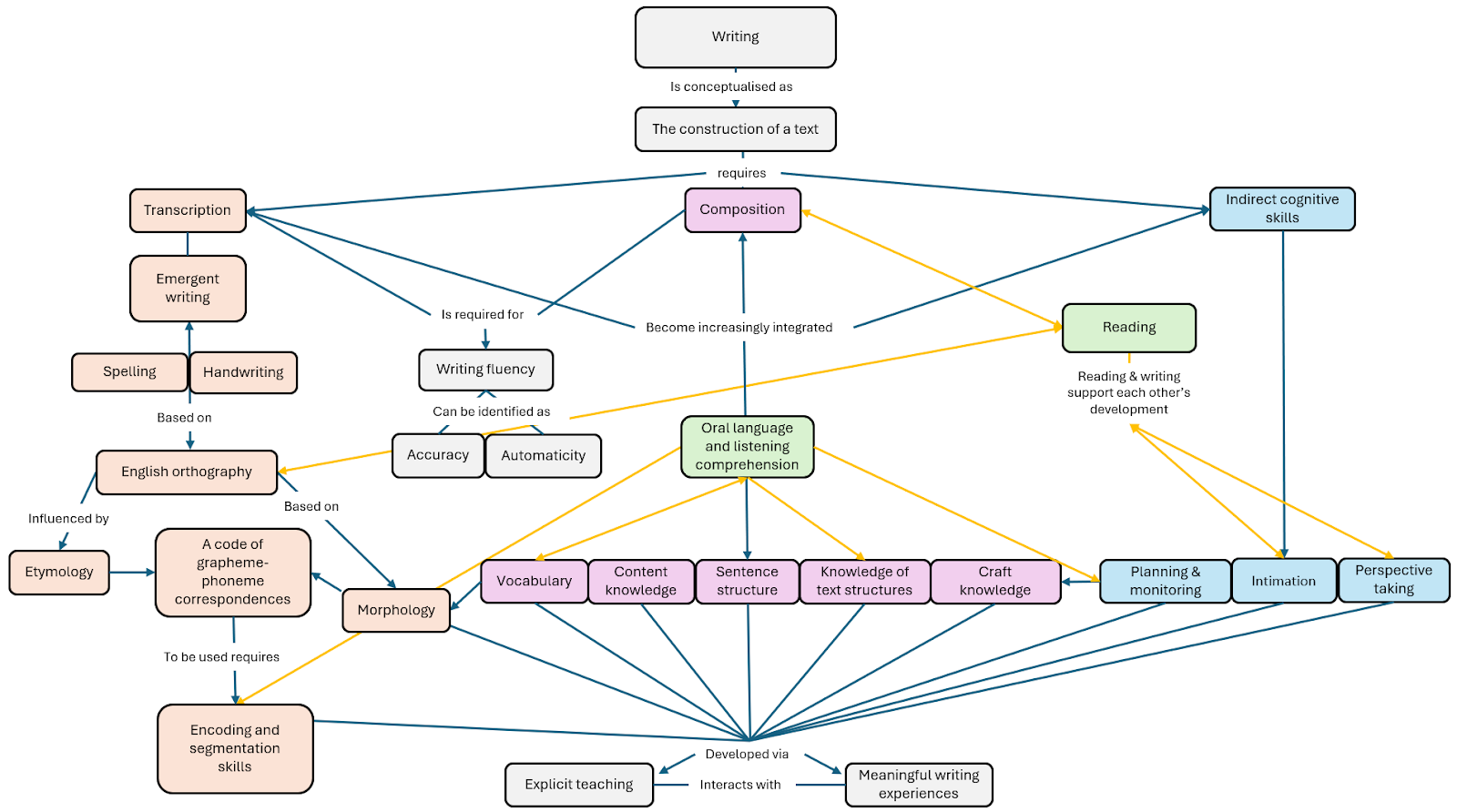

Oral Language

Oral language makes a contribution to aspects of writing that we’ve already discussed. However, there are other things a writing teacher can do to use children’s oral language as a supportive resource. For example, while children are in the process of generating ideas and planning their writing, give them time to talk at a ‘discourse level’. This means letting them tell you and their friends their story prior to writing it. Let me draw out their story and tell it again. Let them act out their story too if they would like! In the context of nonfiction writing, the same applies. Let them discuss their topic and let them draw about it (before explaining their drawings orally to others).

Next, we want to make sure that children are given regular opportunities to re-read or ‘tell’ aloud their texts as they are crafting them. The technique of ‘write a little – share a little’ can be useful here as can Author’s Chair [LINK and LINK for more on these strategies].

Oral rehearsal is also something that will need to explicitly modelled to children. This is the idea that we sometimes translate phrases and sentences out loud to ourselves prior to transcribing them down. If you can link this to drawing too, then all the better. This is why picturebook making in the EYFS and KS1 is such a powerful teaching strategy as we can teach children to (1) ‘make a drawing’, (2) ‘tell their drawing’ and (3) ‘write a sentence about your drawing’. The last action can obviously be changed depending on the children you’re working with. For example: ‘write a word’ or ‘write a paragraph’. For more on this, see our publication: Getting Children Up & Running As Writers [LINK] and our CPD article: Building up to extended writing projects [LINK].

For free CPD articles on utilising and developing children’s oral language in the writing classroom, see the following:

- Developing children’s talk for writing [LINK]

- Friends and authors: The benefits of children co-authoring [LINK]

- Dialogic writing. How to support peer feedback conversations [LINK]

- A quick guide to class sharing and Author’s Chair [LINK]

The Reading-Writing Connection

Reading and writing support each other’s development by:

- Understanding and analysing mentor texts (these are texts which realistically match the kind of writing children are trying to produce for themselves).

- Reading, recognising and using typical text structures and genre features in their own writing.

- Reading can help children generate and develop their own writing ideas (this process is called intertextuality).

- Regularly rereading their text as they go.

For more on this, download our publication: Reading In The Writing Classroom: A Guide To Finding, Writing And Using Mentor Texts With Your Class [LINK]

Reading comprehension development supports children’s:

- Vocabulary.

- Knowledge of sentence structures.

- Knowledge of text structures.

- Craft knowledge.

- Content knowledge (For example, when they are asked to write about their reading in reading lessons. This also includes reading and writing about their learning in the wider curriculum subjects).

- Intimation.

- Perspective-taking.

Decoding mutually supports children’s ability to encode (transcribe the sounds they hear in the words they want to write).

For free CPD articles on the subject of the reading-writing connection, see the following:

- What does the research say about reading in writing lessons? [LINK]

- What is a high-quality text in the context of the writing classroom? [LINK]

- Intertextuality. The glue that binds reading for pleasure and writing for pleasure together? [LINK]

- Reading different types of fiction in the writing classroom [LINK]

- Reading different types of nonfiction in the writing classroom [LINK]

Motivation

Motivation matters. When students are motivated to write, they pay more attention, put in more effort, persist for longer, and are able to write more independently.

Motivated writers bring care and commitment to their writing. Motivating writing teaching is by its definition effective teaching. Children who receive such practice are more likely to learn more.

When pupils lack writing motivation, they get distracted more easily, they do the bare minimum to get by, they avoid taking any risks that might make their writing more successful, they require constant cajoling and policing to stay on track, and they retain very little of what they learn.

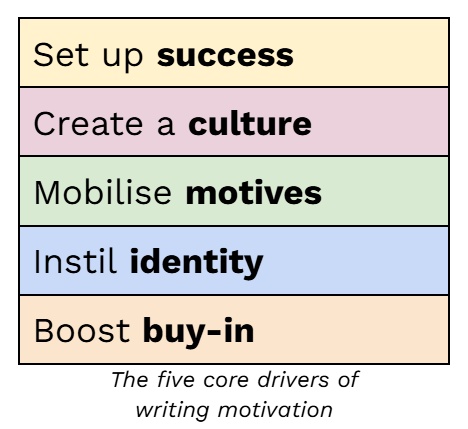

Influenced by Peps Mccrea’s writings on motivation, we produced our own book entitled: Motivating Writing Teaching [LINK]. The chapters of the book are organised around five core drivers of writing motivation.

- The first is success. One of the best ways to boost children’s motivation is to teach them well. This is about teaching in such a way that we can give students confidence that they will be successful.

- Next is culture. This is social in nature. It’s about how the attitudes, routines and actions of the classroom and school environment influence pupils’ view of writing and being a writer.

- Then we have motives. This is about students locating what is moving them to write and why they are bothering.

- After, we have identity. This is about building up a bank of positive past experiences with being a writer. Linked to this identity is a student’s self-concept and their long-standing writerly self-esteem.

- Finally, we have buy-in. This is how we can attend to students’ interests, preferences, and provide them with a sense of choice and control.

Together, these drivers provide a framework for action that all teachers can use to build pupils’ writing motivation. In our book, we take the best of motivational psychology and match it beautifully to evidence-informed teaching practices.

Social & Cultural Development: Building A Community Of Writers

Writers develop through individual cognitive growth and positive social interactions within a writing community. Being part of a supportive and enthusiastic writing community is essential to children’s writing development.

To find out more, you can access these free CPD articles:

- The writer(s)- within- community model and improving the teaching of writing across a school [LINK]

- Why effective writing instruction requires a writer-teacher [LINK]

- Our Writing Realities framework [LINK]

- Our Children As Writers survey [LINK]

A few years ago, we were lucky enough to travel around England and visit some of the best performing writing teachers in the country. These teachers were experts in creating a community of writers in their classrooms. We wrote about what we observed in our book: Writing For Pleasure: Theory, Research & Practice [LINK].

What now?

While we offer one-off professional development sessions to schools and MATs, and recognise their value in strengthening schools’ conceptual understanding of writing and help them identify areas for improvement, we believe long-term and sustained support is essential for translating this knowledge into effective classroom practice. Most schools we work with ultimately seek more than just theoretical guidance – they want to implement a reassuringly consistent approach to writing teaching that they can adopt, adapt, and use as a foundation for change. In these cases, we typically introduce the theoretical foundations of writing instruction before guiding schools through our Writing For Pleasure approach that balances four key priorities:

- Checking the school’s provision for explicitly teaching encoding, handwriting and spelling.

- Developing children’s writing fluency in the EYFS and KS1.

- Providing opportunities for students to craft purposeful and authentic writing.

- Engaging students and teachers in discussions about writing to deepen their understanding of the craft.

To achieve these priorities, we introduce three core writing structures:

- Short ‘book-making’ projects: Focused intervention projects which build automaticity and accuracy in encoding and support sentence construction and cohesion.

- Reading as writers: Analytical and reflective discussions of mentor texts that help students establish ambitious goals for their own writing.

- Class writing projects: Opportunities for students to generate ideas, plan, draft, revise, proof-read and publish extended pieces of writing.

These structures are not anything complex. They simply make practical the principles of world-class writing teaching [LINK for more on this]. They support teachers while allowing them flexibility for adaptation and ongoing improvement.

Our support also extends far beyond writing lessons. We help schools tackle challenges such as assessment, supporting children with specific writing difficulties, helping English language learners, and fostering a school-wide culture of writer-teachers. The majority of our work with schools can be summarised as follows:

- Providing constructive feedback on schools’ current approach to writing instruction and their writing curriculum, either through online discussions or in-person consultancy.

- Helping classroom teachers and school leaders develop a deeper understanding of writing development so they can make evidence-informed instructional decisions that feel right for their school.

- Outlining our Writing For Pleasure approach so that schools can adopt, adapt, or use it as a foundation for further development.

Finally, we work hard to provide free or very affordable alternatives to our consultancy work. We believe passionately in ensuring that high-quality professional development is accessible to as many teachers as possible.

- Anyone can send us a message via email, Twitter, Facebook or Blue Sky with any questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

- We hear from many schools who have used our website to drive their own CPD. You can access all our free CPD materials here.

- Individual teachers can purchase our eBook How To Teach Writing for £5.95. Schools can purchase a licence for all their staff to gain access for £54.75 [LINK].

- Teachers can purchase an individual licence to our website for £28.50 a year. This gives them access to all our eBooks, unit plans and resources [LINK].

- Schools can purchase a whole-school licence to our website for £400 a year. This gives everyone access to our eBooks, programme of study, assessment guidance, CPD materials, units plans and resources. If you’re a smaller school, get in touch as we may be able to provide you with a discount [LINK].

If you want to get in touch, you can use our contact form or email us: hello@writing4pleasure.com

Ross Young & Felicity Ferguson