‘We can’t give children rich lives, but we can give them the lens to appreciate the richness that is already there’ – Lucy Calkins

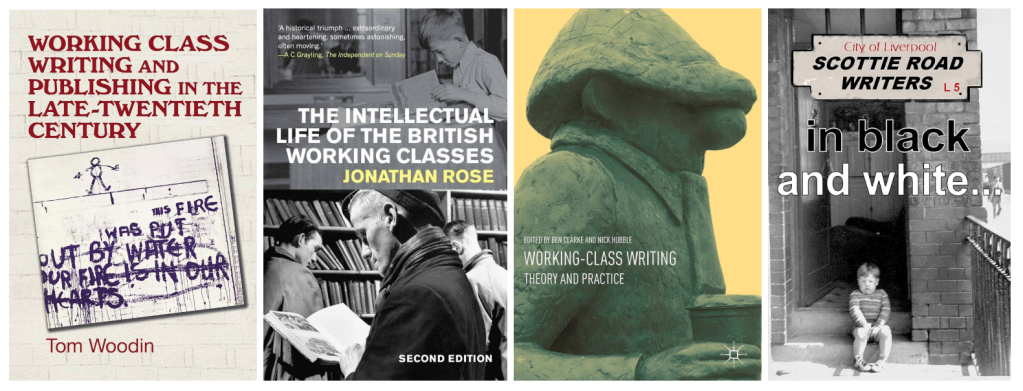

The writing lives of working-class children offer a rich tapestry of creativity, joy, humour, resilience, and empowerment. This country has a rich and enduring tradition of working-class writing. A number of books have been written on the subject. For example: Working-Class Writing & Publishing by Tom Woodin, The Intellectual Life Of The British Working Classes by Jonathan Rose and Working-Class Writing by Ben Clarke & Nick Hubble. You also have organisations like The Scottie Road Writers and Writing On The Wall in Liverpool, QueenSpark in Brighton, and The Falkland Summer School in Glasgow.

There are a number of successful writers who draw on their working-class roots. For example:

Frank Cottrell-Boyce: Our current children’s laureate, born in Liverpool to a working-class family, Cottrell-Boyce often draws on his roots in his work. His stories often highlight themes of community and resilience, as seen in Millions and his screenwriting work.

Caroline Aherne: Born in Manchester to Irish immigrant parents, Aherne grew up in a working-class family on a council estate. Her work (The Royle Family) is a celebrated portrayal of working-class family life, capturing its humour and challenges authentically.

Michaela Coel: Raised in East London in a Ghanaian working-class family, Coel’s mother worked multiple jobs to support her children. Her work (Chewing Gum, I May Destroy You) often reflects her personal experiences growing up in a working-class environment.

Lemn Sissay: Sissay was born in Wigan and placed into foster care at birth, growing up in the care system. This profoundly shaped his perspective and creative output. His poetry and plays often address themes of identity, marginalisation, and the struggles of working-class and underrepresented voices.

Katriona O’Sullivan: Raised in poverty and addiction in Ireland, she overcame significant challenges to become a senior lecturer at Maynooth University. Her memoir, Poor, chronicles her journey from deprivation to academic success. A powerful advocate for educational equity, her work inspires and empowers marginalised communities to overcome barriers and achieve their potential.

Irvine Welsh: Raised in the working-class neighborhood of Leith, Edinburgh, Welsh left school early and worked various manual jobs before becoming a writer. His novels, such as Trainspotting, vividly portray working-class lives.

Noel Gallagher: Raised in Burnage, Manchester, Gallagher grew up in a working-class Irish family. His father was a builder, and his childhood was marked by poverty and domestic challenges. His upbringing inspired many of Oasis’s lyrics, which often resonate with working-class themes.

Shane Meadows: Known for This Is England, Meadows grew up in a working-class community in Staffordshire. His films often portray working-class life.

Benjamin Zephaniah: A poet and novelist from Birmingham, Zephaniah grew up in a working-class, Caribbean family. His work addresses race, class, and social justice.

Barry Hines: Known for A Kestrel For A Knave (adapted into the film Kes), Hines was from a mining family in Yorkshire. His work often depicted working-class life.

David Almond: Raised in Felling, Tyne and Wear, Almond grew up in a working-class family in a small industrial town. His novels (Skellig) often touch on themes of imagination and transcendence, rooted in the ordinary and working-class settings.

Alan Bennett: Born in Leeds, Bennett grew up in a modest, working-class family; his father was a butcher, and his mother was a housewife. His working-class upbringing often informs his work, which is characterised by subtle humour and reflections on ordinary everyday life (Talking Heads, The History Boys).

Maurice Sendak: While not from the UK, Sendak is one of the finest ever children’s authors so we hope you’ll forgive us from his inclusion. Sendak grew up in Brooklyn, New York, to Polish-Jewish immigrant parents. His childhood was shaped by the Great Depression. As a sickly child, he spent most of his time indoors. Sendak’s work captures the inner world of childhood. He explores universal themes of anger, fear, imagination and emotional complexity.

All these writers believe they have something valuable to say and that they themselves are of value. In the process, they share their cultural capital with others. In an educational context, we have writing teachers and researchers whose work has profoundly influenced the working-class communities they look to serve. By celebrating diverse voices, they ensure that children from all backgrounds see their lives as worthy of literary exploration. For example:

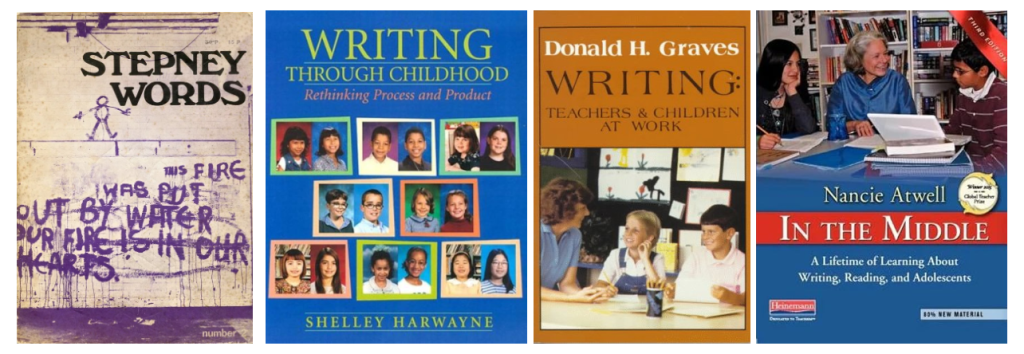

- Chris Searle: Known for his work in the 1970s encouraging working-class students in Stepney to write about their lives, leading to the publication of Stepney Words. His approach highlights the transformative potential of writing for economically underserved students. There is a wonderful documentary made about his work: LINK

- Gerald Gregory: Showed how working-class publishing can offer valuable insights for teachers, emphasising creativity, inclusion, and self-representation. By nurturing working-class children’s writing voices, teachers can challenge traditional educational practices that marginalise local experiences and culture(s). Writing, often seen as daunting for these children, instead becomes transformative and empowering. Publication: Community-Published Working-Class Writing In Context In Changing English.

- Harold Rosen: Highlighted how dangerous it is to believe that working-class children are culturally deprived or that their lives are arid (lacking in interest or meaning). At the same time, he rightly pointed out that we shouldn’t generalise, stereotype, fetishise or romanticise their experiences either. Publication: Harold Rosen – Writings On Life, Language & Learning.

- Shelley Harwayne: Her work in New York City public schools focuses on developing writing among economically underserved urban communities through real-world connections to literature and writing. For Harwayne, the act of writing allows working-class children to see their lives reflected and valued, challenging societal norms that often dismiss their experiences. Publication: Writing Through Childhood.

- Donald Graves & Nancie Atwell: Both emphasise collaborative approaches to writing instruction, often working in rural and underfunded schools. Publications: Graves – Writing: Teachers & Children At Work and Atwell – In the Middle: New Understandings About Writing, Reading, and Learning.

- Anne Haas Dyson: A seminal educational researcher who studies how children from diverse backgrounds can engage productively with writing in school. Publication: Writing The School House Blues and Rewriting The Basics: Literacy Learning In Children’s Cultures.

- Tom Newkirk: Focuses on writing as an avenue for self-expression, especially for male students in rural, working-class areas. Publication: Misreading Masculinity: Boys, Literacy & Popular Culture.

- Melanie Meehan & Kelsey Sorum: Educators who advocate for equitable literacy practices. They are passionate about empowering marginalised students. Through their work, they inspire teachers and students alike to embrace writing as a tool for self-expression, fostering confidence and critical thinking in diverse classrooms. Publication: The Responsive Writing Teacher.

- Django Paris, H. Samy Alim, Celia Genishi, and Donna Alvermann: Influential educators advancing equity in writing teaching. Through their collaborative work on culturally sustaining pedagogies, they provide insights and strategies for inclusive writing classrooms, empowering teachers to celebrate and elevate diverse student voices. Publication: Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies.

- Tasha Laman, Amy Flint, and Teresa Fisher: Their work focuses on equitable writing teaching for English language learners in economically underserved areas. By supporting children’s writing voices, and celebrating their diversity of language, they inspire teachers to create empowering classrooms where all young writers can thrive. Publication: From Ideas to Words: Writing Strategies for English Language Learners.

- Mariana Souto-Manning: A renowned educator and advocate for equity in early childhood education. Her work focuses on culturally responsive teaching. Publication: Reading, Writing, And Talk: Inclusive Teaching Strategies For Diverse Learners.

- Ross Young, Felicity Ferguson, Doug Kaufman, and Navan Govender: Advocates for transformative writing instruction. Through their Writing Realities work, they champion creative, writer-centered approaches that foster self-expression and inclusivity. Their commitment to empowering all students as writers helps to cultivate confidence, competency, and a lifelong love of writing. Publication: Writing Realities.

Writing For Pleasure Teachers: The Writing For Pleasure approach works with schools in economically underserved areas to improve children’s writing and develop their writer identities. The movement is particularly focused on providing children with the highest possible expectations and an outlet for their personal expression, fostering a love of writing in the process. Students learn to write in a variety of genres and on diverse topics. Their manuscripts are often celebrated through publication and performance. Publication: Writing For Pleasure: Theory, Research & Practice.

There is surely no lower educational expectation than believing a child has nothing to say for themselves. That they are empty – devoid of any thoughts, knowledge, ideas or experiences that readers would feel worth hearing about. The writing lives of working-class children actually stand as a testament to the power of writing as a tool for self-expression, cultural preservation and relationship building. Your young writers, taught, guided and nurtured by you, can demonstrate that every voice has value and everybody’s stories and thoughts matter. By creating a school community where children’s experiences and funds-of-knowledge are celebrated and shared, you will not only empower the pupils in your care but also enrich the broader cultural narrative of your local community.

Recommended Reading:

The educators and writers highlighted in this article remind us that writing is not only an academic exercise – it is also a means of liberation, a way to bridge divides, and a lens through which children can find the richness in their own lives. As we continue to champion equity, creativity and independence in the writing classroom, let us commit to providing all our children with the tools and opportunities to find their voices, to write their truths, and to envision a life-long love affair with being a writer. Through writing, we can create a world that values what every child has to share.