On the 5th of March 2024, Ofsted published its English education subject report: Telling the story. It purports to evaluate the common strengths and weaknesses of English that Ofsted has seen in schools.

The mission of The Writing For Pleasure Centre is to help all young people become passionate and successful writers. As a think tank for exploring what world-class writing teaching is and could be, a crucial part of our work is analysing emerging guidance reports such as the one provided by Ofsted. It is therefore important that we issue a review of what this document has to say.

We will review Ofsted’s report against The Science Of Writing and what we presently know about the fourteen principles of world-class writing teaching (Young & Ferguson 2024). Our review will highlight both the good things shared by Ofsted and also their oversights, and we will provide further exemplification and suggested reading where we think we can add value.

Ofsted’s subject report identifies many of the key cognitive resources The Science Of Writing reports as being essential to children’s writing development. This is good. However, the teaching practices which are subsequently recommended don’t always align with what the research tells us about effective writing teaching. This is particularly true in relation to their recommendations for early writing instruction, and is the most disappointing aspect of the report.

1. Writing fluency

“Primary pupils are not given sufficient teaching and practice to become fluent with transcription (spelling and handwriting) early enough.”

“Pupils are expected to carry out extended writing tasks before they have the required knowledge and skills.”

We appreciate what Ofsted are trying to say here but unfortunately it is clunky and may well be misinterpreted.

✅ Ofsted are right when they say we want children to feel like they can write fluently as quickly as possible and there is a good amount of research on this (Young & Ferguson 2021a, 2022, 2023, 2024; Cabel et al. 2023).

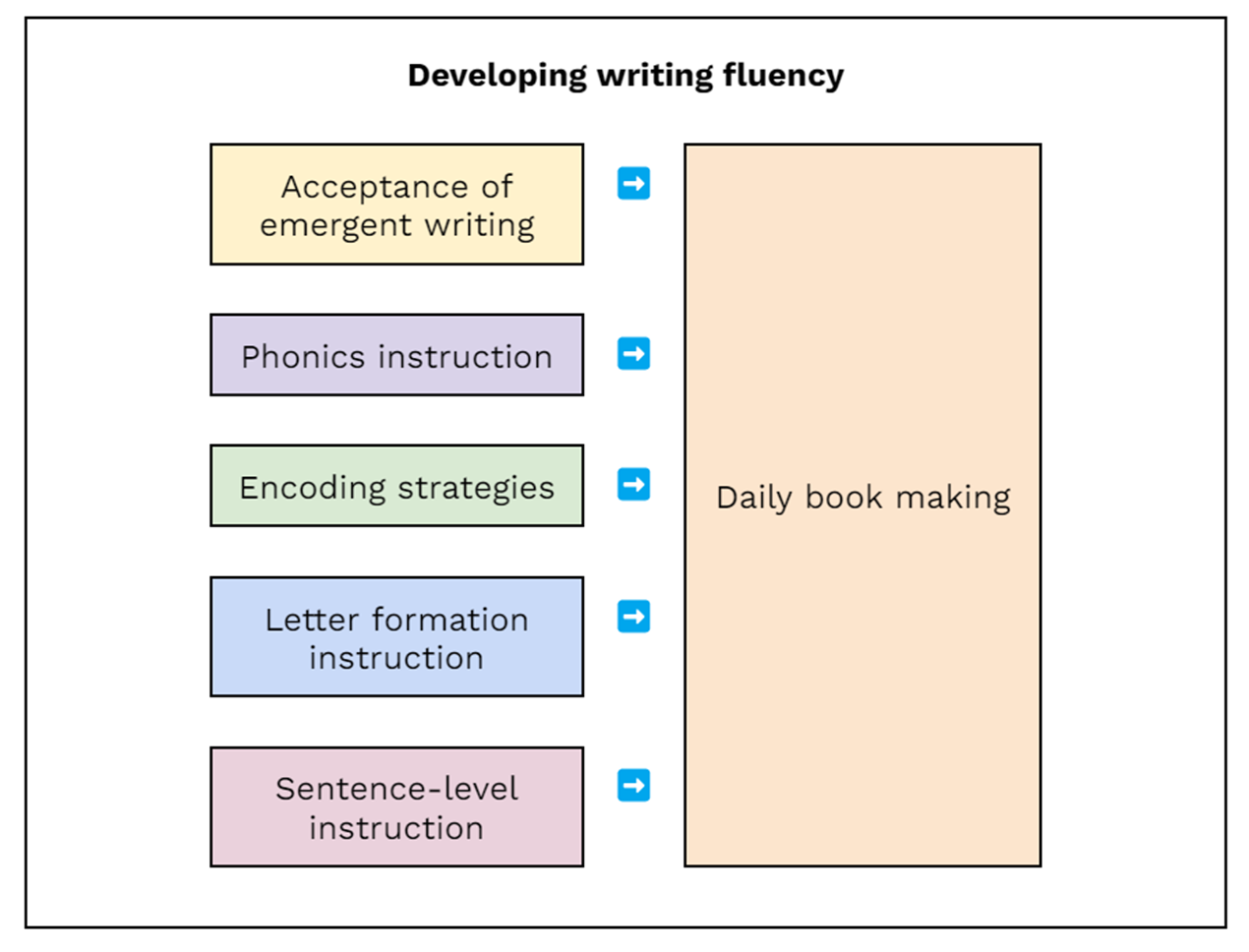

How do we develop writing fluency? [LINK]

❌ However, it’s wrong for Ofsted to suggest that these transcriptional skills should be taught in isolation, away from the craft of authoring. Nor does this foundational knowledge need to be somehow completely mastered before children can be given ‘the right to write stories’. Such a perspective not only goes against research recommendations but is also developmentally unsound. To pursue this recommendation would be an instructional mistake (Young & Ferguson 2022).

Find out more:

- Young, R. Ferguson, F (2023) How do we develop writing fluency? [LINK]

- Young, R., Ferguson, F. (2023) Getting children up and running as writers [LINK]

2. Oral language development

“Oral composition refers to pupils practising composing sentences orally. This helps pupils to develop their knowledge of vocabulary, grammar and sentence structure, and so prepares them for written composition.”

✅ Ofsted are right. We want children to develop their oral language and listening comprehension skills. Indeed, an ability and opportunity to ‘tell’ their writing could have the largest direct effect on the quality of young children’s writing (Kim & Schatschneider 2017).

Find out more:

- Young, R. Ferguson, F (2022) Developing children’s talk for writing [LINK]

- Young, R. Ferguson, F. (2021) How important is talk for writing? [LINK]

- Young, R., Ferguson, F. (2023) Getting children up and running as writers [LINK]

3. Reading mentor texts

“Too often, schools choose texts to study in English lessons based on their link to other curriculum areas, rather than on how they might advance pupils’ knowledge of English language and understanding of literature.”

“Provide opportunities for pupils to draw on the increasingly complex models they study and encounter in their reading.”

“Some schools use high-quality models to help pupils”

✅ Ofsted are right here. We know that there is a profound link between reading and writing. Part of this reading/writing connection is giving children enough time and opportunity to read and discuss ‘mentor texts’ which actually match the kind of writing they are being expected to produce for themselves (Young & Ferguson 2023).

Find out more:

- Young, R. Ferguson, F (2023) Reading in the writing classroom [LINK]

- Young, R. Ferguson, F. (2023) What does the research say about reading in the writing classroom? [LINK]

4. Grammar, sentence structures and punctuation

“Schools teach grammar, sentence structure and punctuation explicitly. However, pupils do not always get enough practice to secure this knowledge.”

✅ We would agree with Ofsted here and would welcome more instructional focus on teaching grammar (Young & Ferguson 2021), sentence structures (Young & Ferguson 2022) and punctuation directly and functionally. This should also include explicitly teaching children how to proof-read (Young & Ferguson 2023).

Find out more:

- Young, R. Ferguson, F (2024) How to teach writing [LINK]

- Young, R., Ferguson (2023) No more: ‘My pupils can’t edit’: A whole-school approach to developing proof-readers [LINK]

- Young, R. Ferguson, F. (2022) The components of an effective sentence-level lesson [LINK]

- Young, R. Ferguson, F. (2023) The components of an effective grammar instruction [LINK]

5. Stop fundamental errors going unnoticed

“Pupils’ books show that fundamental errors go unnoticed and persist over time.”

🟠 We would partially agree with this statement. It’s true that deviations from the conventions their readers would expect to see can regularly go unnoticed in pupils’ books and we don’t want this to happen. Instead, we want teachers and schools to:

- Have a sensible written marking policy (see How To Arrange Your Written Marking in How To Teach Writing – LINK)

- Take the teaching of proof-reading seriously (see No More: ‘My Pupils Can’t Edit’: A Whole-School Approach To Developing Proof-Readers – LINK)

- Provide live verbal feedback and responsive writing teaching daily (see Pupil-Conferencing In The Writing Classroom: Powerful Feedback & Responsive Teaching That Changes Writers – LINK)

However, it’s realistic that such errors will persist over a period of time as this is part of learning. It’s also important to note that even professional writers make fundamental errors with regularity. That’s why some employ professional copy-writers/proof-readers.

6. Organise explicit handwriting and spelling instruction

“Most schools do not give pupils enough teaching and practice to gain high degrees of fluency in spelling and handwriting.”

✅ We would agree with Ofsted here. Disfluent handwriting means children can’t write down all the wonderful things they want to say. Children with poor handwriting can also have lower writerly self-esteem and can consider writing to be a strenuous and difficult activity. If children have to consciously think about their handwriting, they have less cognitive space to focus on other important aspects of quality writing. We also know that a fluent handwriting style improves other aspects of children’s writing (e.g. the quality of their compositions). Finally, and regrettably, teachers have been known to be negatively biassed towards students with poor handwriting when assessing their compositions.

Explicit handwriting instruction guidance:

- A simple and consistent script taught across the school.

- Regular instruction and deliberate practice (5 mins of instruction – 5 mins of practice is a good rule of thumb).

- Children write a small number of letters together at a time (3-5).

- Teachers give feedback and individualised instruction during practice.

- Children should also self-monitor and evaluate their attempts.

- Check children’s posture. Make sure they look comfortable when writing.

- Reiterate what’s been taught when children are publishing their ‘real’ writing.

- The focus should be on legibility, speed and stamina, not adherence to a particular style.

- Additional instruction/intervention for children who need it.

Find out more:

Explicit spelling instruction:

It is suggested that children be exposed to a balanced approach to spelling instruction which includes teaching the following in combination and at the earliest of stages.

- Phonology – relationship between letters (graphemes) and the sounds (phonemes) they represent in spoken language.

- Morphology – the structure and formation of words in a language, including their roots, prefixes, suffixes, and how they combine to create different meanings.

- Orthography – involves teaching children typical rules and patterns for spelling.

- Etymology – studying the origin and history of words.

Children should also be taught how to proofread for their misspelt attempted spellings.

Find out more:

- Adoniou, M. (2014). What should teachers know about spelling?. Literacy, 48(3), 144-154 [LINK]

- Adoniou, M. (2022) Spelling It Out: How Words Work and How to Teach Them Cambridge University Press [LINK]

- The Research On Spelling [LINK]

7. Using time productively

“In some schools, time is not always used productively, most commonly in key stage 1. In these schools, pupils carry out time-filling activities that lack purpose and do not help them to make progress in English.”

🤷🏽 We don’t know if this is true. However, if this feels like it might be the case for you or your school, consider reading the following article: The components of an effective writing lesson [LINK].

8. Explicitly teaching writing

“Schools typically do not provide enough explicit teaching or opportunities for pupils to practise the knowledge and skills that are not yet secure”

✅ We would certainly agree with Ofsted here. The majority of the schools we begin working with tell us that they struggle with how to explicitly teach writing and have instead relied on their reading programmes to teach it. You may wish to read our article: Issues With The Book Planning Approach And How They Can Be Addressed for more details on this – LINK.

Find out more:

- Young, R. Ferguson, F (2024) How to teach writing [LINK]

- Young, R. Ferguson, F. (2022) Getting writing instruction right [LINK]

- Young, R. Ferguson, F. (2023a) Evidence-based writing instruction for children with SEND [LINK]

- Young, R. Ferguson, F. (2023b) Evidence-based writing instruction for 11-18 year olds [LINK]

9. Rushing class writing projects and getting rushed results

“The rush to produce extended pieces of writing independently also means that oral composition appears to be undervalued as a process.”

“Provide opportunities for pupils to write frequently for a range of purposes and audiences. Pupils also need to be taught how to plan, draft and revise their work, to reflect on the choices they make as writers.”

✅ We would certainly agree with Ofsted here. The majority of the schools we begin working with tell us that they find planning writing units very difficult and that there is a pressure for children to produce lots of writing. This makes some sense because we know children do get better at writing by writing. However, teachers also need to plan rigorous and reassuringly consistent class writing projects which give children quality time to engage and learn about all the writing processes. For more information, see the following articles:

- The components of an effective writing unit [LINK]

- Planning a class writing project with the greater-depth standard as the standard [LINK]

10. Not making the link between phonics and encoding for writing

“Pupils’ knowledge of phonics is not always considered when they are asked to read or write in other English lessons.”

✅ We would certainly agree with Ofsted here. This is something we often pick up on when working with colleagues in the EYFS and KS1. Indeed, it feels like the time is now right for Ofsted to move its focus on how phonics can help children with their early reading to focusing on how it can have a transformative impact on children’s encoding skills and their early writing development. It takes a lot of cognitive energy for children to take the phonemes of their speech and present them as graphemes of written language; otherwise called encoding. In the context of writing, phonics instruction should also focus on how to encode and produce ‘sound spellings’ (also known as invented spellings, temporary spellings, own spellings or approximated spellings) and be orientated towards how this instruction will be relevant and useful to the class as writers during their daily writing or ‘book-making time’ (Young & Ferguson 2022). We know that when children receive phonics instruction that also encourages them to produce ‘sound spellings’ when writing for themselves, they outperform those not in receipt of such instruction on a whole variety of writing and reading measures (Rowe 2018).

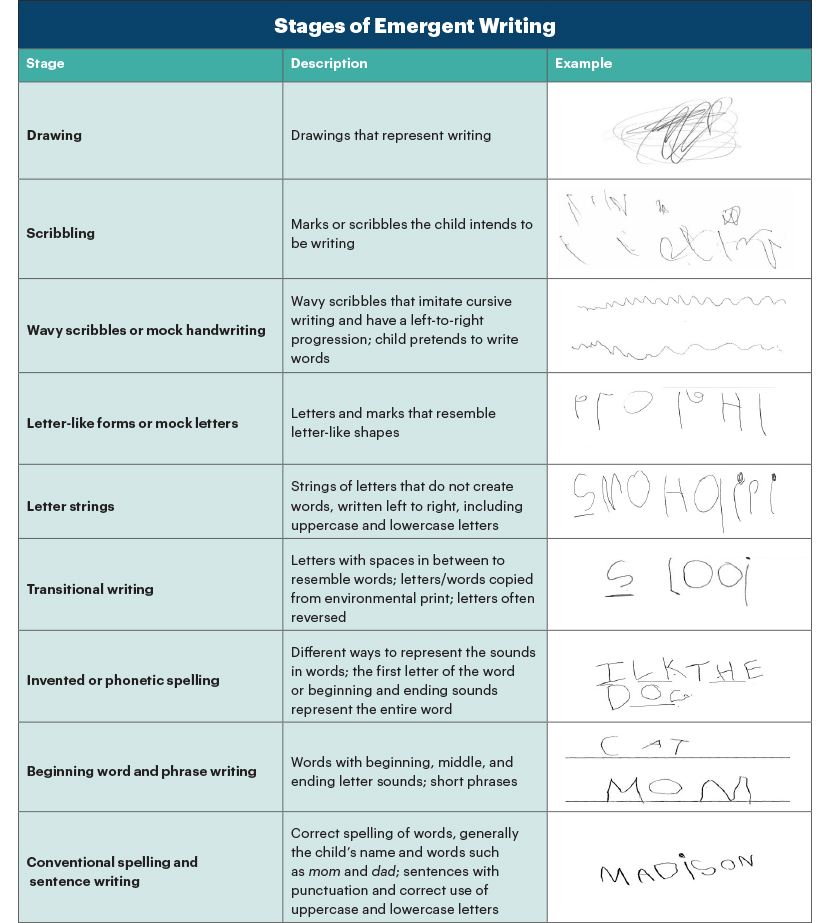

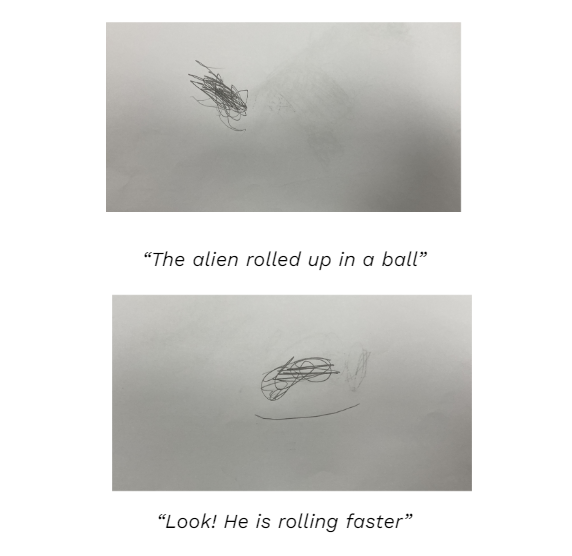

❌ However, one issue with Ofsted’s report is how it insists on children being able to encode before they are allowed to write independently. This suggestion is actually developmentally inappropriate and ultimately reduces young children’s desire to write (Byington & Kim 2017; Gerade et al. 2012; Cabel et al. 2023). This shouldn’t be a recommendation made by Ofsted. Instead, they should have looked at the research around the stages of ‘emergent writing’. This research helps senior leadership teams and teachers understand how children can access writing and being a writer before they’ve learnt to formally encode (Byington & Kim 2017; Young & Ferguson 2022).

The report also fails to mention how children’s letter formation develops through a recursive process of: drawings and scribbles; linear scribbles and mock handwriting and letter-like symbols. This then progresses to: random but real letter strings; letters that represent key sounds learnt; spaces that indicate separation between words; ‘sound spellings’ using phonics knowledge before finally spelling words conventionally. To try and somehow skip these stages would be developmentally inappropriate.

An example of the stages of emergent writing children work through

(Byington & Kim 2017)

11. Children are already ready

“Pupils who are not secure in the foundations of writing are being asked to complete tasks that they are not ready for.”

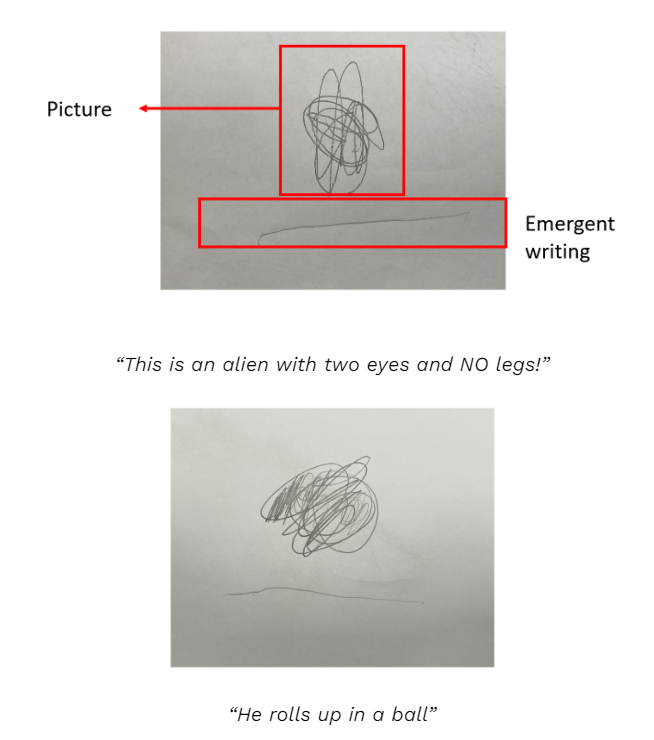

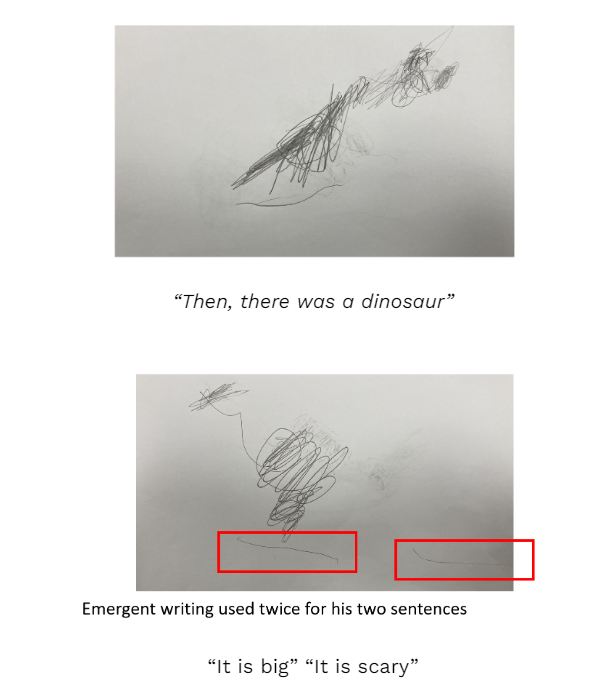

I think we can all agree that making a picturebook is a pretty complex task – just ask any professional children’s author. However, Wyatt has only just arrived in Nursery and has already made one. His school uses the Writing For Pleasure approach to teach writing (Young & Ferguson 2022). This means children learn something about writing every day and they are invited to make books every single day. It is the autumn term and this is one of the first books Wyatt has ever made:

Isn’t that a brilliant story? Wyatt is already ready to write. I should explain that Wyatt is already learning a number of things about book-making. He is learning that a book should have a picture and some emergent writing on every page. He has also learnt that when you are ‘telling’ your book – you should ‘tickle your writing’. This involves moving your finger across your emergent writing so you can tell people what it says. This is how I know what Wyatt’s book says. He was able to ‘read’ it to me – and I privately wrote down what his writing said in my notebook.

If you find this interesting, you might like to download our eBook: Getting Children Up & Running As Writers – LINK.

12. In the writing classroom, encourage children to write about content held in their long-term memory

“To develop proficiency in writing, pupils need… knowledge of the topic they are writing about.”

✅ This is true and we agree with Ofsted. The Science Of Writing identifies content knowledge (what Ofsted call ‘topic knowledge’) as an essential cognitive resource writers need to draw from to write successfully. We know that when children are allowed to choose and access a topic they are familiar with and emotionally connected to, their writing performance improves and they produce higher quality texts (see this article for more details – LINK). This is because they access content which is already stored in their long-term memory, which then allows them to focus on what really matters – crafting the writing. There are a number of ways teachers can help children access rich content knowledge in the writing classroom:

- Explicitly teach idea generation techniques in writing lessons (Young & Ferguson 2022). Idea generation techniques ensure all children are writing using rich and extensive content knowledge.

- Invite children to write about their reading in reading lessons (Young & Ferguson 2020).

- Invite children to write about what they are learning during lessons in the wider curriculum (Young & Ferguson 2020, 2021).

13. Supporting children with SEND to be great writers

“Leaders have the same curriculum ambitions for pupils with SEND as for their peers. In the best examples, this means that curriculum end points are broken down further to give pupils more time to embed knowledge before moving on to more challenging content. Teachers make adaptations, including using further explanations. They modify resources when needed and use appropriate groupings to ensure that pupils can access the content in a suitable sequence. In the weakest examples, pupils are expected to copy from the board or from teaching assistants without fully grasping what they are writing or reading. These schools are not clear about how best to support pupils in the earliest stages of learning to read and write.”

✅ We are really pleased to see Ofsted highlight some evidence-based practices that support children with SEND to develop as great writers. We are also pleased that they highlighted what not to do. Namely, asking children to copy from the board or have a teaching assistant undertake the writing on children’s behalf.

Find out more:

- Young, R., Ferguson, F. (2023) Supporting children with SEND to be great writers: A guide for teachers and SENCOS [LINK]

- Young, R. Ferguson, F. (2023a) Evidence-based writing instruction for children with SEND [LINK]

14. Well done, that school!

“How one primary school went about developing their writing curriculum. Leaders had carefully identified the stages pupils needed to go through to develop their transcription skills. They started with encoding, the reversible aspect of phonics, which pupils practised to fluency. As pupils developed proficiency in writing captions and simple sentences, leaders took a stepped approach to introducing them to different types of sentence structures and grammatical conventions. Pupils were again given the time to practise these before starting to experiment further with the structures. Teachers modelled the component parts, first at word, then sentence, then paragraph level, before moving on to whole text composition later. Although leaders made sure that pupils were introduced to increasingly complex texts for their reading curriculum, they had decided to focus on building secure foundational knowledge and skills in writing. Oral composition continued to play a significant role in English beyond Reception, ensuring that pupils could create complex narratives verbally. Pupils were not rushed into composing complex written compositions before they were ready.”

✅ We were delighted to see such a sensible approach taken to developing children’s early writing. This reflects the recommendations we make to our Writing For Pleasure schools. First, we ask teachers to focus their instructional attention on encouraging children’s emergent writing practices and move onto teaching encoding strategies once their phonics programme is introduced. Children quickly realise that all this instruction is there to serve their daily opportunities to make books. They use and apply their foundational knowledge to make and share meaning with, and for, others. This way, children’s compositional and transcriptional knowledge develops concurrently.

Once encoding is well-established, children start making what we call ‘list books’. These are simple books which match the ‘baby’ or ‘board’ books they should have read prior to coming to school. These list books encourage children to write captions, single words, and/or short phrases. Once children begin to outgrow these projects, teachers move the children onto writing simple picturebooks – with the expectation that children write a single sentence on each page. Children then very naturally move beyond this – writing multiple sentences. Finally, children migrate to making ‘chapter books’ where they write a paragraph or ‘chunk’ of text on each page.

If this sounds interesting to you, and you would like to find out more, download our eBook Getting Children Up & Running As Writers: Lessons For EYFS-KS1 Teachers [LINK].

Summary

What we are really pleased about:

✅ The need to teach writing explicitly is put front and centre in the report [LINK].

✅ There is a focus on developing children’s writing fluency [LINK].

✅ Reiterates the point that phonics instruction should serve children as encoders as well as decoders [LINK].

✅ Oral language development is highlighted as a significant factor in children’s writing success [LINK].

✅ The importance of reading mentor texts is emphasised [LINK].

✅ Teaching grammar and sentence-structures functionally is reiterated [LINK], [LINK], [LINK].

✅ The need for short but regular handwriting and spelling instruction is acknowledged [LINK], [LINK].

✅ The suggestion to stop rushing class writing projects is welcomed [LINK].

✅ Acknowledges that when children can write on topics they are knowledgeable and passionate about, they can focus their attention on producing quality writing [LINK].

✅ Highlights the need to employ evidence-based writing practices for children with SEND [LINK].

✅ Showcases how schools need to have a clear progression for writing development in the EYFS through to the end of KS1 [LINK].

What we are less than thrilled about:

❌ Suggesting that foundational knowledge needs to be somehow mastered before children should be given ‘the right to write’ [LINK].

❌ Not mentioning the importance of accepting and building on children’s emergent writing practices when they first come to school [LINK].

❌ Not accepting that making errors is a part of learning to write.