By Jean Marie Farrow, Barbara A. Wasik, Annemarie H. Hindman and Michael J. Farrow

Original article: LINK

Supporting early writing development is essential for children’s future literacy and academic success. While many early childhood classrooms offer writing centres with paper and writing tools, teachers often miss opportunities to provide intentional support for key writing skills. Specifically, there is a lack of focus on the language-based skills needed to help children generate and translate their ideas into writing [LINK]. Instead, writing instruction in early childhood typically emphasises isolated skills like name writing, letter formation, and encoding. While these activities support children’s transcriptional development, they do not support children’s compositional development, which is crucial for children’s long-term academic success [LINK].

When children are not given opportunities to compose their own writing – they can struggle as they move through school and writing projects become more demanding [LINK]. It can often be a lack of compositional development which leads to children’s frustration and avoidance for writing and prevents them from discovering the pleasures of expressing their thoughts, knowledge and creativity (Young in press).

By developing children’s compositional skills early on, teachers can help students build both the skills and confidence they need to write effectively. This paper provides practical strategies from successful early childhood classrooms that teachers use to reduce children’s cognitive load and improve their development during writing time.

***

Isolated skill practice in letter formation and encoding, while essential, is not enough to provide a well-rounded writerly apprenticeship [LINK]. Composing involves multiple cognitive steps, beginning with idea generation. For example, a teacher might ask, “What could the story books we are making be about?” This question encourages children to generate ideas with a clear goal in mind. They then translate those ideas into drawings and language, using their vocabulary, grammar, and understanding of conversations. Finally, children transcribe their ideas onto the paper in developmentally appropriate ways — whether through emergent writing or conventional adult writing [LINK].

It’s this translation of thoughts into written form that propels children’s writerly growth [LINK]. It’s these sorts of opportunities which draw children’s attention to the magic of writing – and how you can use it to make and share meaning with others. They begin to understand that writing is a means of expressing yourself – and it’s fun! When teachers intentionally support this process, they help students not only improve their writing skills but also cultivate a deeper connection with them as people [LINK].

If children are given a well-rounded writerly apprenticeship in the early years, we typically see them go through the following milestones:

- Ages 2 – 5: Children translate their ideas for their writing into short phrases. For example, “Pirate ship crashes. BOOM!”.

- Ages 4-6: Children begin using sentences, including the use of modifiers and more precise vocabulary. For example, “The pirate ship is on the ocean”.

- Ages 5-7: Children often verbalise multiple sentences, using their growing understanding of grammar to tranlsate their ideas for writing. Their ability to use the correct verb tenses improves. For instance, “There was a terrible storm. The pirates were jumping overboard! Ahhh!” Here, the child not only shifts focus between the storm and the pirates but also shows an emerging ability to handle tense changes.

At this stage, children’s sentence structures can move away from being relatively simple to expressing more intricate ideas by combining ideas through compound and complex sentences [LINK].

***

Research has consistently shown that writing stories, expressing opinions, and creating informational texts – activities that demand children to compose writing – contribute far more to children’s writing achievement than isolated skill practice like spelling drills or handwriting exercises [LINK, LINK, LINK]. In other words, it’s through writing their own stories and ideas that children become better writers. This type of generative practice also strengthens their oral language and listening comprehension, reading, vocabulary, sentence structure, and overall literacy skills too. Classroom environments that foster interactive and supportive writing activities, where teachers engage with students about their topics, structure, and language choices, can lead to higher-quality writing [LINK, LINK].

***

Despite its importance, many early years teachers can feel underprepared to provide effective writing instruction. Writing in the early years does requires direct and intentional teaching (Young & Ferguson 2023, 2024a, 2024b).

Practical strategies for fostering idea generation and compositional development

Below are the sorts of effective strategies that teachers in high language-growth classrooms employ to support their children’s writing development.

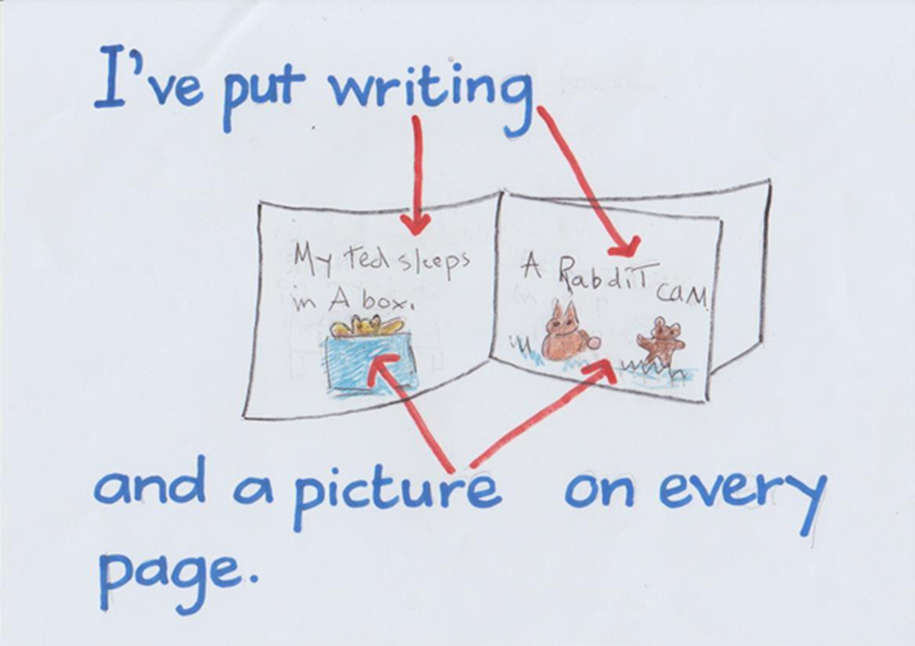

- One effective way to help children generate ideas is by focusing on their memory retrieval. Start by reminding them of the writing project and its purpose. For example, if the project is making their own ABC Book, show them an example. This narrows their attention and directs their memory to retrieve relevant information about the ABC books they’ve read previous – for example, they have a picture and a word on every page.

- Expand children’s ideas by repeating what they said as a question. Expansions are a great way to help children build on their initial ideas. For example, if a child says, “My parrot went to bed,” you might respond, “Your parrot went to bed?” “Yes, it goes right into his cage and daddy puts a blanket over it – night night.” “Whoa, cool. Let’s definitely write that down!” Expansions like this extend children’s thinking and help them construct more detailed pieces of writing than they would otherwise [LINK].

- For classrooms with a high proportion of bilingual learners, these strategies can be especially useful, as English language learners may need extra support in memory retrieval and language construction. For more details, see our eBook: A Teacher’s Guide To Writing With Multilingual Children [LINK].

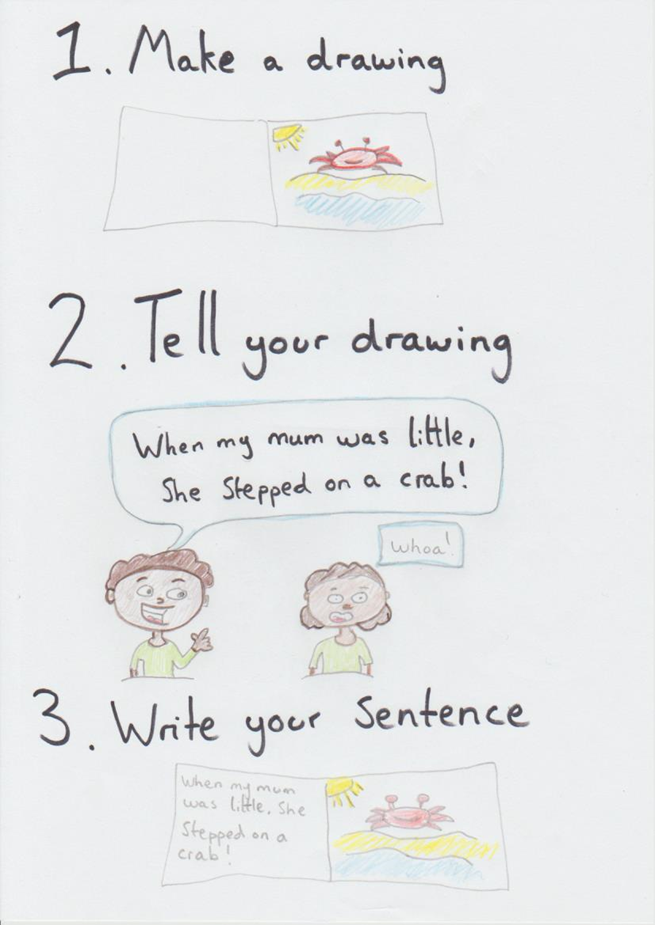

- Use a developmentally appropriate writing process where children are encouraged to talk, draw and talk about their drawings before writing about what their drawing ‘says’. Once their writing is finished they should share what they’ve made with others [LINK].