The act of teaching writing to children has undergone significant evolution over the centuries. While writing itself is an ancient skill, explicit instruction in how to write, particularly through the lens of ‘the writing processes,’ is a relatively recent pedagogical development¹.

This article explores the history of how teachers have taught children the art and craft of writing before giving advice on how you can do it too.

Early approaches to writing instruction (1800-1960s)

In the 19th century, writing instruction in schools was largely focused on mechanics like penmanship, spelling, grammar, and transcription. Writing was more about accuracy and obedience to conventions than making and sharing meaning, creativity or individual expression.

During this period, teachers rarely emphasised the writing process. Writing was seen primarily as a product (something finished and polished in a single session) rather than as something to be moulded and crafted over time.

In the mid 20th century, educational reformers began to see the value in students expressing their own thoughts through original compositions. However, in this more student-centered model, instruction often lacked a clear structure². Children were simply asked to write but not necessarily taught how to generate ideas, plan, draft, revise, proof-read or publish their manuscripts. This gap set the stage for a more formalised approach to teaching writing.

The Dartmouth Conference and the influence of John Dixon (1960s)

A pivotal moment in the history of writing instruction came with the Dartmouth Conference of 1966 – an international gathering of British and American educators that aimed to redefine the teaching of English. The conference catalysed a shift from formalist, prescriptive models of writing to more dynamic, writer-centred approaches.

British educator and researcher John Dixon published his influential report, Growth Through English, shortly afterward. In it, he argued that writing should not be taught as a fixed body of knowledge or a set of rigid forms, but as a tool for personal growth, meaning-making, and social interaction. Dixon proposed that students develop as writers through:

- Expressing their own experiences, thoughts, knowledge, feelings and ideas

- Engaging in meaningful writing projects

- Writing in a variety of genres and for different audiences

- Reflecting on their language use

Dixon categorised language use into four broad modes – personal, poetic, transactional, and exploratory – each serving different writerly purposes. He emphasised the importance of teacher responsiveness, flexibility, and encouraging student agency.

The Dartmouth movement laid the philosophical and pedagogical foundation for what would become the process writing movement. It framed writing as a developmental act, one rooted in the lived experience of the learner – an idea that would deeply influence writer-teachers like Donald Graves in the decades that followed.

The emergence of the writing processes (1970s–1980s)

The modern concept of ‘the writing processes’ began to take shape in the 1970s and 80s. Influential researchers and educators such as Janet Emig, Linda Flower, John Hayes, Donald Graves and Donald Murray revolutionised writing instruction by promoting a process-oriented approach.

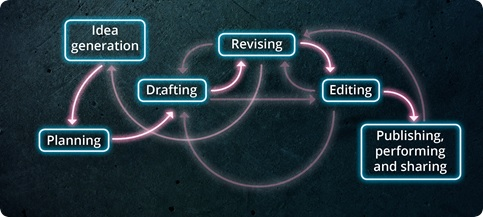

This method emphasised writing as a recursive process with several key stages:

- Generating ideas

- Planning

- Drafting

- Revising (re-seeing, re-envisioning and otherwise reshaping content)

- Proof-reading (checking adherence to conventions, grammar, punctuation, spelling)

- Publishing (sharing with an audience)

Through this framework, students were encouraged to view writing as a tool for thinking, feeling, and communication, rather than merely a writing performance to be judged by the end of a single lesson.

Donald Graves and the birth of process-based writing instruction

One of the most pivotal figures in the development of process-based writing instruction was Donald Graves, whose research in the 1970s-1980s fundamentally changed how teachers approached teaching writing to children.

Graves’ landmark study took place in a New Hampshire elementary school, where he conducted intensive observations of six- and seven-year-olds as they wrote. Using audio recordings, writing samples, classroom observations, and student interviews, Graves sought to understand what young writers actually did when they wrote. His findings were both surprising and transformative.

Graves discovered that even the youngest of children were capable of deep thinking, self-direction, and revision when given time, instruction, agency, and support. He found that children wrote best when they:

- Were supported to choose their own writing topics

- Given time to write their best pieces

- Received consistent instruction and feedback from teachers and peers

- Viewed themselves as real authors with something valuable to say and share

His research culminated in the seminal book Writing: Teachers & Children At Work, which laid out not just his findings but a practical vision for writing instruction. Graves argued that writing should be a daily activity, grounded in real purposes and audiences, and that teachers should serve as fellow writers and instructors – not just evaluators.

The post-process movement: A necessary rethinking

By the 1990s, scholars in composition studies began questioning the dominance of the process model in writing instruction. The so-called post-process movement did not reject the value of the writing process altogether, but it emphasised that writing is far too complex and idiosyncratic to be fully captured in a single, generalised sequence of steps. Post-process theorists argued that there is no single ‘correct’ writing process – different writers use different processes, in different combinations, and at different times, depending on the writerly situation.

For classroom teachers, this post-process movement serves as a reminder that writing is more than a set of steps to follow. It calls for instruction that values diverse writing practices, and emphasises critical thinking about language and purpose.

Modern day

In recent years, studies have built on the foundations laid by Graves and others to offer a more contemporary, evidence-rich model of the writing process approach.

Research evidence continues to deepen our understanding of how children can be taught not only to write, but to think as writers.

While early process models gave some structure to writing instruction, more recent research provides precise, flexible, and effective ways of helping children navigate the complexities of writing³.

Four of the most useful frameworks currently shaping writing pedagogy are:

- The rhetorical situation approach

- Children’s production strategies for writing

- The writing process in the early years

- Ellen Counter’s ‘Writing House’

1. The rhetorical situation approach

A writing classroom, if it is to be authentic, must regularly pursue what’s called rhetorical purpose. This is the idea that writers write because:

- They have something to say

- They have a reason for saying it

- They have someone to say it to

They are moved to write⁴.

This is at the core of what composition, rhetoric, creative writing and journalism courses all call ‘the rhetorical situation’⁵: there is a writer, there is an audience, there is a purpose, and there is a message.

A class writing project therefore begins with a class knowing they have something to say and setting themselves an authentic and purposeful writing goal through which to say it (see LINK for more details). For example: to craft persuasive letters to people in positions of authority, memoirs for loved ones, information texts for their mates, or short stories for the younger children in the school.

Once that intention has been set, teachers and students look outward to high-quality mentor texts that resemble the kind of writing they are looking to produce for themselves. This is reading as a writer: noticing structure, studying grammatical, rhetorical and literary craft moves, analysing authorial voice, and borrowing writerly techniques⁶.

Taken from Reading In The Writing Classroom (Young & Ferguson 2024), here are just some of the things you can look for and discuss as you read as writers:

And here are some of the writerly conversations you might have.

“Children read stories, poems and letters differently when they see these texts as things they themselves could produce.” – Frank Smith

This approach mirrors how writers actually work. While we in no way seek to diminish the importance of children developing as readers, we need to be clear that, in the writing classroom, writing should be the driver for reading. Reading should be in the service of the writers’ goals.

Here is a beautiful representation of what we are talking about. On the display, we can see just some of the high-quality commercial texts children have been reading as part of their fairytale project. In addition, we can see how writer-teachers have shared their own fairytales as mentor texts too. All this rich reading has resulted in the class coming up with their own success criteria for the project: the things they believe they’ll have to do or include to write their own great fairytales too.

In a writing classroom, the act of reading is responsive, deep, and authentic. Children and teachers study texts together because they know it helps them grow as writers. High-quality mentor texts are chosen because they match the class’ writing project (you can see examples here). This is the real apprenticeship of writing. It gives students agency, craft knowledge, and a deep sense of why being a writer matters.

“To learn how to write for newspapers you must read newspapers. For magazines, browse through magazines. To write poetry, read it.” – Frank Smith

For teachers like Sam Creighton, who love reading, such an approach is a dream come true as he finally gets to expose his class to loads of his favourite high-quality texts. Here are just some of the texts he plans to share with his class as part of their memoir writing project.

2. Children’s production strategies for writing

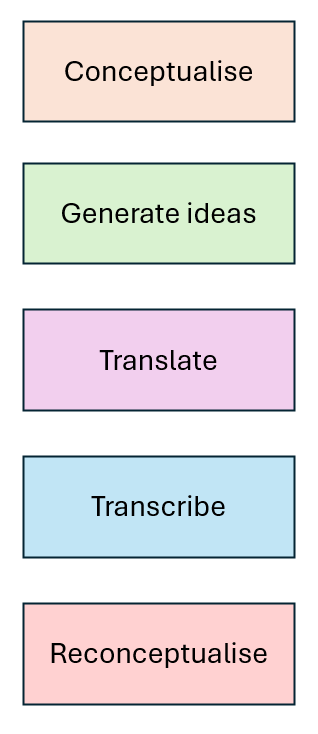

As part of our work devising a conceptual framework for writing teaching, which we called The Writing Map, we described what young writers are doing as they make writing. When a child settles down to write, they will:

Conceptualise As you’ve already read, conceptualising a piece of writing involves establishing the rhetorical situation. Consciously or subconsciously, a young writer will consider the purpose and audience for their writing.

As teachers, we can support children with this. For example, teachers and children, together, can establish a publishing goal for a class writing project [LINK] before reading as writers [LINK].

Generate ideas Next, your young writers will generate ideas of what it is they would like to share with their reader(s). Again, as teachers, we should help and support children by teaching them idea generation techniques that writers actually use [LINK].

Translate This is where your young writers have to convert the ideas they have in their heads into possible phrases and sentences. Teachers can support this process in three ways:

- Ask children to draw their ideas first.

- Invite children to talk about (and otherwise ‘tell’) their drawings with us and their friends.

- Model a planning strategy that we used, before inviting children to use the same strategy for themselves [LINK].

Transcribe Transcription includes attending to letter formation, handwriting (or typing), and spelling. At this point, children must physically make their marks on paper or screen. These skills support children in getting their ideas down in a way that can be read by others, but the accuracy of spelling and handwriting will naturally be variable at this stage. What matters most is that children can record their thinking; refinements to accuracy will be revisited later during the reconceptualise phase.

However, over time, it is important that these transcriptional skills become increasingly fluent and automatic [LINK]. This fluency develops through a balance of regular spelling and handwriting instruction alongside meaningful opportunities to write [LINK].

Reconceptualise This is actually something children are doing all the time. They will regularly stop, think, rethink, draw, redraw, share, discuss, re-read, revise, proof-read and perform their developing compositions. Teachers can support children’s reconceptualisation processes by ensuring that they:

- Have regular moments during writing time to stop and share what they have crafted so far that day. For example, by giving children class sharing and Author’s Chair time [LINK].

- Provide children with explicit revision instruction and revision checklists [LINK].

- Engage in systematic and daily pupil-conferencing with their pupils [LINK].

- Provide ample opportunities and instruction in how to proof-read their manuscripts in preparation for publication or performance [LINK].

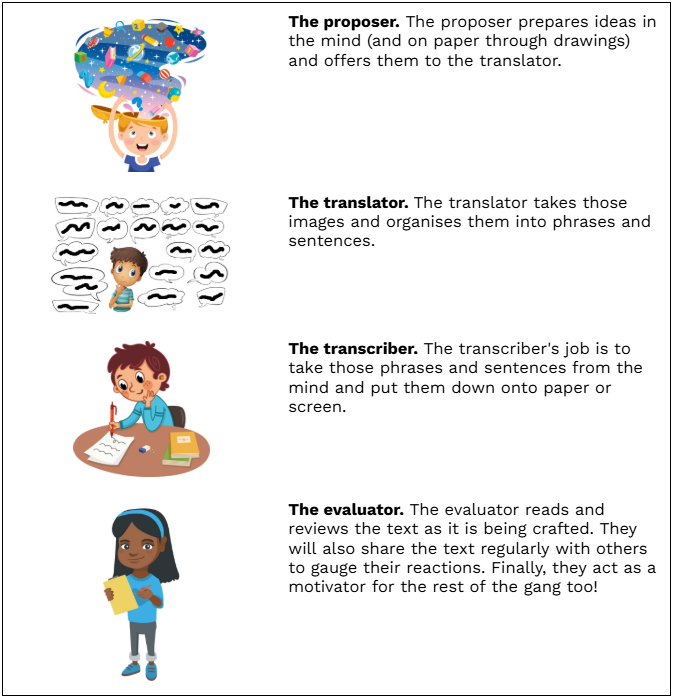

Finally, we can personify the production strategies children use to craft text as if they were being undertaken by different people. In reality, of course, these are done by the individual writer. These people would include:

It’s important to remember that a piece of writing will move between these four people all the time. For example, the evaluator might have to go and talk to the proposer. The translator and transcriber are likely to be in back and forth conversation too.

3. The writing process in the early years

What does the writing process look like for the youngest of children? Well, having observed children writing for a number of years, we’ve noticed that a developmentally appropriate writing process for the EYFS-KS1 looks a little something like this:

We talk At this stage, children are often developing their ideas and translating those ideas through spoken language. Talking helps them to clarify their thinking, play with word choices, and rehearse the structure of what it is they want to say. Children talk their texts into being. As you can see, talk is vital at all parts of a young writer’s process. For example, children talk with one another before they write, as they write and after they write. These interactions occur in different ways and can include:

- Idea explaining Children share what they plan to write about during the session with others.

- Idea sharing Children work in pairs or small ‘clusters’ to co-construct their own texts together.

- Idea spreading One pupil mentions an idea to their group. Children then leapfrog on the idea and create their own texts in response too.

- Supplementary ideas Children hear about a child’s idea, like it, and incorporate it into the text they are already writing.

- Communal text rehearsal Children say out loud what they are about to write – others listen in, comment, offer support or give feedback.

- Personal text rehearsal Children talk to themselves about what they are about to write down. This may include encoding individual words aloud. Other children might listen in, comment, offer support or give feedback.

- Text checking Children tell or read back what they’ve written so far and others listen in, comment, offer support or give feedback.

- Performance Children share their texts with each other as an act of celebration and publication.

We draw Children often like to translate their ideas visually. Drawing allows them to plan and express their thoughts before writing, and it supports their understanding of chronology and narrative sequencing. It also gives them something to talk about and otherwise ‘tell’ prior to transcribing it to paper.

We write Here, children transcribe their ideas into the written form. This may involve mark-making, early letter formation, or structured sentences depending on their stage of development. They apply their phonics knowledge, through encoding, and begin to explore spelling, punctuation, and grammar in context.

We share Children continually share their compositions with others – reading or ‘telling’ aloud or discussing their writing with peers and adults. This stage fosters pride, purpose, and a sense of audience, and it encourages reflection and further development of their writing skills.

This recursive process supports young writers in building both the transcriptionally and compositional aspects of writing in a meaningful and developmentally appropriate way.

4. Ellen Counter’s ‘Writing House’

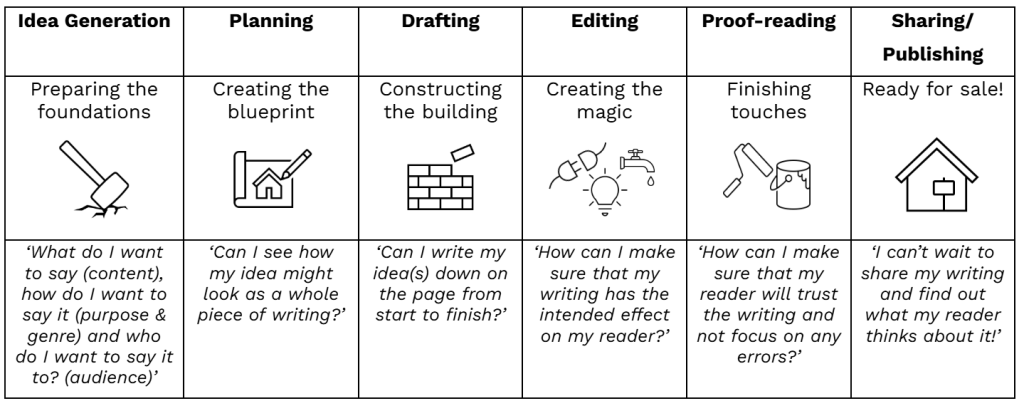

To teach writing effectively, we must encourage children to see writing as a process, while also teaching and modelling strategies that support its key stages: idea generation, planning, drafting, editing, and proofreading.

Whilst the writing process is recursive (we naturally move back and forth between stages), and although it can look different depending on what is being written and why, children need to understand that each stage of the process is distinct and requires a different kind of focus.

We could argue that this process is like building a house. Without time and teaching dedicated to each stage, the writing (like a house) could fall apart and not be fit for purpose. In the same way, our feedback will only be effective if we consider the stage children are at in the process and tailor our advice accordingly⁸.

Using this model, we can extend the metaphor to guide what we focus on during writing time. It all depends on the stage. After all, you wouldn’t insist on ordering paint colours before the walls have even been built. As the DfE’s Writing Framework suggests, it makes little sense to focus on children’s spelling inaccuracies when they are still working hard on getting their ideas down onto the paper⁹.

Figure: A visual representation of the writing process to support shared understanding © HFL Education, used within ESSENTIALWRITING | HFL Education

The terms generate ideas, plan, draft, revise, re-read, evaluate, edit, proof-read, perform and share are all mentioned within the National Curriculum, but teacher training and writing schemes rarely equip teachers with how to explicitly teach these processes.

For example, children are often told to proof-read or ‘check’ their writing without being taught how writers do this, within a clear framework of shared strategies to support them¹⁰.

Take the case of a Year 1 child who was thought to be falling behind in her writing because she wasn’t punctuating her sentences. Interestingly, she:

- Could identify where a full-stop belonged when shown an unpunctuated sentence.

- Had age-appropriate knowledge of sentence structure. For instance, she could read her writing back, recognised where one idea ended, and understood that her reader would need a full-stop before the next idea began.

So what’s happening here?

The issue lies in the misconception and expectation that writing must be 100% accurate at the point of drafting¹¹. The child was only given one shot to get everything ‘right’, so the absence of punctuation is treated as failure. In reality, the problem is we’ve overlooked how writing actually works. Like building a house, writing requires time for each stage: strategies for proof-reading need to be explicitly taught, and space for evaluating and reconceptualising is needed¹⁰. The child wasn’t failing – the approach was failing the child.

Conclusion and next steps

Planning a writing unit

In 2019, we were lucky enough to interview and observe some of the best performing writing teachers in England. We released our findings as a book in 2021. What was clear was how these teachers used the writing processes to plan their class writing units.

Teaching the writing processes is also a validated evidence-based practice, with a potential effect size of +1.28 (for context, anything over +0.4 is considered to be significantly effective).

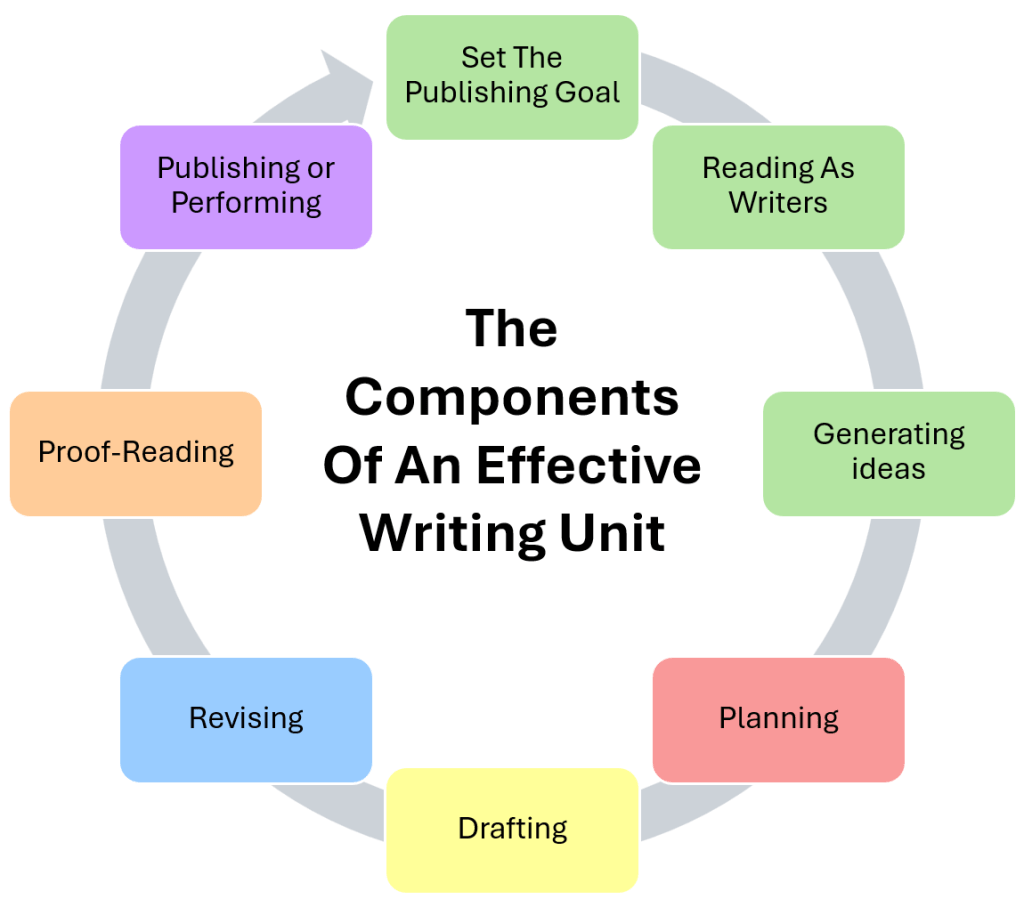

To find out more about the components of an effective writing unit, see our article.

Children also developing their own writing processes

As well as planning effective writing units, the exceptional writing teachers we observed gave their pupils time to develop their own writing process by way of personal writing projects. To find out more, see this publication. In teaching children the writing processes, we do more than guide them to craft great pieces, we hand them the tools to shape their voices, their stories, and, over time, their worlds.

By Ross Young & Ellen Counter

References

- How Writing Works: From the Invention of the Alphabet to the Rise of the Social Media by Dominic Wyse [LINK]

- ‘Teachers’ orientations towards teaching writing and young writers’ [LINK] and ‘Six discourses, four philosophies, one framework: A critical reading of the DfE’s writing guidance’ [LINK]

- The science of teaching primary writing [LINK]

- Motivating writing teaching [LINK]

- The rhetorical situation [LINK]

- ‘Reading like a writer’ [LINK] and ‘Reading in the writing classroom’ [LINK]

- How to teaching writing [LINK]

- A guide to pupil-conferencing with 3-11 year olds: Powerful feedback & responsive teaching that changes writers [LINK]

- The DfE’s Writing Framework [LINK]

- No more: ‘My pupils can’t edit!’ A whole-school approach to developing proof-readers [LINK]

- Debunking edu-myths: Writing errors form bad habits [LINK]