Developing the youngest of writers is a multifaceted process, influenced by the interplay between transcription (the mechanical aspects of writing) and composition (the generation and sharing of ideas).

Research from the past few decades would suggest a centralist (sensible) approach to teaching early writing [LINK]. An approach which includes a focus on teaching emergent writing, transcription and composition. An approach that acknowledges the need for foundational transcription skills while also fostering children’s communicative competence. A nuanced integration of these elements creates an environment in which children develop both the technical fluency necessary for writing and the cognitive flexibility to engage in developmentally appropriate writing projects [LINK and LINK].

Start With Emergent Writing

Emergent writing is the early writing that all children bring to school. Developed through experimentation and exploration, it progresses through stages of scribbling and attempts at letter formation before evolving into conventional words and sentences.

(Byington & Kim 2017)

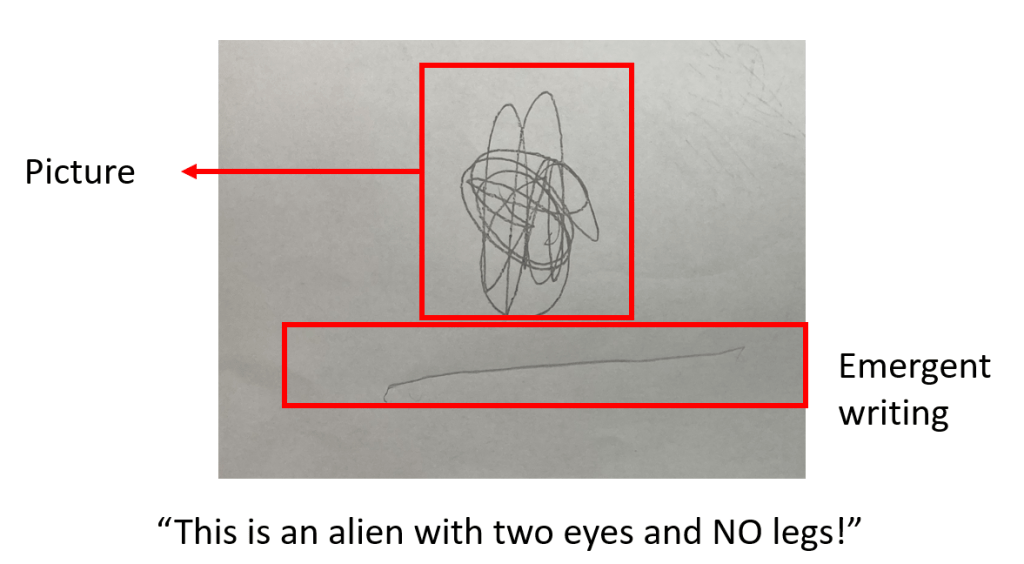

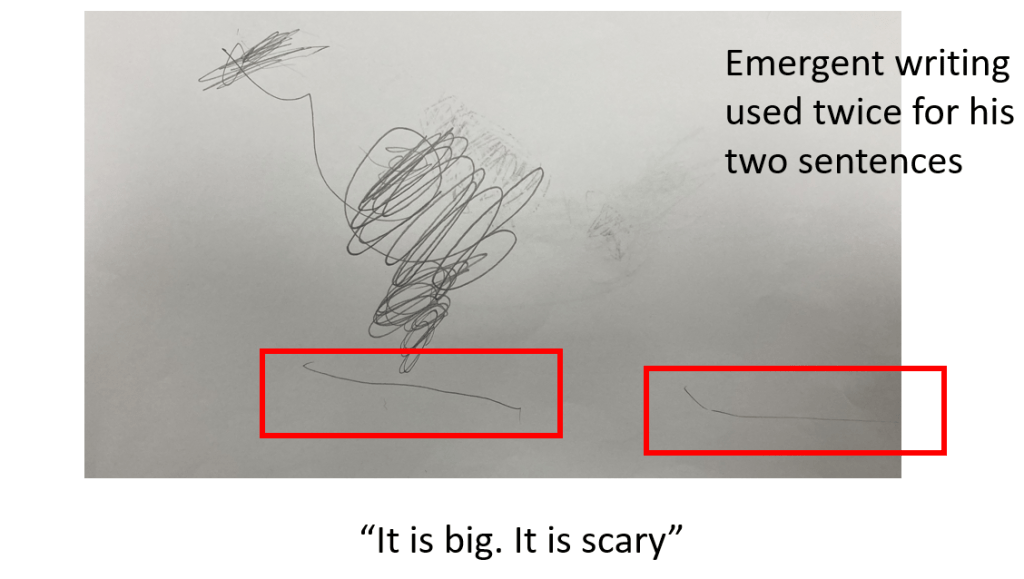

The youngest children, even before they begin to master conventional writing, convey meaning through written symbols – when given the opportunity. Take Wyatt as an example. Below is the first picturebook Wyatt ever made. Wyatt attends a school in an economically-underserved area of Leeds. Wyatt produced this book on his first week at Nursery.

Isn’t that a brilliant story? I should explain that Wyatt is already learning a number of things about writing. He is learning that a book should have a picture and some emergent writing on every page. He has also learnt that when you are ‘telling’ your book – you should ‘tickle your writing’. This involves moving your finger across your emergent writing so you can tell people what it says (oral language development anyone?).

Far from being a mere precursor to conventional writing, emergent writing is seen as a foundational phase that children go through and ensures they engage with written language as a tool for communication. It’s this emergent writing that helps them understand why developing their transcription is so necessary – because it will help them make and share meaning with others more successfully.

As you can see from Wyatt’s book, the development of composition – the ability to generate ideas, organise them, and express them is a critical aspect of emergent writing. However, once letter formation and encoding instruction is introduced, children transition quickly towards using informed spelling, writing sentences, and making simple stories and information texts. Therefore, emergent writing only acts as a very temporary scaffold [LINK].

Emergent writing develops children’s communicative competence from the earliest stage of their writing development. By allowing children to express themselves, we develop children’s motivation and confidence. As a result, they want to learn more about writing and being a successful writer. Emergent writing helps children know the reason why they are being apprenticed in transcription. This leads nicely into our next section…

The Importance Of Transcription In Early Writing Development

As you can see in the table shared earlier, emergent writing does not dismiss the importance of transcription skills. Transcription is, in fact, a necessary foundation for successful composition.

The work of Berninger & Amtmann (2003), among others, highlights the cognitive demands involved in writing. Transcription, particularly when children are first learning to write, requires a lot of cognitive effort. Our young writers must focus on letter formation, encoding, and punctuation while simultaneously thinking about their writing ideas.

Berninger & Amtmann simply wanted to remind us that during this early stage in their writerly lives, children might not always fully engage with the content of their ideas or the organisation of their writing. But over time, with repeated practice, and with explicit instruction in handwriting and encoding, this gets better and better. It’s important to note that, according to Berninger & Amtmann, transcription does not need to be mastered before composition can take place. Instead, research recommends developing both concurrently but with a particular focus on transcription [LINK].

An Evidence-based Centralist Approach

Given the intertwined nature of transcription and composition, a centralist approach to early writing instruction is essential. Instead of strictly separating transcription and composition, or focusing exclusively on one at the expense of the other, teachers should aim to provide an approach that supports both aspects of writing in tandem. The balance lies in prioritising transcription without excluding opportunities for meaningful composition. This centralist approach acknowledges that:

1. Transcription supports composition: Secure transcription skills serve as a foundation for more complex writing projects [LINK]. When children are able to write without excessive effort spent on forming letters or encoding words, they have more cognitive resources available to focus on their ideas and revising their manuscripts. Teachers will see that as children’s transcription improves – so their compositions improve too.

2. Composition supports transcription: It’s important to remember that dictation isn’t writing. Writing is about expressing ideas and communicating meaning [LINK]. By engaging in composition from an early age, children actually understand the purpose behind learning about transcription. Writing is a tool for communication – not the nonsensical forming of letters and the encoding of sounds for no apparent reason (dictation). Early compositional opportunities ensure children are always using and applying their newly acquired transcriptional skills [LINK].

3. Early writing experiences foster motivation: Children who are encouraged to write stories, draw, and share ideas through writing, even while their spelling and handwriting is still developing, are more likely to have a positive attitude towards being a writer [LINK]. This motivation is the fuel that supports children’s engagement with writing, leading to greater proficiency in both transcription and composition over time.

Practical Implications For Instruction

A centralist approach to early writing development can be implemented by utilising several key instructional strategies:

1.Explicit Handwriting Instruction & Practice

The research is clear [LINK]. Children benefit from explicit handwriting instruction and practice. The more this becomes automated, the more cognitive space children have to focus on the compositional aspects of their writing.

2. Explicit Encoding Instruction & Practice

Again, the research is clear [LINK]. Children benefit from explicit encoding instruction and practice. This involves teachers modelling strategies for encoding the words you want to transcribe to paper (or screen) before inviting children to use these strategies for themselves during writing time [LINK]. The more this becomes automated, the more cognitive space children have to focus on the compositional aspects of their writing.

3. Integrated Writing Activities: Teachers can design simple writing projects that allow children to engage in both transcription and composition. For example, children can be encouraged to write simple stories, make little information books, draw pictures and share what their writing says orally [LINK and LINK]. As children continue to develop fluency in their transcription, the focus can shift towards revising their compositions, expanding ideas, and using more complex sentence structures [LINK].

4. Realistic Expectations: Writing development covers the lifespan [LINK]. In the earliest stages of writing development, we should be flexible in our expectations for transcriptional accuracy. While basic transcription skills should be developed as a matter of priority, children should also be encouraged to experiment with writing in ways that offer them opportunities for idea generation and meaning-making. Informed spelling, irregular letter formation, and incomplete sentences should not be seen as sinful and unforgivable errors but part and parcel of the natural progression towards producing more refined writing. After all, these are young apprentice writers we are talking about!

5. Providing Instruction & Feedback On Both Aspects: Educators can provide instruction and feedback that supports both transcription and composition. For example, they might praise a child’s creative ideas during Author’s Chair, offer feedback to children’s encoding attempts, and provide corrections during handwriting practice. Feedback should be supportive and encouraging, helping children understand the value of both accurate transcription and meaningful composition [LINK].

6. Encouraging Writing Across Contexts: Writing should not be confined to dictation sessions, handwriting practice and formal writing lessons. Encouraging children to write during continuous provision and in response to their reading during reading lessons in important too. Continuous provision is an excellent way of providing additional authentic opportunities for both transcription and composition to develop simultaneously.

7. Focus On Developing Children’s Writing Fluency. Writing fluency refers to a child’s ability to write quickly, smoothly, and happily without frequent pauses to think about letter formation or spelling. It can be measured by either the amount written within a certain time or the frequency of pauses during writing. Skilled writers tend to write longer sections without pausing, which reflects their ease in translating thoughts into words. Factors like spelling, handwriting speed, working memory, attention, and motivation all influence writing fluency. Enhancing these skills can help children express their ideas more easily and improve the quality of their writing overall [LINK].

Conclusion

The development of writing skills in young children is a dynamic process that requires a focus on both transcription and composition. By integrating emergent writing with specific attention on foundational transcription skills, we can create a writing pedagogy that fosters both creative expression and technical proficiency. This approach ensures that children have the opportunity to engage meaningfully with writing (and being a writer) from the earliest stages, while gradually developing the skills needed to express themselves more fluently and effectively. In doing so, we empower young writers to develop the cognitive, affective, motor, and linguistic skills necessary for success.

Recommended publications:

- Getting Children Up & Running As Writers by Ross Young & Felicity Ferguson [LINK]

- Already Ready: Nurturing Writers in Preschool and Kindergarten by Katie Wood Ray & Matt Glover [LINK]

- Kid Writing: A Systematic Approach to Phonics, Journals, and Writing Workshop by Eileen Feldgus & Isabell Cardonick [LINK]

- What Changes In Writing Can I See? by Marie Clay [LINK]

- Handbook On The Science of Early Literacy by Sonia Cabell, Susan Neuman, and Nicole Patton Terry [LINK]

Recommended articles:

- How do children start learning to write before they start school? [LINK]

- How can you teach children to write before they know their letters? [LINK]

- Let’s use ‘kids writing!’ [LINK]

- Encoding and ‘informed spellings’ [LINK]

- Promoting preschoolers’ emergent writing [LINK]

- The unrealised promise of emergent writing: Reimagining the way forward for early writing instruction [LINK]

- The effects of preschool writing instruction on children’s literacy skills [LINK]

- Early alphabet instruction [LINK]

- Early spelling development [LINK]

- What are children doing as they produce writing? [LINK]

- How do we develop writing fluency? [LINK]

- What is writing fluency? [LINK]

- Spelling and handwriting provision: A checklist [LINK]

- Building up to extended writing projects [LINK]