Because of formatting, we can recommend downloading the PDF version of this article:

The DfE’s interim curriculum and assessment review report suggests a potential shift away from teacher-assessed writing towards a ‘writing fluency’ test.

“We have… heard concerns that the writing assessment at the end of Key Stage 2 does not validly assess pupils’ ability to write fluently” (p. 39)

“Pupils… spend considerable classroom time learning to reproduce writing containing textual features to meet writing assessment criteria, rather than developing fluency in writing. Therefore, in the next stage of our work, we will examine how the assessment of writing at key stage 2 can be improved”. (p.39)

What is writing fluency?

In our article Visualising The Science Of Writing: The Writing Map Explained [LINK] we define writing fluency as the ability to smoothly, happily, and quickly translate thoughts into written words. It encompasses the seamless integration of various skills, including:

- Transcription skills: Proficiency in handwriting and spelling, enabling effortless transcription of ideas.

- Composition skills: The capacity to generate and organise ideas effectively, constructing coherent and meaningful text.

- Cognitive skills: Functions such as working memory and attention that support the writing process.

Developing children’s writing fluency is a crucial part of writing development, as it allows children to focus more on the content and quality of their writing rather than the mechanics of transcription, leading to more expressive and effective communication. Writing fluency is also a key skill for success in both academic and professional contexts. In today’s fast-paced world, being able to write quickly, clearly, and coherently is essential.

A high-stakes national ‘writing fluency’ assessment would likely be designed to measure students’ ability to write quickly, coherently, and effectively across different prompts and genres. It would need to balance validity (ensuring it assesses actual writing fluency) with reliability (ensuring consistent scoring across students and schools). Key features might include:

Assessment structure

- Dictation task: Students would be required to transcribe a dictated passage.

- Timed writing tasks: Students would be required to produce short and extended responses under time constraints (e.g. 10-minute, 30-minute, and 60-minute tasks).

- Multiple writing modes: The test would assess fluency in different writing styles, such as:

- Narrative (story writing or personal narratives)

- Expository (explanatory or informational writing)

- Argumentative/persuasive (making a case using evidence)

Scoring metrics

- Accuracy in transcribing dictated sentences.

- Words per Minute (WPM) and output volume: While not the sole measure, writing fluency often correlates with the ability to produce coherent texts quickly.

- Coherence and organisation: Does the writing follow a logical structure with clear transitions?

- Sentence variety and complexity: Assessing whether students use a mix of sentence structures effectively.

- Grammar and mechanics: While fluency won’t always mean the perfect use of conventions, consistent errors will be seen to hinder readability and would be flagged.

- Responsiveness to prompt: Does the writing stay on topic and address the assigned task?

A rubric would account for both quantitative fluency (how much a student writes and how fast) and qualitative fluency (how well the writing is structured and how clear it is). Here’s an example of the sort of thing we would expect:

- Total score: Out of 100 points

- Weighted scoring: Certain categories (e.g. volume and coherence) could be weighted more heavily than others.

AI-assisted marking

Scan-to-score technology will be used to digitise the children’s writing. An AI-powered tool would then provide an automated score based on syntax, coherence, and fluency. Human markers might only be used to review ‘edge cases’.

Implementation logistics

Ensuring fair and efficient administration of the test across a national level would require clear policies for timing, administration, technology, accommodations, and grading. Here’s an example of what a test format and timings could look like:

- Test duration: 60–90 minutes total, including multiple timed prompts:

- Dictation task (2-5 mins): Measure accuracy of spelling, punctuation and capitalisation.

- Quick writes (5–10 mins): Measure raw fluency (words per minute, coherence under pressure).

- Extended response (30–40 mins): Measure depth, organisation, and complexity of sentences.

- Rotating prompts: To prevent over-preparation, the test would draw from a database of prompts that cover:

- Narrative fluency: E.g. “Describe a time you overcame a challenge.”

- Expository fluency: E.g. “Explain how phones have changed communication.”

- Persuasive fluency: E.g. “Should schools have later start times? Support your opinion.”

- For students with disabilities: Speech-to-text, extended time, scribes for profound handwriting limitations.

Mock sample and alignment with the National Curriculum in England

A national writing fluency assessment in England would need to align with the National Curriculum (NC) for English, ensuring that it measures key competencies expected at different key stages. Below, I provide a mock sample of what such a test could look like, followed by an analysis of how it would align with the NC in England.

These prompts would be designed to assess writing fluency, focusing on timed responses that measure a student’s ability to generate ideas quickly, organise thoughts, and write coherently under strict time constraints.

| A Writing Fluency Test This assessment consists of three sections: A. Dictation – 1-5 minutes B. Quick Writes (Short Timed Tasks) – 5-10 Minutes C. Extended Writing Tasks – 20-30 Minutes The prompts are age-appropriate and gradually increase in difficulty between KS1 (ages 5-7) and KS2 (ages 7-11). A. Dictation (1-5 minutes) KS1 (ages 5-7) Instructions: You will hear a short sentence. Listen carefully and write down exactly what you hear. Pay attention to spelling, punctuation, and capitalization. You will have 1 minute to write the sentence. Dictation Sentence: “The dog ran fast in the park.” Evaluation Criteria: Spelling: Correct spelling of common words like dog, ran, fast, and park. Punctuation: Capitalisation of the first letter and a fullstop at the end. Handwriting: Legible handwriting with proper spacing and size. Accuracy: Accurate transcription without errors or omissions. KS2 (ages 7-11) Dictation Passage: “At the top of the mountain, the view was incredible. The sky was clear, and the sun shone brightly over the village below. Gary could see the river winding through the trees, and they felt proud of their long journey.” Evaluation Criteria: Spelling: Accurate spelling of words like mountain, incredible, winding, and journey. Punctuation: Correct use of commas, fullstops, and capitalisation of the first letter of the sentence and proper nouns. Handwriting: Clear handwriting with well-formed letters and consistent spacing. Accuracy: Proper transcription of the passage, ensuring no missing words or changes to the sentence structure. B. Quick writes (5-10 Minutes) These short tasks are looking for fast idea generation and coherent sentence construction. KS1 (ages 5-7) Descriptive writing: “Describe your favourite toy. What does it look like? How does it feel? Narrative writing: “Write about a time you felt really happy. What happened? Persuasive writing: “Should we have a longer playtime? Write one reason why.” KS2 (ages 7-11) Descriptive writing: “Imagine you are walking through a spooky forest. Describe what you see and hear.” Narrative Writing: “Write the beginning of a story about a child who finds a mysterious key.” Persuasive Writing: “Should homework be banned? Write two reasons for your opinion.” C. Extended writing tasks (20-30 Minutes) These would look to assess depth, structure, and sustained fluency. KS1 (ages 5-7) Story writing: “Write a story about a lost animal trying to find its way home.” Diary Entry: “Write a diary entry about your best day ever. What did you do?” Non-Fiction Writing: “Write instructions for how to brush your teeth.” KS2 (ages 7-11) Story writing: “A spaceship has landed in your school playground. Write a story about what happens next.” Persuasive letter: “Write a letter to your headteacher asking for a school pet. Give three reasons why it would be a good idea.” Explanation writing: “Explain how the water cycle works.” |

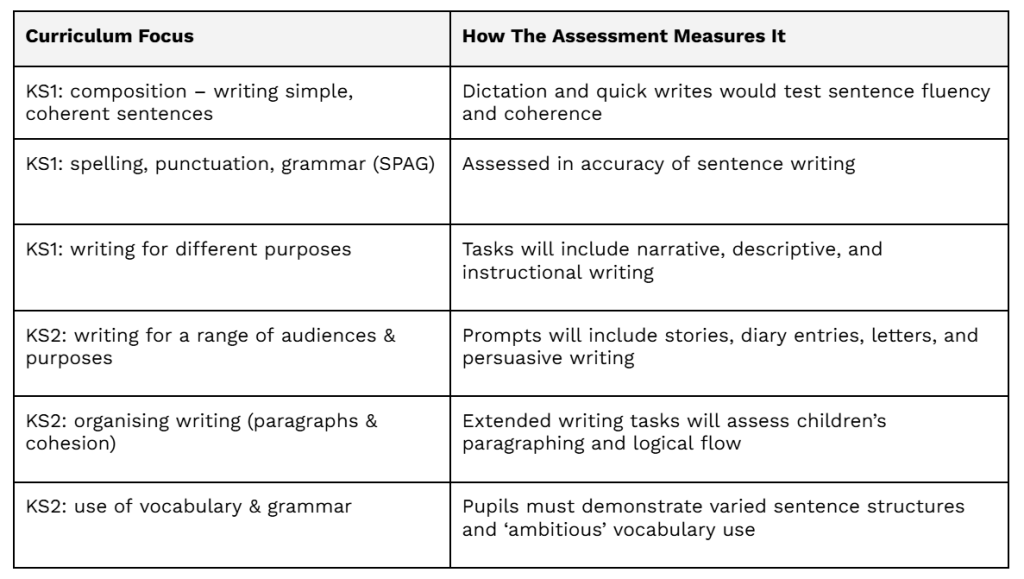

Alignment with the National Curriculum for England

This type of assessment would align directly with KS1 and KS2 National Curriculum writing objectives.

How such an assessment would be used in schools

- Formative tool: Educational publishers will capitalise on the high-stakes nature of the fluency test to produce practice papers. Schools will continually use these to identify writing gaps throughout children’s time at primary school.

- Summative benchmark: Will be administered at the end of KS1 to measure progress. Low-scoring students will receive interventions and even more test practice than their peers.

Why is a high-stakes national ‘writing fluency’ test a bad idea?

Informal handwriting, spelling and compositional fluency tests can be useful as a diagnostic tool for teachers and SENCOS (see LINK and our book Supporting Children With SEND To Be Great Writers for more details). However, the potential implementation of a high-stakes national ‘writing fluency’ accountability assessment is fraught with significant pedagogical and ethical concerns. Such an approach not only undermines the intricate nature of the writing process (see the EEF’S writing guidance for more) but also imposes detrimental effects on both teachers and children.

A complete misunderstanding of the writing process

Writing is inherently a recursive and social activity, encompassing stages of idea generation, talking, drawing, planning, drafting, revising, proof-reading and publishing and performance. A writing fluency test, however, would reduce writing to a high-stake-one-time-perfect-product event, flying in the face of the actual processes writers engage in. You can’t just ignore the natural messiness and unpredictability of writing. This reductionist view would fail to capture the depth of a student’s writing abilities and would promote an utterly superficial understanding of writing as being merely product-oriented.

Questionable validity and reliability

The validity of such assessments is contentious. A single test cannot encompass the diverse genres, audiences, and purposes that writing entails. Moreover, reliability is compromised as student performance can fluctuate due to factors unrelated to their writing proficiency, such as emotional maturity, test anxiety or unfamiliarity with the content of a writing prompt. This variability questions the consistency and fairness of the assessment outcomes. To put it bluntly, the only thing we will truly learn from a fluency writing test is which children are good at taking fluency writing tests.

Narrowing of curriculum and instruction

As you can see in the example shared above, high-stakes testing often leads to a narrowed curriculum, where teaching is geared predominantly towards test preparation. Teaching to the test will limit students’ exposure to a rich and varied writerly apprenticeship. Consequently, students will leave primary school adept at producing formulaic responses at the expense of developing genuine writing skills.

Negative impact on student motivation and well-being

The pressure associated with high-stakes assessments can adversely affect student motivation and well-being. The emphasis on performance over learning can foster a fear of failure and an aversion to taking authorial risks. A high-stakes fluency test will undoubtedly diminish students’ intrinsic interest in writing. Such a learning environment will be counterproductive to cultivating a lifelong appreciation for writing and being a writer. Children might develop a sense of academic competency (if they are lucky) but there will be little chance of feeling a sense of personal satisfaction or social connection from writing and being a writer.

By equating writing success with speed, fluency tests create a culture where students feel pressured to produce words rapidly, rather than thoughtfully. Many students, especially those who are neurodivergent, multilingual, or reflective writers, may internalise the belief that they are ‘bad writers’ simply because they do not write quickly and under artificial conditions. This will make writing a source of anxiety rather than enjoyment.

Writing fluency tests ignore how great writers actually write

If good writing was only about speed, some of the greatest writers in history would have failed. Professional writers frequently sit, revise, and agonise over their words – the very opposite of what a fluency test would demand. Here’s what famous writers have said about their writing process:

| I write one page of masterpiece to ninety-one pages of s*** – Ernest Hemingway Writing fluency tests don’t allow time for revision – the part of writing that Hemingway saw as crucial There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed. – Ernest Hemingway Genuine writing is often slow, not something done at speed in a test setting I’m not a very fluent writer. I have to think about every sentence – J.K. Rowling Rowling, a globally successful author, explicitly states she is not a ‘fluent’ type of writer Easy reading is damn hard writing – Nathaniel Hawthorne A piece of writing may read fluently, but that doesn’t mean it was quickly or effortlessly written Writing is easy. All you have to do is cross out the wrong words. – Mark Twain A witty reminder that writing is as much about revision as it is about initial fluency A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people. – Thomas Mann Great writers don’t necessarily find writing effortless – on the contrary, they struggle with it more than most The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter – Mark Twain Good writing is about precision and careful word choice, not always speed |

These insights highlight that true writing excellence is not about speed or instant fluency – it is about thought, time, revision, and perseverance. If even the most celebrated authors wouldn’t meet the expectations of a fluency test, how can we justify imposing such unrealistic standards on children?

Inadequate reflection of diverse student populations

Writing tests, by their very nature, are unable to account for the diverse backgrounds and experiences of students. Cultural biases in writing prompts will disadvantage students who are unlucky not to align with the content knowledge required to write successfully to the prompt. We see the exact same thing with reading tests. Alternatively, students who favour a writing process where they plan extensively, or revise with care and attention, may be incorrectly labelled as ‘weak’ writers. This lack of inclusivity undermines the principle of fairness in assessment.

Constraints on teacher professionalism

Teachers know full well that they will be asked to do what needs to be done in terms of writing instruction and activity in order to produce good scores. I have no problem with this in principle, and indeed it can be the strength of any assessment system, but will a fluency writing test encourage good writing instruction and activity? I have my doubts. Instead, teachers will prioritise test preparation over evidence-informed writing instruction (see our article: The Writing Map & Evidence-Informed Writing Teaching for more details). With stopwatches at the ready, writing will become a heartless and thankless task – one that neither teachers nor students will find meaningful.

Conclusion

The potential adoption of a high-stakes national ‘writing fluency’ assessment would be a step backwards. It’s a misguided approach that overlooks the complexities of writing and the diverse needs of young writers. It would disregard the realities of how great writers actually write and instead punish students who don’t fit a rigid, outdated model of ‘good writing’. A more effective strategy lies in empowering teachers to implement formative and process-based summative assessments. Such assessments would honour the multifaceted nature of writing and being a writer.