By Alice Bidder – Hartland International School

How many times have you needed to write a diary from the perspective of an evacuee or a non-chronological report on the Vikings in your life? Most probably, never. However, how often do we need to write a letter to bring about change or engage in writing that explains a process or discusses difficult issues?

This action research project aims to measure the impact of choice on writing motivation in Year 6.

Background of the problem

At Hartland, we felt we needed to remodel our writing curriculum to give the children a clear purpose for writing. Too often we were receiving 26 copies of the same narrative that had been “innovated” from a model text. It lacked creativity and children were not motivated to write. Therefore, we began the journey to improve attitudes to writing through Ross Young and Felicity Ferguson’s Writing for Pleasure framework.

It has long been a challenge to have children write at length in Year 6 and so introducing the element of choice was introduced to combat this. The Writing for Pleasure centre has created a framework for primary writing that puts supporting children’s choices at the heart of the curriculum. New to the role of English lead for the academic year 2024-25, it was a school-wide priority to give both students and teachers alike the opportunity to make changes to their attitudes towards writing.

Literature review

The National Literacy Trust: Children and young people’s writing in 2024, reported on worrying statistics for the state of children’s motivation for writing. In a survey of 76,131 children and young people, fewer than 3 in 10 children (28.7%) reported that they choose to write in their free time. Furthermore, 44.0% of children and young people aged 8 to 18 struggled with deciding what to write, and 1 in 3 (36.8%) admitted that they only wrote when they had to. This further highlights the need to consider curriculum choices when delivering writing lessons to pupils. As teachers, we have a duty to inspire children’s writing ideas and provide support with this process when needed.

In the academic year 2023/24, 72% of children met the standard for writing in teacher assessments (DfE 2025). This is a decline of 6% since before the pandemic in 2020. Additionally, students achieving greater depth remained at 13%. Another decrease, down from 20% before the pandemic. These statistics demonstrate the rapid decline in outcomes for writing in the United Kingdom. Curriculum design over the last decade has been catered towards ‘cross-curricular learning’. Often, history and geography content is taught through English lessons and so writing instruction can be secondary to exploring texts that are didactic to the curriculum topics (Young & Ferguson 2021).

Methodology

The action research approach to measure the impact of choice in writing was necessary as it is important to review practice regularly and make changes to achieve maximum impact. It is also important to reflect and review each action research cycle to understand what methods are not providing impact and so should be revised before the next cycle.

In this research, this took the form of a new writing project every 6-8 weeks. At each milestone, outcomes for writing were assessed and where students had been successful, their writing choices were analysed to depict why this was. The study aimed to answer three questions:

- Does supporting children’s writing choices impact their writing motivation?

- Does supporting children’s writing choices impact their writing enjoyment?

- Does supporting children’s writing choices impact their identities as writers?

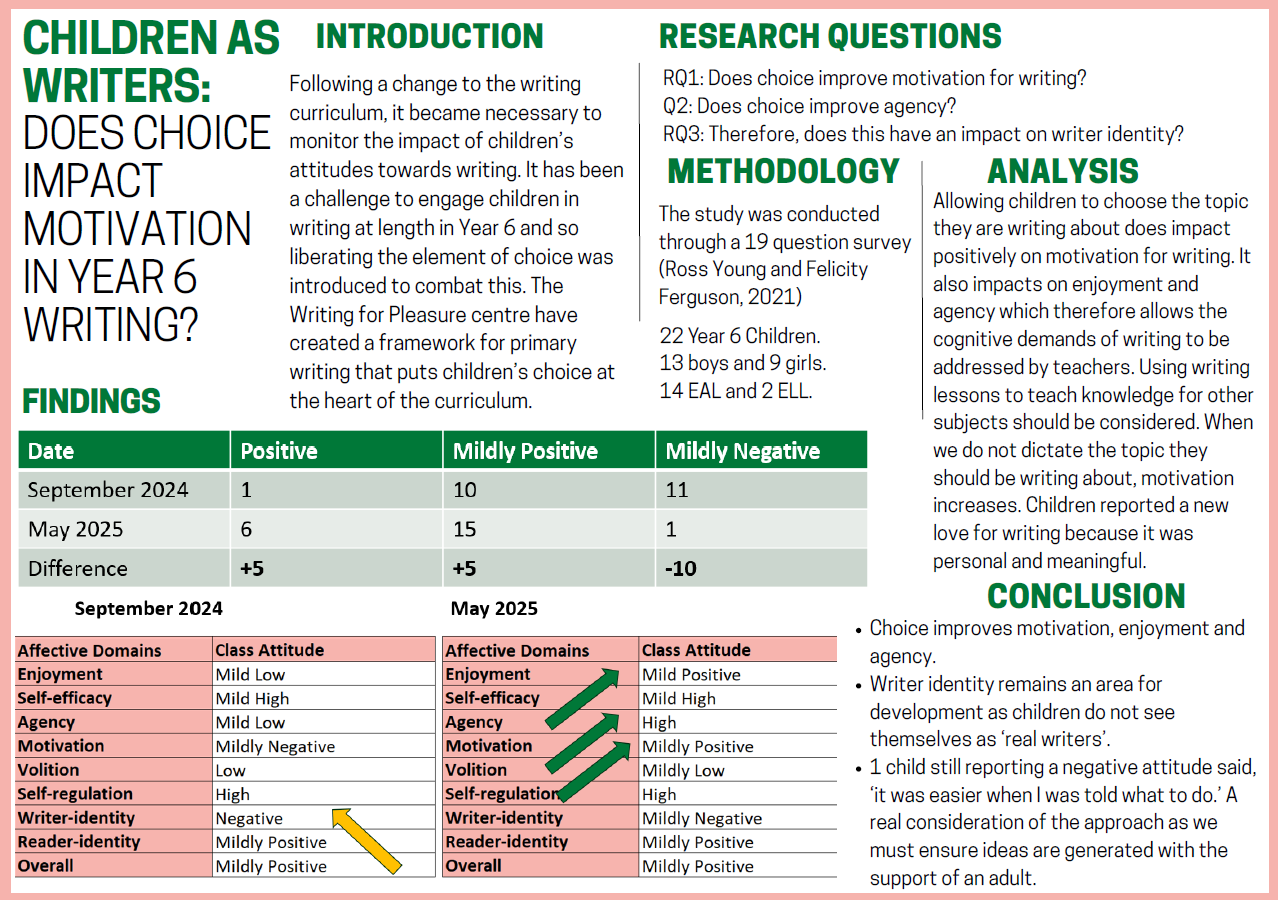

The research began with a Children As Writers survey. All children completed the survey of 19 questions, each written to measure one of the affective domains of writing (Table 1). This was then reviewed in May 2025 with a final measure of the affective domains (Table 2). Student interviews were conducted in May 2025 to further understand a small percentage of the outcomes.

- Participants: The sample included 22 students. 13 boys and 9 girls from a Year 6 class in an International, British Curriculum school in Dubai.

- Data Collection: 22 students completed a survey in September 2024 and then repeated the same survey in May 2025. 1 student interview was conducted in May 2025.

Data analysis

In September 2024, children, as a collective, reported ‘mild low’ enjoyment, ‘mildly negative’ motivation and ‘mild low’ agency (Table 1). This showed that children did not have a positive outlook on writing, were not motivated to write and felt that they did not have ownership over their writing. As Year 6 children, aged 10-11, attitudes towards writing are often challenging to change as they have spent six years at primary school and have the most experience with the subject. Therefore, the results of the survey were not surprising at this stage.

Table 1: Outcomes of the ‘Children As Writers’ survey in September 2024.

The aim of the survey was to focus on enjoyment, motivation and writer-identity. This is because motivation in particular is linked to increased persistence, attention and effort (Young 2024). These behaviours are also related to how children manage the cognitive load of writing (Young & Ferguson 2023).

Attainment outcomes in writing for the class suggest that 79% are meeting the expected standard and 71% achieving above the standard. Whilst this is significantly above outcomes reported in the United Kingdom, the assessment framework used was not the same criteria. The Knowledge and Human Development Association (KHDA) is the governing body for Dubai and the assessment framework used reflects the demands of the country.

However, it is possible to compare the 79% meeting the standard as a reflection of the success of the writing curriculum as this is above the 72% meeting the standard in the United Kingdom. Although the aim of the study was not to measure attainment in writing, it is interesting to note the outcomes do not drop when supporting pupils to choose their own writing ideas.

When the survey was replicated in May 2025, results showed a positive increase in all the affective domains. Significantly, enjoyment and motivation. Whilst the domain of writer-identity has increased from ‘negative’ it remains ‘mildly negative’ from student’s final responses. When questioned about this, children reported ‘real writers are published authors, not children’. Therefore, this will continue as a priority next academic year.

Teachers should strive to work on children’s opinion of themselves as writers and engage with them as ‘real’ authors to demonstrate that the writing process is the same for them as it is for recreational or professional adult writers.

Table 2: Outcomes of the ‘Children As Writers’ survey in May 2025.

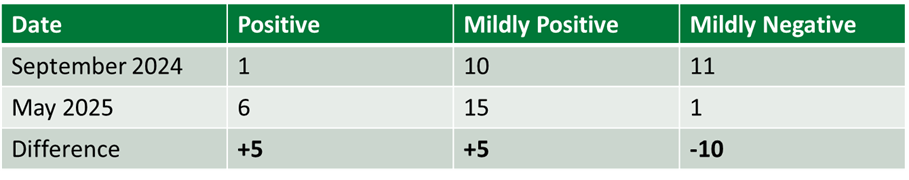

On an individual basis, the survey also reported an overall attitude to writing based on a five level scale: negative, mild negative, mild positive, positive and very positive. In the initial survey, 1 student had a positive attitude towards writing. 10 were mildly positive and 11 were mildly negative. This culminated in a 50% negative outlook and 50% positive. After a year of using the ‘Writing for Pleasure’ framework and giving children choice in their writing lessons, 6 children reported a positive attitude (23% increase), 15 were mildly positive (23% increase) and 1 remained mildly negative (45% decrease).

Table 3: Individual outcomes of the survey with differences shown.

Results

- Research question 1: Does supporting student choice improve children’s motivation to write?

Yes, in the context of the children in the sample.

- Research question 2: Does supporting student choice improve children’s writing enjoyment?

Yes, in the context of the children in the sample.

- Research question 3: Does supporting student choice improve children’s writer-identities?

Not to a positive level, yet.

Discussion and reflection

When comparing the findings of the study to the literature available, it can be said that supporting children to make their own writing choices improves their motivation, enjoyment and agency as young writers. This is an issue that is being felt in the international school systems as well as in the United Kingdom. A simple change in teacher practice should be to involve children in the idea generation stage of a class writing project. If children are being dictated to about the topic they must write about, we cannot hope for improved motivation for writing both in and outside of the classroom (Young & Ferguson 2021). Teachers should reflect on how weighted their English curriculums are towards other subjects as opposed to explicitly focusing on the teaching of writing. For example, are their writing curriculums simply a supplement for their reading or wider-curriculum subjects (history/geography)? If they want to improve the attitudes of their students and their writing outcomes, they might need to think again.

On a personal level, my practice has improved as I have reflected on each writing cycle to continually take children’s voices into account when planning a unit. Explicitly modelling and teaching children idea generation strategies as part of the sequence has improved in each iteration. I have also had time to reflect on the successful pieces of writing as well as asked children what I could have done differently. When planning lessons to support children with coming up with their own ideas, I started quite open and free as I thought this would be the best approach. However, when I was met with a sea of blank faces and a chorus of ‘I don’t know’, I knew that idea generation techniques have to be explicitly taught and modelled if we are going to support pupils. We developed lessons from Young and Ferguson’s materials to teach the ‘I am an expert’ and ‘Let’s have an ideas party’ techniques.

It was important to engage with the advice with the authors of the framework that stated, ‘giving children choice doesn’t mean you can’t give advice or direction’ (Young & Ferguson 2025). This statement is further supported by additional advice for staff: ‘teachers can be direct and tell children to choose something else – as long as they can explain to the child why’. This highlights the important role that the teacher has at this stage in the writing process to ensure that children’s ideas will be fruitful and beneficial to their progress as a writer. We must provide children with the confidence that their ideas matter and other people will be interested in reading their writing.

The introduction of ‘faction’ (a blend of facts and fiction) has also been an important element to our lessons and curriculum. This teaches children that writing lessons are not always about regurgitating facts and curriculum content but about teaching them the skills to become great writers. It does not matter if ‘the facts’ in their faction writing are true. The beauty of faction is that children get to invent their own facts whilst focusing on the objectives of the writing curriculum and developing their authorial voice.

All teachers at Hartland have followed this approach for the academic year. This will continue indefinitely as we feel, across the school, children’s motivation has greatly improved. Next year, teachers in all year groups will carry out the Children As Writers survey with their classes at the beginning and end of the year. In its initial phase, this will give teachers an understanding of their classes’ current attitude and give them clear next steps on which domains need to be addressed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, choice has an impact on motivation and enjoyment of writing. Teachers should reflect on their current writing curriculum and aim to involve children in the process. Their ideas should be at the heart of their writing during writing lessons and teachers should focus on explicitly teaching writing skills rather than delivering content for other subjects. Writing lessons must be carefully planned and student choice should not be interpreted as providing a lack of direction.